Jane Houlton’s book, An Almshouse for Linton, has piqued the interest of Craven Herald readers with its account of the origins of Linton’s iconic Fountaine Almshouse. Here Stephen Stead reveals further intriguing facts from the Fountaine family’s closet.

RICHARD Fountaine , who lived from 1639 to 1722, was the remarkable Yorkshireman who, despite being born into modest circumstances in Linton, near Grassington, became a highly successful merchant haberdasher in the City of London. When he died he left the equivalent of £8 million in today’s money, and part of that money was used to endow the splendid Hospital Almshouse in Linton that still bears his name.

He also left substantial sums to his Linton nephews, nieces and other relatives – some receiving as much as £1,000 (£200,000 in today’s money).

The Fountaine and Hewitt families were independent farming folk, but not rich or of gentle birth. Sudden wealth of this kind must have greatly elevated their financial and social position, so much so that a number of the family began to use the Fountaine coat of arms that Richard Fountaine himself had adopted. These are the very arms which are engraved on the grave slab of Richard and his wife Elizabeth in the chancel of his parish church in Enfield, Middlesex. They are a set of marital arms – joining Richard’s with the arms of the Jekyll family, to which Elizabeth had belonged. Yet, as will be seen, the Fountaines’ use of these arms was not without controversy.

In 1865, John Varley, a Skipton architect with a keen interest in conserving buildings and memorials of local history, wrote two letters to the Craven Weekly Pioneer, published in April of that year. In these, he records various memorials relating to the Hewitt and Fountaine families of Linton. He notes that there was, in St Wilfrid’s church, Burnsall, a Fountaine family escutcheon (a shield bearing a coat of arms) fixed on the wall above the former site of the grave of Christopher Fountaine, Richard’s great-nephew. He describes it as:“an escutcheon, on which is emblazoned the family coat of arms, consisting of three sable elephants’ heads on a gold shield, with red fess bend; above the shield is an Esquire’s helmet in profile; over which, on a wreath, is the crest – a golden elephant’s head; at the foot of the shield, on a ribbon, is the motto “EN CAELO QUIES”.

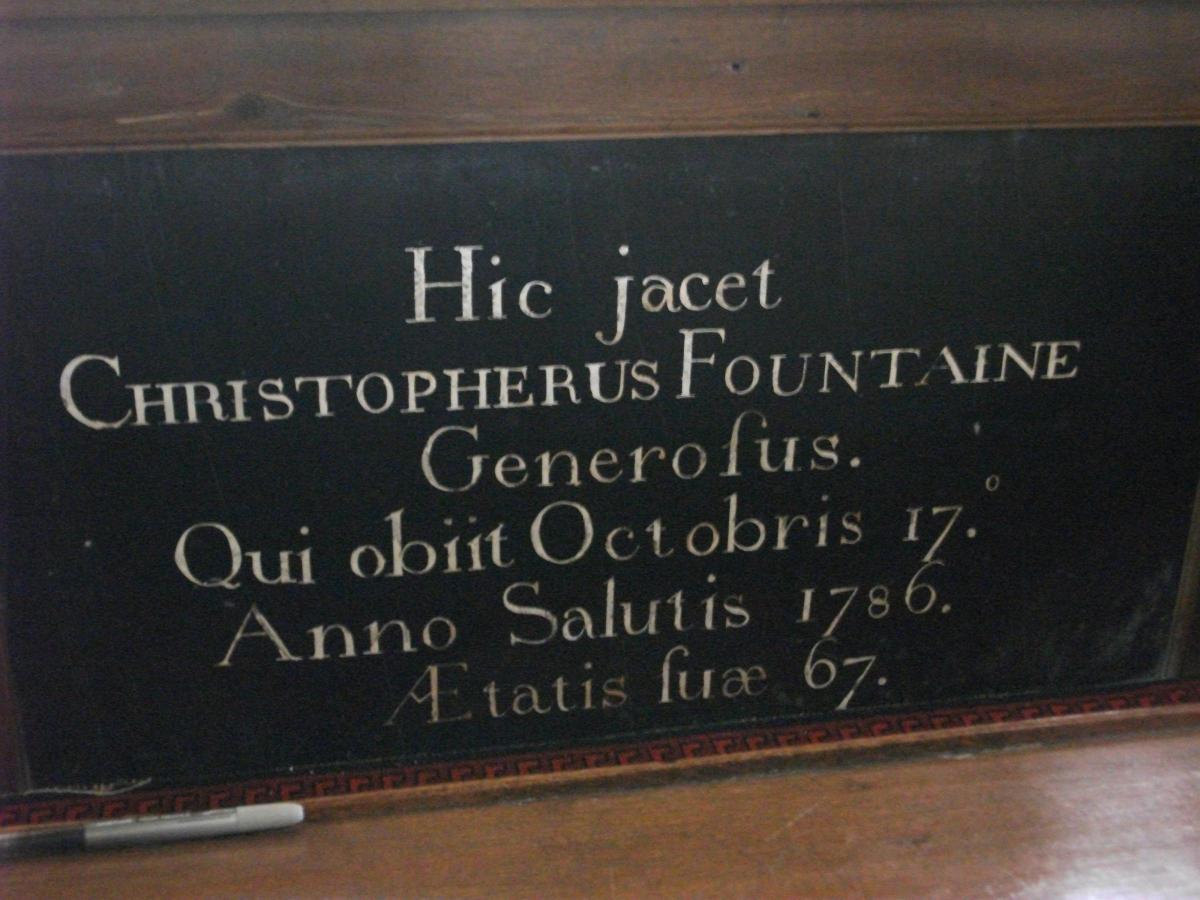

As Varley states, Fountaine’s descendants and heirs were using a version of his coat of arms in the late 18th century, 50 to 60 years after Richard Fountaine’s death. Unfortunately these memorials no longer exist, although a plaque commemorating Christopher Fountaine’s grave is still placed on the backrest of one of the chancel pews in Burnsall church.

Yet it transpires that Richard Fountaine and his descendants were never entitled to bear arms at all. The College of Arms appraised the grave slab arms, and that was their conclusion. Moreover, the coat of arms that he was using has some elements which were considered incorrect and highly irregular.

For example, the dexter (right) side of the shield bears a crest and arms with elephants’ heads, which were arms granted to the Founteynes of Salle in Norfolk, a family to whom Richard Fountaine’s family were not known to be related at all. (The College of Arms suggest that the use of the elephant’s head might have been a pun on the surname Fountaine, as the spraying of water through the trunk of an elephant might resemble a fountain).

Also, the sinister (left) side of the shield bears the arms of the Jekyll family, for Richard’s wife was Elizabeth Jekyll. The crest of the horse’s head above the shield was also granted to the Jekyll family, but this is once again an improper usage because a man has no right to adopt the crest of his wife’s family. The helm with a closed visor below the crest, above the shield, conventionally denotes an esquire or a gentleman – yet Richard was of humble stock in Linton.

The College of Arms describe this, with some degree of tact, as an “odd marshalling of arms”. It is obviously intended to be marital arms, showing the union of the Fountaine and Jekyll families by marriage. We can only surmise that Richard Fountaine has chosen to display or use the arms of the unrelated Founteynes of Norfolk, without entitlement, to give a more favourable impression of his own origins.

Of course, the practice of the irregular use of arms had long been widespread, and between 1530 and 1687 there were Heralds’ Visitations authorised by Royal Commission by county or district to ensure that arms were borne with proper authority. Anyone using arms without entitlement could be publicly humiliated by being forced to disclaim any pretension to arms or gentility, and cases of abuse could be brought before the Court of Chivalry. After 1687 matters changed and it was left to an offended party to take legal action over the misuse of arms, rather than for the Heralds to act.

Indeed in 1687 there was a Visitation of London by the Heralds, and in advance of the main visitation, the Beadle in each City ward was obliged to make a list of the inhabitants of rank and substance who might be using arms. A Richard Fountaine, “Haberdasher of small wares”, was listed in St Lawrence Lane in the precinct of Cheap ward, and was summoned to appear before the Heralds on September 26 1687 at the Irish Chambers in Guildhall. Yet curiously, Richard Fountaine was found to be “in the Countrey”, a fact confirmed by a list compiled by the Constable of the precinct. Thus Fountaine avoided social disgrace and public humiliation by never appearing before the Heralds to have to explain his “odd marshalling of arms” and his “borrowing” of someone else’s arms. By sheer coincidence, he was mysteriously out of town.

Fountaine obviously continued to use the arms, however, since they are on his grave slab, and were used by his descendants. In the inventory of his house in Enfield three Coats of Arms are on display in the Hall of the house, presumably including the irregular marital arms to be found on his grave. His descendants clearly had no reservations about using the arms – displaying them in church and on gravestones, reflecting their enhanced, moneyed status. We can only guess at how this was received amongst their neighbours here in the Dales!

For Richard Fountaine, who had married into the powerful and eminent Jekyll family, this was no doubt a sign of a need to keep up appearances, and to mix as an equal in the circles of wealth and power in which he lived and traded. This need no doubt prompted him to endow Linton’s famous almshouse. And for Fountaine’s newly wealthy Linton descendants the use of the arms was perhaps more a mark of ambition and vanity, elevating them above their Wharfedale fellows.

The controversy surrounding the coat of arms can be added to a list of scandals which includes the row over Christian Fountaine’s clandestine marriage and the furore over the will that ended up in the Court of Chancery – all discussed in detail in Jane Houlton’s book.

An Almshouse for Linton by Jane Houlton (Devenish Press 2018) is available from Skipton Tourist Information Centre, Yorkshire Dales National Park Centres, Grassington bookshops including the Dales Book Centre, or online from: bit./lyRichardFountaine.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here