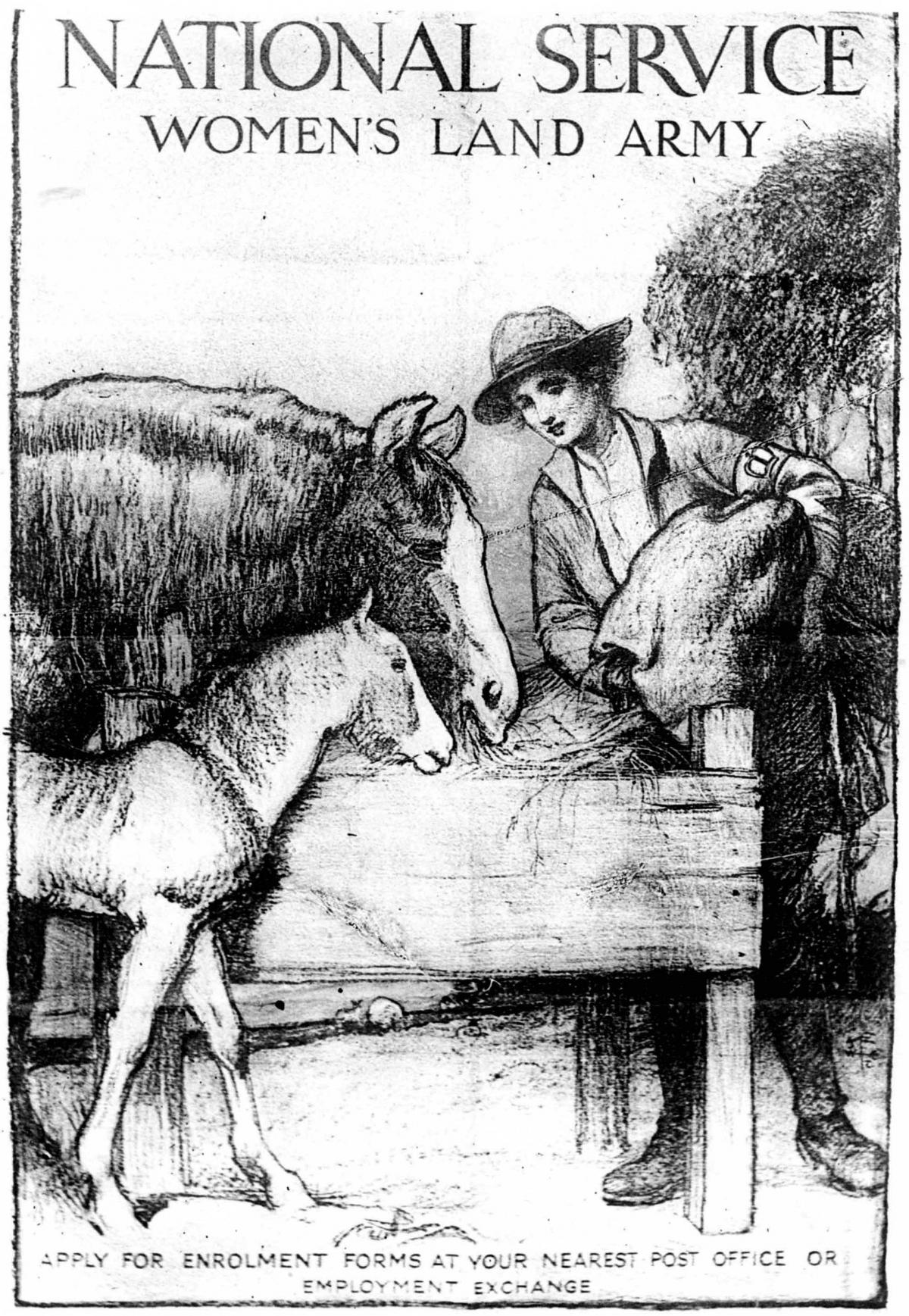

"HAVE you tried to get women to work on the land?" Was the question much heard at the military tribunals of 100 years ago. Weekly courts were held in Craven and across the country to hear applications from men, often with evidence from their mothers and employers, why they should be exempt from being called up to fight. Some were allowed temporary reprieve of a month or two, while very, very few, even conscientious objectors, were allowed permanent exemption.

In Craven, the plea of the farmer was often heard at the tribunals. Farmers were generally allowed exemption and went to the tribunals to appeal for their workers to be exempt too. And, asked by the tribunal chairmen whether they had considered women, the answer generally came back that women were unable to carry out the heavy work of ploughing, harrowing and manuring. In some cases the farmers also objected to the women carrying out milking, which not so long earlier had been peculiarly women's work.

The Craven Herald reported however, that change was coming over the 'gentler sex' - their patriotism and public spirit inspiring them to undertake duties which no-one in more peaceful times would have dreamt of them taking on.

A farm in Lincolnshire had been at the forefront of showing what women were capable of. Women worked for hours in ploughing, in threshing operations and in spreading manure. And in all the tasks, the women were said to have performed well and with competence. The Craven Herald urged farmers to think again and asked the most sceptical to give women a trial at the very least.

At a Skipton tribunal hearing, an employer already employing many women, applied for exemption for a warehouseman and a clerk. He said the firm had lost nearly all men of military age and it was essential that at least one or more of the staff remained with experience. The young clerk also carried out the hoist work, which was too heavy for females. All of the ordinary clerk work was being carried out by women, he said, adding he already employed 19 women and girls. However, it took two women to do the job of one man - a claim that caused much laughter from those on the bench.

At the same time, the Herald's weekly Ladies Column, raised the subject of women's employment in war time. Reports from various employment bureaux and agencies had shown a rapidly increasing demand for women - and not just in agriculture.

Demand was for women in the commercial and industrial worlds, but only for women under 40 years old. There was little demand for the more mature woman - even though men were still being conscripted into the forces between the ages of 18 and 41 by April 1916, and also married men. There was even less chance for the older woman who had never worked in her life - a housewife, bringing up children, counted for nothing.

Nurses were in particular demand as were cooks, who were also the best paid, as long as the woman was qualified and capable. It was expected that more women cooks would be employed at soldiers' camps and in hospital kitchens, where previously the men in charge were often ignorant of cooking and of nutritional requirements.

The results were appalling, commented the Herald; the sick and wounded suffered even more from being given the wrong food, and waste was huge. Those in charge were quickly learning by employing trained women cooks and caterers, there was considerable financial savings at a divisional station of many hundreds of pounds per week.

A new source of employment for women, and one being actively promoted in the pages of the Craven Herald, possibly as an advertising 'puff piece' was that of the hospital almoner - even though it required a year-and-a-half of training and would cost the-not-unconsiderable 20 guineas, excluding board and lodging. Specifically for the educated woman, it was very well paid and in early 1916, not overcrowded, but destined, claimed the Herald, to become very popular indeed.

The work provided an opportunity for women to help the poor who often, at their most needy, were utterly ignorant of help available to them. The almoner was the connecting link between the out-patients and the charities. It was also her role to check any abuse of the outpatients department - many men and women even though in a position to pay, still applied for free advice - and also to make sure patients got the best care possible.

Candidates learned the technique of charitable work and the working of the Poor Law. There were also mandatory lectures on social subjects, hygiene, physiology, and economics. There was a fee of 20 guineas, which covered all education, but not board and lodgings, which the woman would have to fund herself.

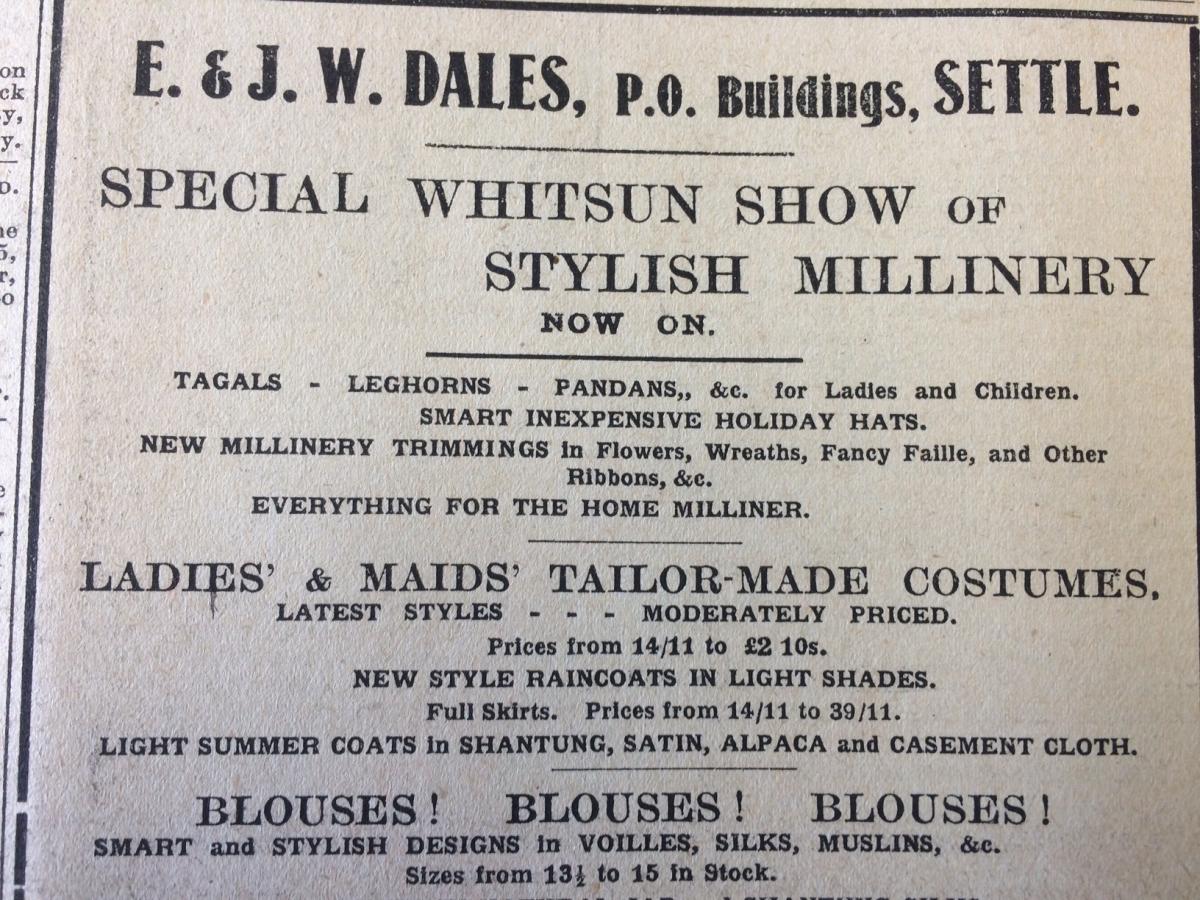

But it wasn't all war, war, war in the ladies column, there were other pressing subjects to discuss, such as what skirts would be fashionable in the coming season. Skirts were steadily assuming crinoline proportions in early 1916 - but reported the 'they had nothing in common with the stiff, ungraceful hoops of early Victorian times'. These full skirts were achieved by means of taffeta petticoats and stiffer at the hips than lower down - so causing the skirt to stand out. Skirts even for morning, country and sports wear were also full, but without draperies of any kind. A silken coat was a must in every women's wardrobe and the vogue for ribbons showed no sign of going away.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here