Three members of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club will recreate a climb undertaken by Craven mountaineer Cecil Slingsby 125 years ago. Here club member Michael Smith looks back on the expedition which made Norwegian mountaineering history.

AT the head of Norway’s longest fjord, under the Jotunheimen peaks, the local community will gather today to celebrate a Craven mountaineer’s solo climb in Victorian times.

And three members of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club hope to be back down from the mountains in time to join them to remember one of the club’s founder members.

This all started in the summer of 1876 when Cecil Slingsby, of the Carleton Mills, made his fourth visit to Norway. In Oslo, Cecil met up with the experienced mountain guide and reindeer hunter Knut Lykken and schoolmaster Emmanuel Mohn.

Together they planned and successfully completed an expedition unique in Norwegian mountaineering history with five first ascents in just five days.

Then came the ‘big one’ Store Skagastølstind, or Storen for short, a rock tower reaching to almost 8,000 feet. After a day’s rest at a cabin high up the valley, the three set off about 7am, since with round-the-clock daylight there was no need for an especially early start.

Rounding a spur and tramping up a broad valley, they had difficulty in poor weather finding a way over the rough ground. They crossed a ridge and scrambled down into another valley before climbing up a steep glacier and the rocks above. Though Slingsby’s nailed boots were fine, on the steeper parts the Norwegians’ boots hadn’t enough grip and Mohn tottered a couple of times but was fortunately held by the rope.

By early evening they were below the fearsome final rock tower of Storen with Mohn and Lykken both tired and certain that the climb was impossible.

Still fired up with enthusiasm, Cecil went on alone for the last 500 feet – unroped of course – struggling to get over an overhanging ledge at one point. He made it to the top, built a cairn and secured his large handkerchief to it. That overhang proved difficult to reverse on the descent and Cecil needed to use his ice-axe to lower himself, but he got down and caught up with the others on the glacier.

It took until the early hours of the next day before they regained the cabin to sleep.

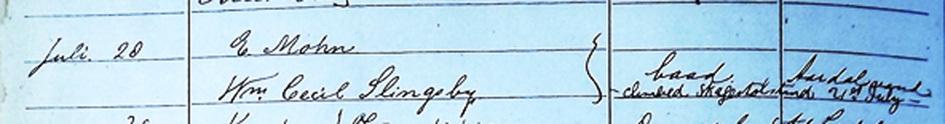

They descended eventually to Årdal and news of the climb spread quickly. On their way over a pass through a telescope they could just make out the handkerchief fluttering on the summit. Slingsby made a note of the ascent in the fjord-side Klingenberg Hotel’s visitors’ book as he and Mohn relaxed. Besides celebration of the achievement there was inevitably criticism of the Norwegians’ failure to make the ascent of such an iconic peak and letting the first ascent fall to an Englishman. Mohn was troubled by this criticism and it may have contributed to him taking his own life by drowning almost 15 years later.

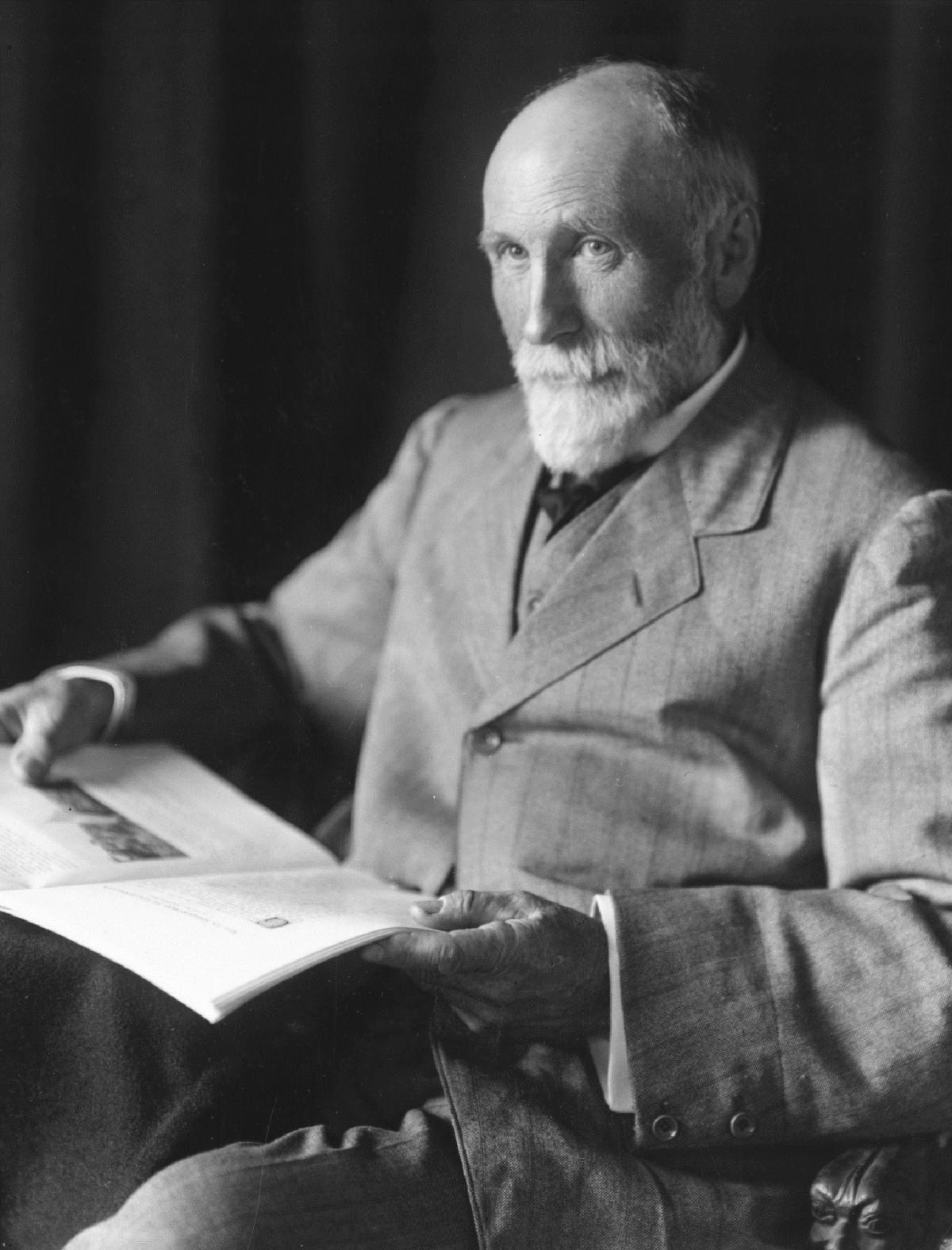

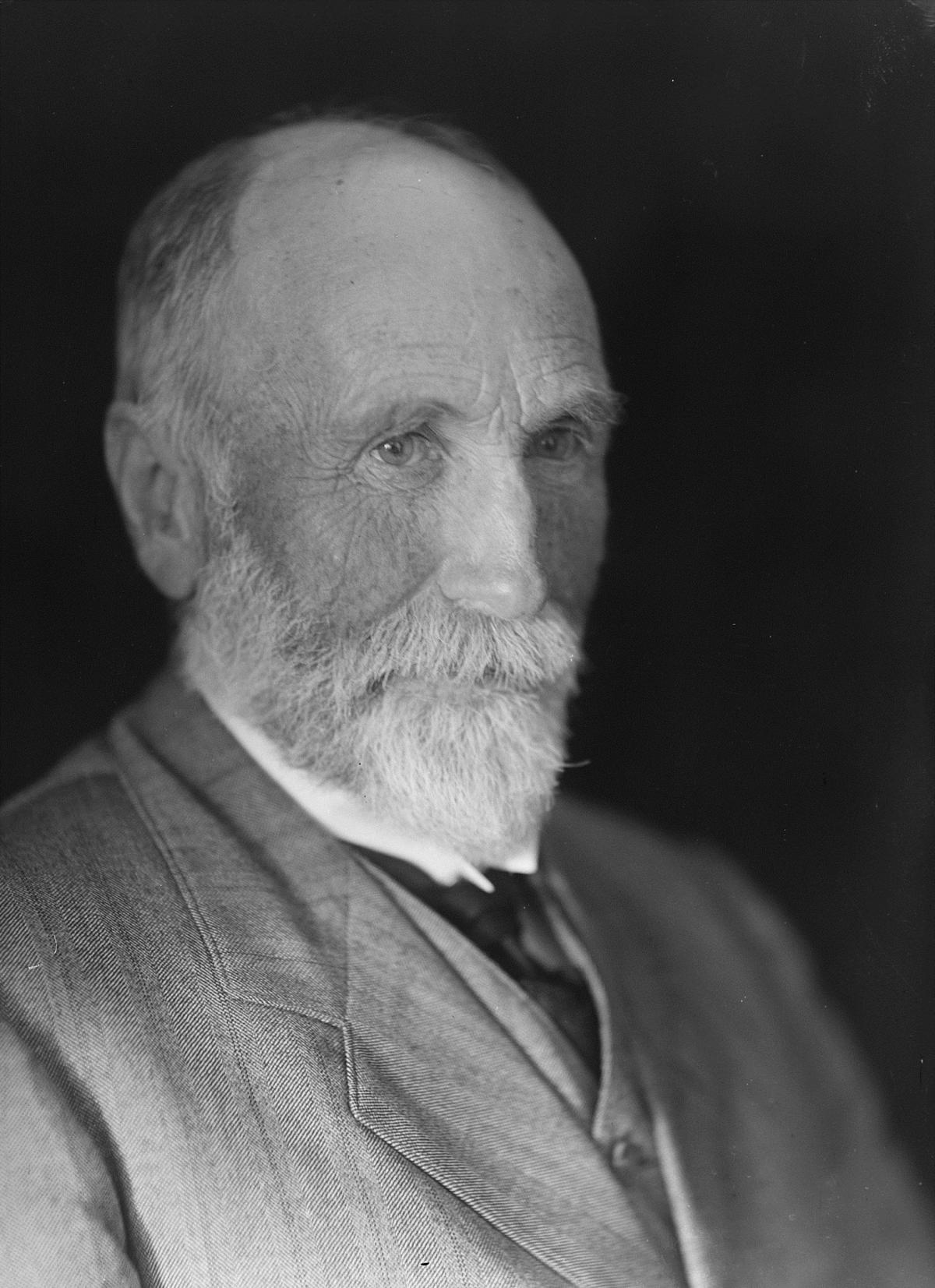

Slingsby’s ascent, together with his many others throughout Norway over 20 visits, led to him being called the Father of Norwegian Mountaineering. He is still well-known as such to this day in Norway but rarely remembered in Britain. Later, an ageing Cecil had an audience with King Haakon VII and the papers reported his visit almost as if it was a royal tour.

The Årdal community are celebrating the 140th anniversary of the Storen climb and members of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club will be joining them. Earlier this week, Ilkley’s Peter Chadwick and Sheffielder Michael Smith met up with Norwegian member, Kjetil Tveranger at the modern Klingenberg Hotel. Together with the hotel’s mountain guide, Torunn Laberg, they are trying repeat the ascent taking a day to reach a high mountain cabin.

They may need to use a route to the left of Slingsby’s as a shrinking glacier and increased stonefall have increased the difficulties there. Last night, they planned to stay in a small shelter on a col before attempting the climb today. There is no guarantee of success as good weather will be needed and all involved are more than double Slingsby’s 27 years on his great day.

After the holiday, Cecil returned to his family and his work and went back to playing the organ and singing with the choir in Carleton church.

Despite his long absences from the mill on holiday and as the buyer and salesman, he would have been warmly welcomed back and there would surely have been pride his achievements. Cecil kept a careful record of his mountaineering and, in 1904, published a seminal account in “Norway: The Northern Playground.” That book is still in print!

Slingsby encouraged mountaineers and tourists to visit Norway through lectures and by inspiring those he met. He gave a lecture to the then infant Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club on the Norwegian mountains and became the club’s second president. His climbing was not restricted to the one country.

He made first ascents in the Alps and brought his two exhausted companions off a French peak on their third day out. Locally, he frequented many Yorkshire crags and has a pinnacle and chimney route on Crookrise crag above Skipton, another on Scafell in the Lake District and a winter climb on Ben Nevis, all named after him.

Reaching its 125th year, Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club is still going strong and continues to welcome new members. The ‘ramblers’ has always been a bit of Victorian whimsy, as members have caved, climbed, skied and explored worldwide from the outset, besides enjoying regular weekends away in British mountains.

This year they have three get-togethers at their Clapham cottage-cum-bunkhouse besides trips scrambling in Morocco, trekking in Nepal, winter climbing in Scotland and walking on the islands of St Kilda and Harris.

The club has built on Slingsby’s connections with Norway by working with the Slingsby Trust, a charity supporting Årdal youngsters getting out into the mountains. In 1992, the club’s centenary year, three dozen members worked with local mountaineers to climb all of Cecil’s Norwegian mountains.

We will have to see if these three members can make their 140th anniversary ascent of Storen.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here