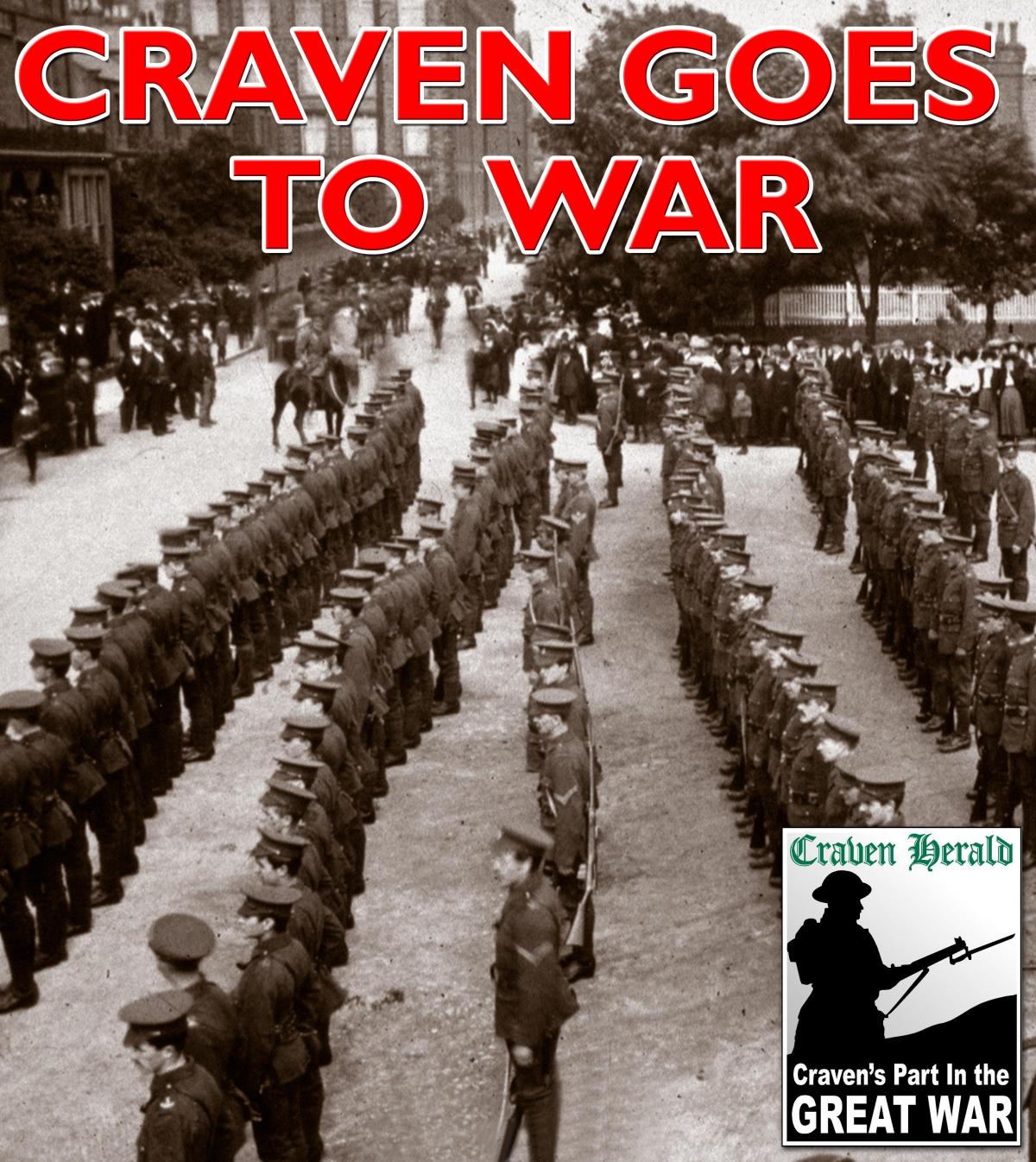

WITH the introduction of conscription in the spring of 1916, the option not to join up in the First World War - the armed forces had relied mainly on volunteers up to then - had been removed. The only way men could escape a military uniform was to appeal to a tribunal. Clive White looks at the background of the men who were appealing for exemption.

BY mid 1916, the reputation of the military tribunals which met weekly to rule on who should or should not be recruited to the armed services was at a low ebb.

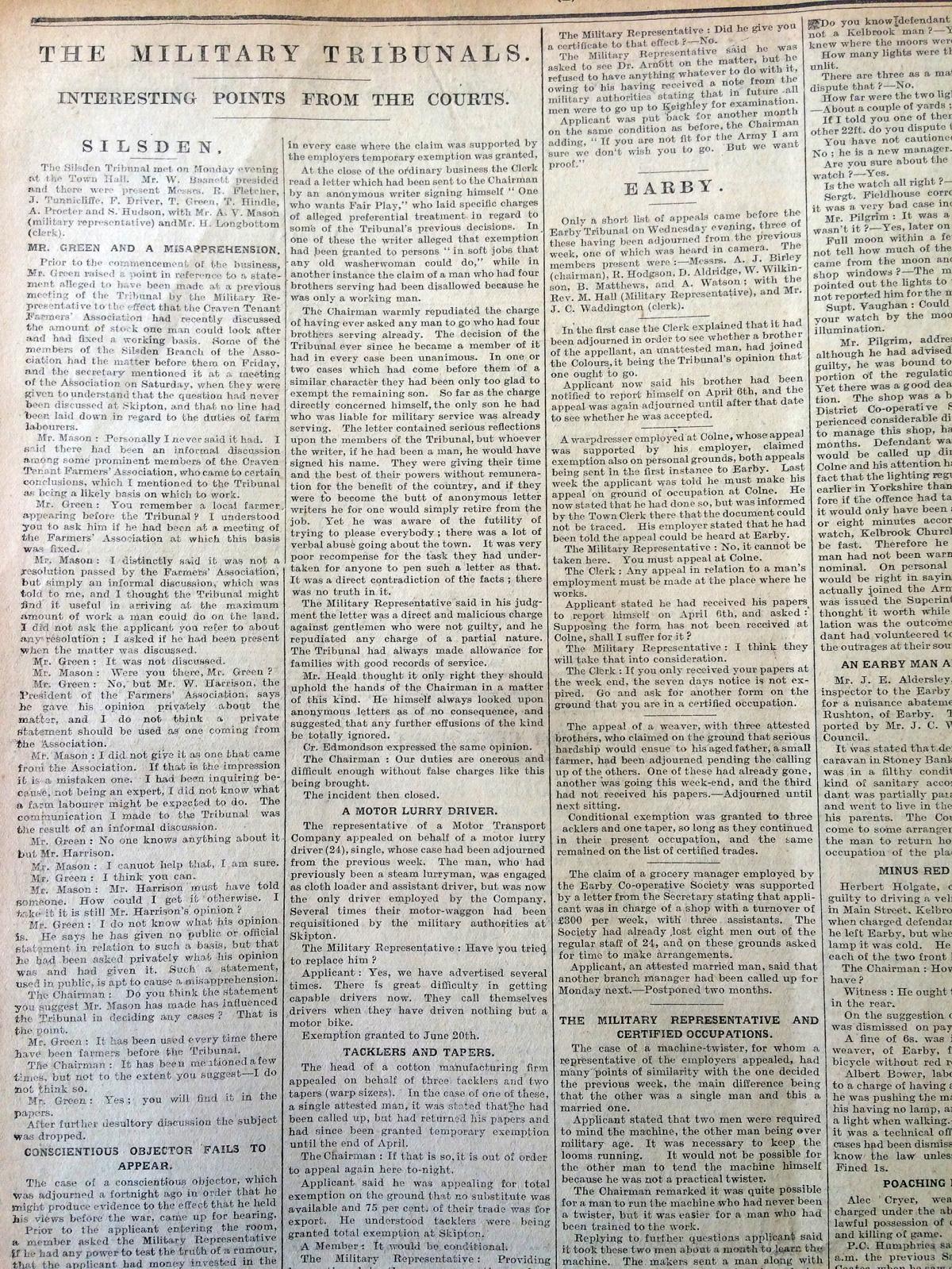

The all-male hearing which included a military representative was a target for verbal abuse and after one outburst, the chairman hit back claiming: "Our duties are onerous enough without false charges like this being brought."

He was responding to a disgruntled warp dresser from Skipton who had been refused exemption despite backing from his employers and his claim of personal hardship.

He had told the bench that there were others working in the same room as himself who were younger and had been granted exemption for three months. Few men at the time were given full exemption from combat and if they did convince the tribunal to spare them the conflict, it was usually only for a few months.

As our Skipton warp dresser exited the room he barked: "Do you call yourself men?" Not much of an insult these days.

Earlier in the hearing they had dealt with a man who failed to turn up, but in a letter complained about their earlier refusal to exempt him from service.

He accused the panel of "exempting people in soft jobs that any old washerwomen could do." The tribunal chairman responded with: "If this letter writer had been a man, he would have signed his complaint."

Even a dental mechanic aged 22 and single wasn't spared his marching orders despite support from a representative of the military who said the job was vital to the dental hygiene of the newly recruited men who occupied the camp in Skipton. His call-up papers were put back two months.

A wages clerk from Skipton also got short shrift at his appeal despite support from his employer who, when asked if he had tried hiring a woman, of all people, admitted he had not. He was then told his clerk would be called up and that he should try harder to find a replacement.

But a man from Cowling was granted exemption in July 1916 when the bench said he could stay in civvy street until September. He told members of the tribunal he was a grave digger and also dealt in poultry so he was in demand. Despite a comment by the tribunal that Cowling was a health place and "people rarely die there", he won his appeal.

And another man, a master clogger and boot repairer living in a village near Skipton - we're not told which - was granted exemption from military service ironically because he could not march and was the only cobbler in the village.

Among the hundreds of appeals, there were a number from conscientious objectors who had already been given exemption from combat. Many conscientious objectors accepted non-combatant roles in the army, such as stretcher bearers.

But there were a fair share of these men who on principal objected to any role which had links to military service, even in some cases objecting to carrying out work in industries producing military equipment. A good number seemed to lose their appeals and were told they must carry out their non-combatant roles. What happened to these men if they still refused is not revealed in the Craven Herald.

Men like Robert Leach, 21, from Addingham, a member of the local church, who told the panel he objected to military service of any description, including making munitions or other war materials, had his appeal dismissed, the Craven Herald headlining the story "A Shirker from Addingham".

A 27-year-old from Airton told the tribunal he couldn't fight because he was waiting for the time when the world would become a "brotherhood of man". He got his marching orders.

Robert Elsworth, a baker of Barnoldswick, who also objected to serving in a non-combatant role, said he had protested and engaged in propaganda against the war for several years. He was a member of the Independent Labour Party and based his principles on the Old Testament.

He told the tribunal that even accepting a role as a non-combatant would go against his principles. "I should be assisting others to do what I would not do myself. It would be equivalent to preaching a temperance sermon on Sunday and asking for a job as a brewer's drayman on Monday," he cleverly argued. It made no difference, his appeal was dismissed.

Christian principles were high on the list of reasons but few of them moved the hearts of the tribunal panel.

Like John Thomas Barker of Ings Avenue, Barnoldswick, who claimed sending him to war would be to force him to serve two masters.

He said: "Having sworn allegiance to the principles of Christ, I could not conscientiously take any part in war. Having sworn allegiance to the King of Kings I could not swear allegiance to an earthy King."

He failed to impress the tribunal and was ordered to take up non-combatant service.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here