MY Skipton upbringing was during the last great flourish of northern milldom. Yet whichever way I looked I saw a horizon crowned by the heathery spurs of the Pennines. The town, the mills and the terraced housing had a glorious setting.

Born in 1928, I grew up in Skipton through the lean years of the 1930s. An ancient town had been transformed by industry, represented by smoking mills. The sky, and sometimes the streets, were filled with acrid smoke as the fires in mill boilers, which had been lazing during the night, hissing with barely suppressed energy, were raked and replenished.

At times the mini-forest of chimneys poured so much smoke into the air, it was said – tongue in cheek – the crows had to fly backwards to keep the soot out of their eyes.

Each morning, as the eastern sky pearled with the coming of daylight, mill workers were roused by the clangour of alarm clocks.

In earlier times, a knocker-up, carrying a long rod, had made his rounds, rapping on bedroom windows and pausing briefly until his presence was acknowledged by a bog-eyed worker who had just scrambled out of bed. Each evening, during the darker months of the year, the lamp-lighter went on his rounds.

I had many glimpses into working mills. If a door had been left open, an outward rush of air was warm, sweet-smelling – cottony, indeed. I sometimes glanced into a work area where women stood by the side of chattering looms, lip-reading. It was a process known as mee-mowing. The saw-shaped roof of a mill shed had north lights, so positioned that direct sunlight did not fall on the work in hand.

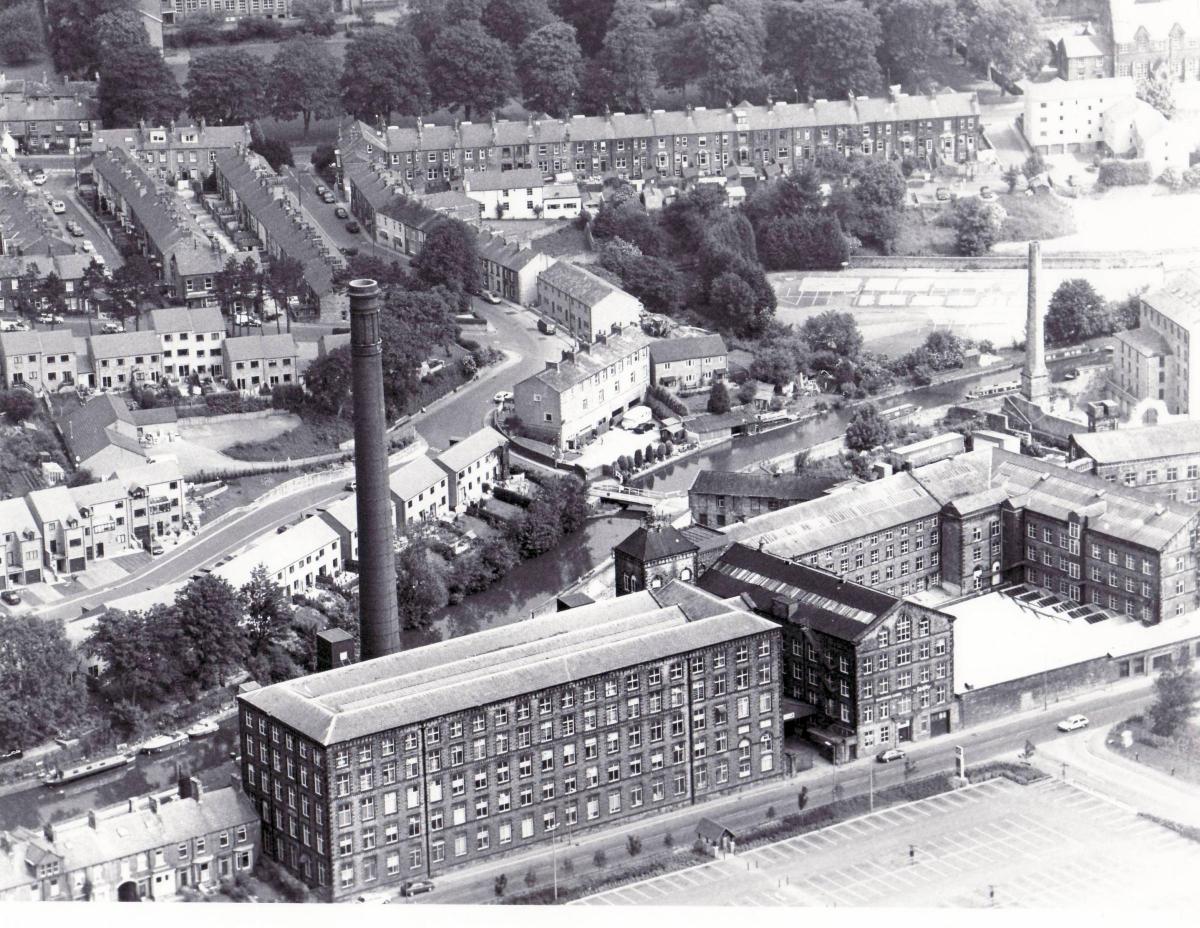

At Skipton, the major enterprise was Belle Vue Mills, better known as Dewhurst’s Mill, which was latterly owned by the English Sewing Cotton Company. The buildings were vast and blocky. A redbrick chimney with a height of 225ft had the visual emphasis of an exclamation mark. The dyehouse, straddling Eller Beck – “beck of the fairies” – gave the water some rainbow hues.

Each year, 7,000 tons of coal were delivered to the mill boilers, transported from the pits by barges that stirred the water of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. An old chap with a home-made barrow made of wood, with iron wheels, used a lacerated bucket at the end of a pole to recover coal that had dropped into the canal twixt barge and embankment.

Skipton, like many another West Riding town on which industry was grafted, had a grid-iron pattern of terraced housing: homes for the workers. Such houses had the uniformity of peas in a pod. Each had a cellar, where the weekly wash took place, the equipment consisting of a sink and a mangle with wooden rollers. These were treated with respect by those whose fingers had been crushed. The living room had an adjacent tiny scullery, complete with sink.

In her general appearance, my granny had affinities with the ageing Queen Victoria. When, usually on a Sunday, cards were being played for small sums of money, a table drawer was left partly open. If on the of-chance the rector would make a surprise visit, all the evidence for gambling might then be swept out of sight. The rector never appeared. And the gamesters, playing for coppers, afterwards redistributed them to ensure there were no losers in the 'slump' years when every penny mattered.

In the absence of a bathroom, a zinc bath, normally dangling from a hook in the backyard, was taken clatteringly in each Friday, which was Bath Night, being placed near the living room fire. Buckets of hot water were poured into the bath. A floating toy, usually in the form of a duck, would share the bath with a young bather.

The bedrooms had iron-framed beds. They were such chilly places that a brass warming pan with a long handle was available to hold hot embers. Swirled among the bedclothes, it took away the chilliness.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here