Whenever there is a discussion about the future of the Yorkshire Dales, one topic is soon to come up - the plight of young working people and their families in the Dales caused by a lack of affordable housing.

The brutal truth is that the stunning landscapes and gorgeous stone villages make the Yorkshire Dales National Park a wonderful place in which to live. This means that house prices face a hefty premium. If you retire and have a three bedroom home to sell in Surrey, a Dales village is a great place to spend your retirement years. Hardly surprising an average home in the National Park is over a third more expensive than a similar house in nearby Leeds.

The National Park has a population of around 20,000 people. It also has around 12,000 houses. This suggests that there should be plenty of homes to meet local needs, even allowing for single person households.

And contrary to popular myth, new houses are constantly being built in the National Park. Between 2001 and 2011 – just ten years – around 1,000 new houses were erected or converted from barns or other existing buildings in the National Park. But the curious fact is this. The total population of the Dales only increased during the same period by 100.

So what was happening? The answer is that a high proportion of these and existing homes were being used as second homes or for holiday letting. Statistics show that in 2001 15% of houses in the Dales were second homes or holiday lets. By 2011 this figure escalated to 23%.

The simple reason for this is market forces. Investing in a property in the Dales for use as a second home or holiday let is an attractive economic proposition. But this prices out young families and people on average incomes if the cheapest properties now cost well over £200,000 in a Dales village. Most cost far more than that. Young people starting out on the property ladder, working in tourism or in agriculture, earning perhaps little more than the minimum wage, can never afford even the deposit for such a home.

In the past, young Dales families would be eligible for a local authority house at an affordable rent. Unfortunately the popular 1980s Right to Buy scheme changed all that. People living in council owned property were encouraged and indeed supported to purchase their rented home at a bargain price, which gave them a useful boost up the property ladder. Once they owned their property they could, in a few years’ time, sell it on at the best market price. That was just fine, but it meant that the next generation of young people no longer had their starter home to rent, as now no new council homes were being built. Likewise older people moving into care, would sell their home to outsiders at the highest price. Whole areas of Dales villages and market towns have what used to be called Council Houses, which are now privately owned. In the 1980s, the National Park had a pool of around 3,500 local authority homes for ordinary working families in the Dales to rent. 30 years later these properties are no longer available for rent on a permanent basis, yet ironically an almost similar number of homes are available at premium price for holiday rents or second home holiday use.

So what is the answer? The National Park Authority has set itself the target of ensuring at least 30 so-called affordable homes are built in the larger settlements in the Dales per year.

But much more drastic action is needed, which would cut totally against current political dogma supported by all parties. There could be a clear ban on building any more houses in the Dales except for renting at realistically affordable levels to people with jobs or strong links to the area. There could be a ban on all existing homes registered as primary dwellings being converted to holiday lets. There could be draconian property taxes on second homes at a level that encouraged owners to release them for first homes.

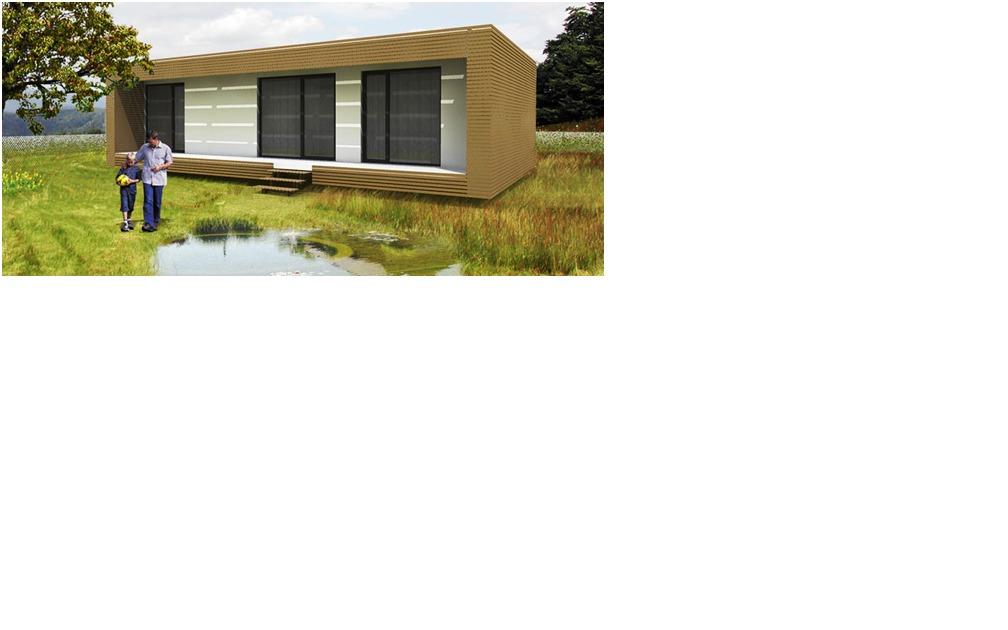

A further radical step might be to no longer require new houses to imitate 19th century stone cottages, encouraging modern prefabricated building methods to cut costs. These need not be the ugly asbestos “pre-fabs” used as emergency housing in the 1950s. In Germany, architects have designed “passive houses”, timber framed, carbon neutral maisonettes, superbly insulated with minimal heating energy requirements, designed to be visually unobtrusive. Even within larger settlements the National Park as well as peripheral towns and villages, close to key services such as schools, shops, buses, doctor’s surgeries, there are areas where a dozen or so well designed cabins could be carefully sited and screened without dramatically changing the character of the area. This is tolerated for agricultural buildings or light industrial estates, so why not homes?

Sadly the truth is politicians are willing to shed crocodile tears for the plight of young people in the Dales but not to act. Tears come cheap. Strategies and policies change nothing if not implemented and funded. What is needed is a radical commitment from our local politicians to get something done, even if it requires the tearing up of outdated ideologies and political shibboleths, to interfere in what is chronic market failure in terms of meeting the urgent needs of Dales communities.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here