THE sinking of the Lusitania nearly 100 years ago claimed the life of a Craven woman. Lesley Tate investigates.

ROBERT and Clara Hebden were on their way home on a surprise visit to family in Barnoldswick in May, 1915, when disaster struck.

It was the young couple's misfortune to be on the British Cunard liner the RMS Lusitania, which was struck by a torpedo fired from a German U-boat and sunk off the coast of Ireland.

The sinking, carried out early in the First World War, helped turn public opinion against Germany and contributed to America joining the war in 1917.

A warning had been issued by the Imperial German Embassy that a state of war existed between Germany and Britain and her allies and that any vessel travelling within the war zone was liable to be destroyed.

Published in 50 newspapers across America, including in New York, from where the Lusitania set off on May 1, the warning - placed next to an advertisement of the ship's return journey - said any passengers choosing to board such vessels did so 'at their own risk'.

In addition, the Lusitania had been carrying shells and cartridges - a fact denied at the time.

Twenty-eight-year-old mill worker Clara Hebden was one of the 1,142 on board the Lusitania to lose their lives. Her husband, who had been on another part of the ship when it was attacked, was one of the 761 survivors. He continued his journey home to Barnoldswick, where he buried his young wife at the town's Gill Church.

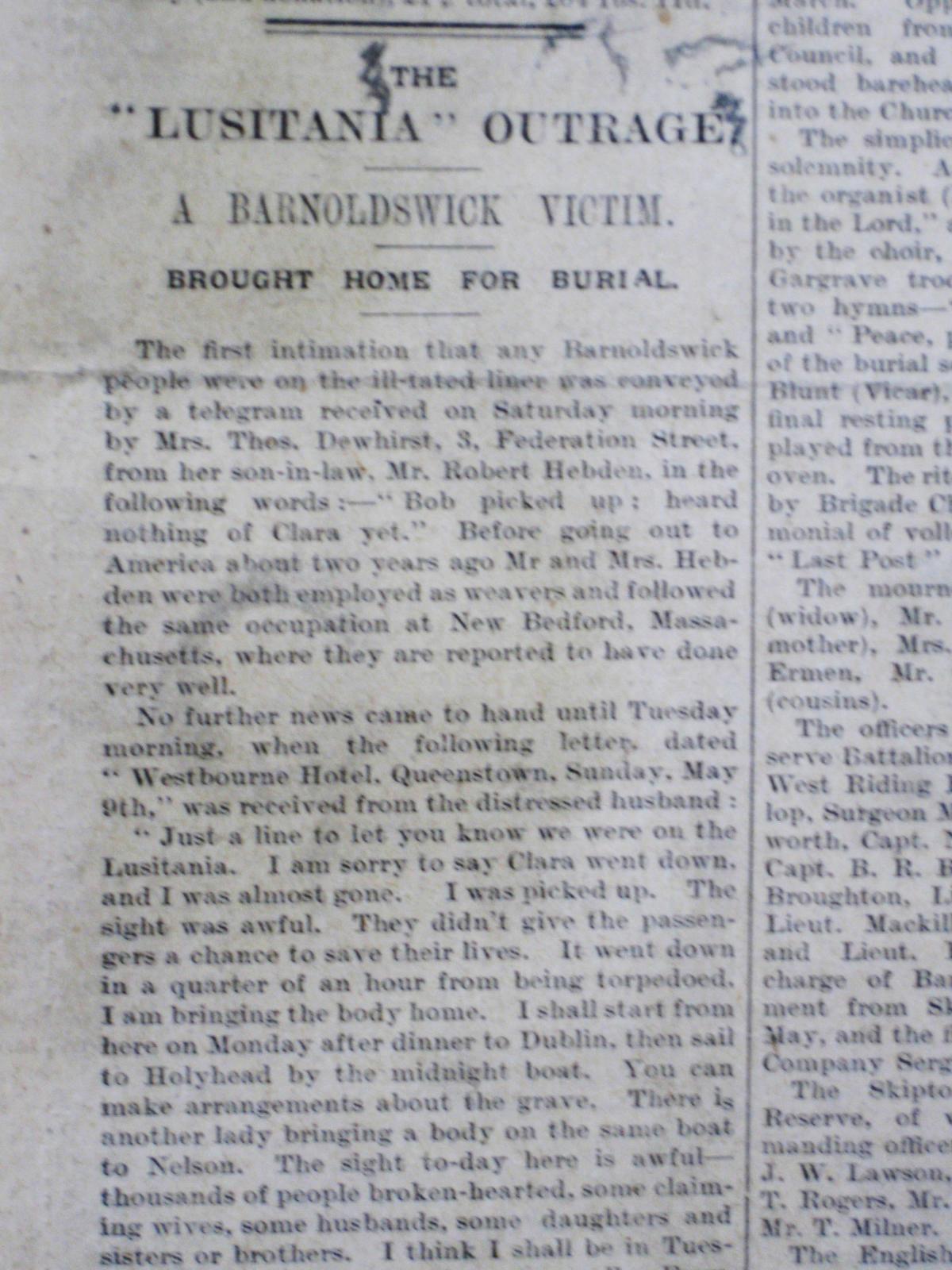

The first anyone had known the couple had even been on the ship was when Mrs Hebden's mother in Federation Street, Barnoldswick, received a telegram informing her 'Bob' had been picked up, but that Clara was missing.

The couple, both weavers, had left Barnoldswick two years before for new lives in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Nothing more had been heard of them at home until May 1915 and the fateful telegram.

It was quickly followed by a letter from Mr Hebden written from where he had been taken, in Queenstown, Ireland.

In his letter, Mr Hebden said Clara had gone down, and so almost had he.

"The sight was awful," he wrote. "They didn't give the passengers a chance to save their lives. It went down in a quarter of an hour from being torpedoed."

Mr Hebden continued that he was bringing his wife's body home for burial and would be travelling to Holyhead from Dublin by boat.

"The sight here is awful," he continued. "Thousands of people are heartbroken, some claiming wives, some husbands, some daughters and sisters or brothers."

Mrs Hebden's body was met at Barnoldswick Station by a hearse and conveyed to her mother's home.

Mr Hebden said how he and his wife had intended their visit as a surprise and had planned to send a telegram from Liverpool.

Up until the time of the disaster, the couple had been enjoying a splendid voyage.

Mr Hebden had been walking round the ship's lower deck when the explosion had taken place.

His wife had not been with him at the time and he had never seen her alive again.

"I made my way to the second-class deck to one of the boats, but while it was being lowered, it tilted, precipitating nearly all the occupants into the sea.

"Getting into another boat, the plug came out of the bottom, and it filled with water, so that we were scrambling for our lives in clinging to the boat, which kept reversing," he wrote.

"Eventually, we managed to climb onto the upturned boat and remained in that position for one and a half hours, thinking every moment would be our last.

"Subsequently, we got onto a collapsible boat. During all this I never saw anything of my wife and was not aware that her body had been recovered until I identified it in the mortuary," he finished, signing himself off as "your heartbroken son-in-law".

Mr Hebden added he had seen nothing of the U-boat and had heard nothing of the warning in the New York papers issued by the German Embassy until after his arrival in Queenstown.

Mrs Hebden's funeral took place at Gill Church. A large crowd assembled in Federation Street before the cortege left the house. Amongst the mourners were two other survivors, Mrs Duckworth of Blackburn, and Arthur Scott, of Nelson. Her coffin was covered with floral tributes, including from her former work colleagues at Westfield Shed, and also from Barnoldswick Conservative Club.

Sadly, two years later, Mr Hebden also became a victim of the war.

While serving with the Northumberland Fusiliers, he was killed in action on April 2, 1917. He was just 36.

The father of Mary Ann Moore, of Cowling, had also been a passenger on the Lusitania.

Edwin Moore, a foreman pattern maker in Rhode Island, was returning home on one of his regular visits to see his daughter.

She had been on her way to Liverpool to see if he had survived and had been turned back at Colne, her father's name not being on the list of survivors.

A couple of days later, she had set off for Liverpool, intending to continue to Queenstown, but was told the bodies would be buried before she arrived.

The Cunard Company gave her no hope of her father's survival, all she could do was wait at Liverpool for photographs of unclaimed corpses.

Mr Moore had gone to America 40 years earlier. He made frequent visits home and always stayed with his daughter in Lane Ends, Cowling.

The sinking of the Lusitania horrified the civilised world, reported the Craven Herald.

"The dastardly act was received with righteous indignation by all nations where civilisation reigns; in Germany it was greeted with exultation," wrote its leader writer.

Describing the sinking, the Herald reported there had been 'no panic' as few seemed to think the ship would sink "The vessel was struck by two torpedoes, but neither the captain nor his officers saw the submarine which fired them. The torpedoes entered the forward stokehold, and the engines were paralysed by the breathtaking of the main steam pipe.

"The vessel was steaming at 18 knots, and, as it was impossible to reverse her engines, she made way for about ten minutes. The boats, accordingly, could not be lowered immediately, and the starboard boats were useless, owing to a heavy list.

" About ten or a dozen rafts got away. The Lusitania sank about ten or 20 minutes after she was struck, and the majority of passengers and crew went down with her.

"Some, like the captain, floated clear, and were picked up by the rescue ships which reached the scene of the disaster two or three hours later."

The Herald continued: "Among the bodies found were that of an heroic sailor with a little child strapped to his shoulders, two children who were drowned were found locked in each other's arms."

At the inquest, Captain Turner placed it beyond doubt that no warning had been given to the Lusitania before she was fired at. He also stated that, as far as he knew, no application had been made to the Admiralty for protection.

The finding of the inquest jury was: "We charge the officers of the said submarine, and the emperor and government of Germany, under whose orders they acted, with the crime of wilful and wholesale murder before the tribunal of the civilised world."

The Herald reported there had never been a "greater infamy in the world than the deliberate and premeditated sinking of the Lusitania without a moment's warning".

It made a plea to all those men who had yet answered the call to join up. "How any self-respecting young man, who is eligible and at liberty to serve his king and country, can now stand and 'wait to be fetched' passes a Britisher's comprehension."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here