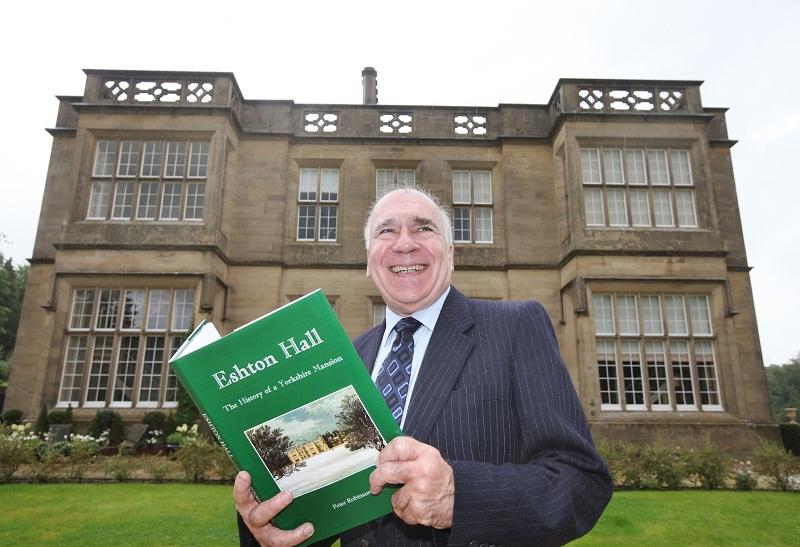

Peter Robinson recalls his school days with affection – so much so that he has researched the building where he was educated. He was a pupil at Eshton Hall School and has written “Eshton Hall: The History of a Yorkshire Mansion”. It details how the hall has evolved over the centuries and here we give a brief resume of some of its occupants

Eshton Hall has occupied its present site for more than 700 years – but its early history is quite obscure.

Records show that in the 12th century the manor was held by the De Eston family. They were well- connected, having married into the Romille family of Skipton Castle.

They held the lands for three generations until the last of the line, William, took part in the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. It seems he didn’t survive the campaign because shortly afterwards, the Eshton estate passed first to the Preston family and then to Henry Marton.

There was another change of ownership in 1551 when the manor was sold to Henry Clifford, the 12th Lord of Skipton and second Earl of Cumberland.

Henry was the bearer of the third sword of Queen Mary’s coronation in 1553 and was Lord Lieutenant of Westmorland.

He died in January 1570 and his estates passed to his young son, George. He became the most flamboyant member of the Clifford family and was a favourite of Queen Elizabeth, who loaned him ships for his naval expeditions.

In 1598, to help pay for a voyage to the West Indies, he mortgaged Eshton and the Nether Hesleden estate in Littondale, to Robert Bindloss for £2,000. A clause in the contract stated that if the sum was not repaid in five years, the purchase would be “absolute”. The money was never repaid.

The Bindloss family from Borwick Hall, near Carnforth, had amassed a great deal of wealth from the cloth trade. It is known that Robert and his wife, Alice, were living at Eshton Hall in October 1598 when their daughter, Alice, married Henry Banks, of Bank Newton.

The estate passed to his grandson, another Robert, in 1629. He was MP for Lancaster and High Sheriff of Lancashire. His wealth was legendary and there was a common saying in London, “as rich as Sir Robert in the north”.

Just under 20 years later, Sir Robert sold the Eshton and Littondale estates for £2,700 to fellow cloth merchant Mathew Wilson. At the time, Eshton Hall consisted of a central hall, great parlour, buttery, kitchen, brew house and garden house. There was a master chamber and seven other bedrooms.

Mathew continued his cloth business while, at the same time, developing life as a country gentleman, overseeing his 680-acre estate. But, eight years later, he died in London, leaving the estate to his nine-year-old godson, John Wilson.

The estate was held in trust until he was 21 and, on taking up residence at Eshton, John extended his inheritance by acquiring small parcels of land.

In 1700, John handed over the estate to his son, Mathew, and spent the remaining years of his life at Threshfield Hall.

Further generations of Wilsons succeeded to the estate and, as the wealth of the family increased, so did the size of the hall.

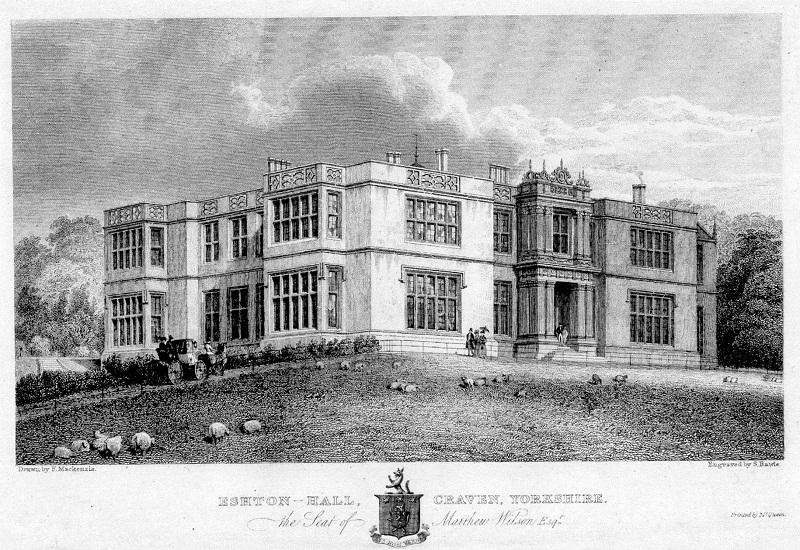

By the end of the 18th century, a large, but plain Georgian mansion had replaced the old hall.

A 15-year revamp started in 1825. A new wing was added, stables and estate buildings were erected, large bay windows were put in the drawing room and library, the columns at the entrance were redesigned and the grand staircase was repositioned to make a more impressive feature.

The hall’s distinctive clock tower was put up in April 1839 at a cost of £386s, but, to their consternation, the family had to wait 18 months before the clock itself was put in place. When the work was eventually completed, the then hall owner Mathew Wilson, his son and clockmaker Peter Clare climbed to the top of Sharp Haw to hear the bell strike.

Much of the work was financed by Frances Mary Richardson Currer, who was the daughter of Mathew’s wife, Margaret, by her previous marriage to Henry Richardson.

Frances’ stepbrother, another Mathew Wilson, became the family’s first baronet. He was Liberal MP for Clitheroe for two terms and was unseated after the 1852 General Election amid allegations that his agents had been guilty of bribery. He was returned to Parliament in 1874 as MP for the Northern Division of the West Riding of Yorkshire and, following a reorganisation, for the new Skipton division.

He died in 1891 and the estate passed first to his son and then to his grandson – the last of the family to live at the hall. His death in 1914 led to the hall being leased out.

The first tenant was Westlands School from Scarborough, which occupied the building for most of the First World War.

In 1923, the hall was leased to Arthur Stanley Wills, a director of WD and HO Wills Tobacco (Bristol) and later to another Scarborough school, Bramcote. It left in 1945, and just a year later, Ronald Purdy, a teacher at Bentham Grammar School, decided to set up Eshton Hall School.

It was to be a co-educational boarding school, with a limit of 100 pupils, and his aim was to preserve the individuality of pupils and to develop any talent they might possess. He and his wife, Mary, remained there for eight years before the school was taken over by former actor Christopher Rowan-Robinson and his wife, Audrey.

In 1958, Mr Rowan-Robinson approached the Wilson family solicitor to see if they would consider selling the hall and part of the estate. A price of £18,000 was agreed and the sale was completed on December 3, 1959. The school subsequently became an educational trust and received a £10,000 grant from local benefactor Jessie Coulthurst.

The Rowan-Robinsons retired in 1964, to be replaced by Mr and Mrs Baldwin, from the Cathedral School at Hereford. Alas, just a year later, it was announced the school was to close at the end of the summer term in 1966.

The hall was bought by Mrs Coulthurst, who subsequently sold it for £11,500 to Mr and Mrs Unwin, of Sutton-in-Craven. They converted it into a nursing home, with 36 single rooms and two shared rooms, and ran the business for 20 years.

In 1987, it was bought by Jim and Sue Brosnan who continued to run it as a nursing home until mounting costs forced its closure in 2002.

The latest chapter in the hall’s history began in May 2003 when it was acquired by Penrith-based property developer Dare (Northern) Ltd.

It won planning permission to convert the historic hall into 13 apartments and five cottages before selling the site to Burley Property Developments of Ilkley. Working with English Heritage and the Yorkshire Dales National Authority, the company completed the first homes in April 2005.

It is now a very sought-after place to live.

Eshton Hall: The History of a Yorkshire Mansion is priced at £20 and is available from the author on 01282 866406 or email aprobinson@waitrose.com.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here