IN the springtime of the year 1990, when I was taking an evening history course at Settle, under the auspices of Craven College, No 18 in the series was entitled The Romantics.

It related to the period 1760-1820 when the caves, crags and chasms of High Craven were being visited by people who had taste and leisure.

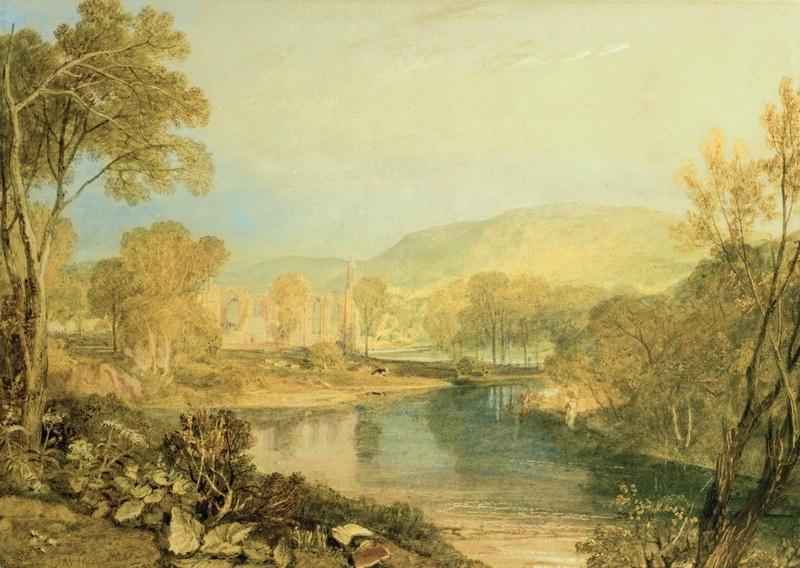

When looking for sublimity, the Romantics found it in popular caves and, also in such a gloriously visible limestone feature as Gordale Scar (at the head of Malhamdale). Using a “Claude Glass” they studied a reflection of the landscape – on which they turned their backs! This also applied to unnatural but magnificent features such as Bolton Priory, in Wharfedale.

Visiting features in this so-called Romantic period might have been a revolt against the sterility of classic conventions. Dominating art, literature, music and architecture they provided a quest for novelty at home. War with France had discouraged visits to the Continent.

A few intrepid tourists were impressed by natural spectacles in Craven, the Lake District, Wales and Western Scotland. Their writings attracted others. From the 1770s onwards, a tour of the mountains, lakes and dales of Cumberland and Westmorland was incomplete. Visits were paid to features on the vast stretch of limestone country in Craven.

Thomas Gray (1769), visiting Gordale Scar at the head of Malhamdale, was greatly impressed by the waterfall. He wrote about what he referred to as The Scar which “overshadows half the area below with its dreadful canopy where I stand.” John Hutton (1781) was fascinated by caves in the Ingleton district.

At Bolton Abbey, in Wharfedale, some early English landscape painters – Girton, Cotman and Turner – set down set down their impressions in a freer, more colourful way than had been the custom in painting. There was a demand for ruins, preferable those decked with ivy and having a tinge of romance.

John Hutton, a Kendal clergyman, responded with some emotion to the Caves of Craven. His mind was also capable of assessing scientific fact. In his book, Tour of the Caves. published in 1781, he rightly deduced from fossil evidence in high places that the limestone had a marine origin. Then, being a cleric, he reconciled this with the Biblical story of The Flood!

Guides at the caves included William Wilson, an old soldier who lit up the calcite formations with lanthorn and candlestick. Houseman (1800) went with Wilson to Yordas Cave, where the guide “now places himself upon a fragment of the rock and strikes up his lights consisting of six or eight candles, put into as many holes of a stick.” Each, fixed at the tip of a long pole, meant that he could “illuminate a considerable space.”

By 1830, the Romantic Age was waning and in 1837, with the discovery of the further reaches of Clapham Cave, at the head of well-watered Clapdale. The scientific aspect was being stressed. The first-known potholers were John Birkbeck and William Metcalfe. These men had taken a close look at some of the gaping shafts on the fells.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here