WHILE the men were away some women did play! And in a "horrible and disgraceful" way, so told the Craven Herald on December 8, 1916, as the death toll on the bloody fields of the Somme battle was still being calculated. Clive White reports.

IN the dock at Skipton Petty Court sessions were Ellen Wilson and Catherine Arkwright, both soldiers' wives. With wartime strait at its toughest, it's understandable they might need to earn an extra copper or two with their men fighting at the front.

But Ellen and Catherine weren't content with a few more hours overtime in the mill, the occasional cleaning job or in munitions. Too much hard work that. So they opted instead to join the oldest profession and promptly opened a bawdy house.

Their enterprise was, needless-to-say, popular with the soldiers on leave who converged on the bordello - a small terraced property in Earby - before heading back to the mud and bullets of Flanders.

How the enterprising duo expected to get away with it is anyone's guess and for a while it looked like they were coining it in? But inevitably, the long arm of the law caught up with them and their day in the dock beckoned.

When it arrived both professed shame at their behaviour, Ellen blaming the war for taking her husband away and Catherine throwing herself on the court's mercy.

When the final sentence came - they each got three months imprisonment and Ellen was told her children would be "taken away from her" - they were grief stricken, bursting into uncontrollable tears.

The Craven Herald reported the whole affair with gusto - the little rural paper rarely got chance to write about such salacious stuff - and the reporter revelled in the opportunity.

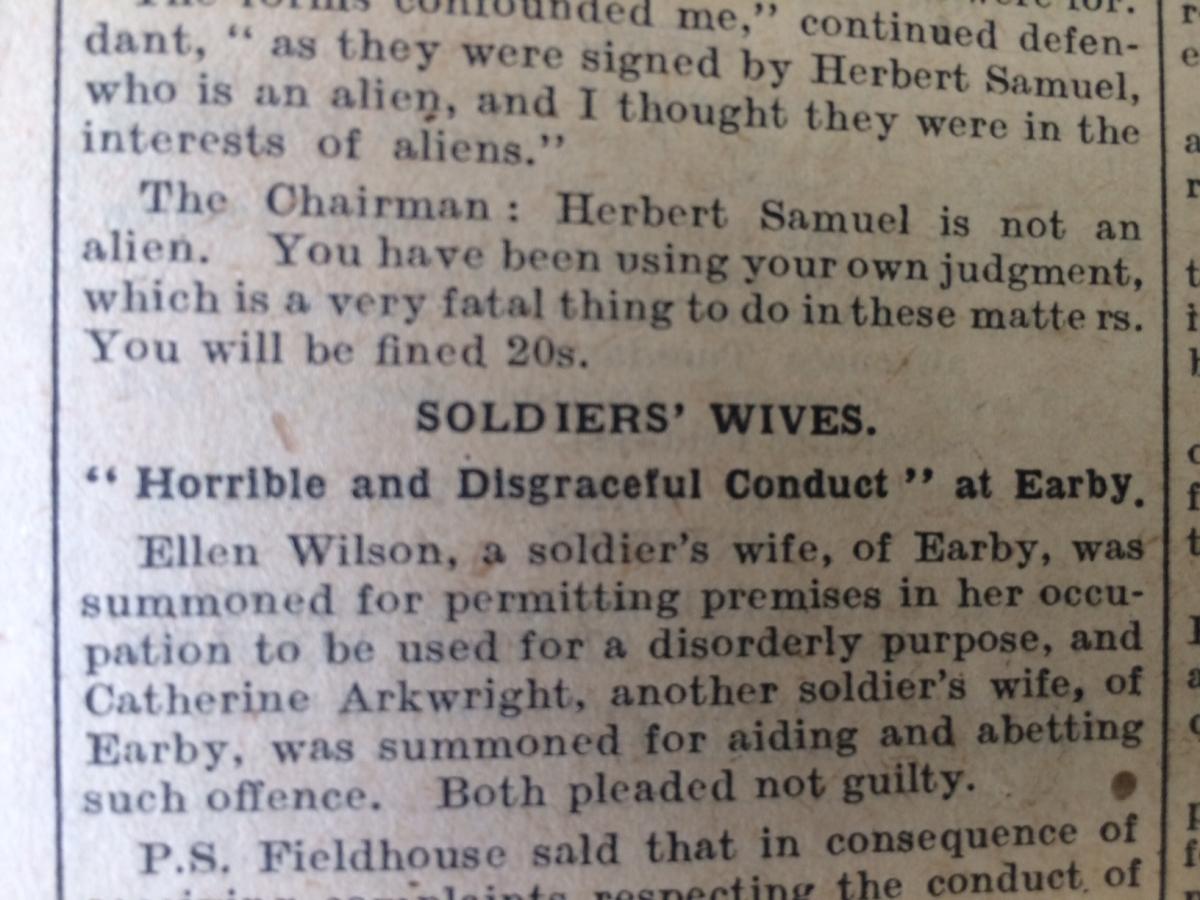

The story was on page two among a string of tales from the Petty Session in Skipton as the courts were known then. The headline read: "Horrible and Disgraceful Conduct."

Ellen was summoned for permitting premises in her occupation to be used for disorderly purposes and Catherine was summoned for aiding and abetting such an offence. Both pleaded guilty.

It seems their enterprise came to light following complaints from neighbours about soldier's loitering outside Ellen's home at Green End Avenue, Earby.

Police officers - Sergeant Fieldhouse and Constable Taylor - were despatched to investigate what was going on

and for more than 90 days kept their beady-eyes open on the comings-and-goings between September 16 and November 25.

Once in court Police Sergeant Fieldhouse relished his opportunity to detail what he had seen happen at the house during the visits of soldiers.

With great pomposity he told the court: "These women have disgraced their homes and themselves" and Ellen "was not fit to have charge of her two children."

It was made worse because she was in receipt of 21 shillings a week from the army authorities and Catherine had a separation allowance of 12 shillings and six pence in addition to the seven shillings and six pence a week from the Midland Railway for whom her husband had previously worked.

When charged with the offences Ellen replied: "I never did wrong until my husband went away. I deserve to be thrashed. It's the drink."

And Catherine responded: "Oh dear me, my husband will never come to me again. I have done wrong and I admit it."

As the case progressed two neighbours were called as witnesses and spoke of seeing men visit Ellen's house during "the day time and at all hours of the evening."

One claimed that the "wrong-doing" had been going on for 12 months and had got worse since Catherine went to live with Ellen the previous June. It had got so bad that other neighbours were considering leaving the area.

In summing up, long-serving Chairman of the Bench, J.W. Morkill, who had praised the officers on their assiduous pursuit of the crime, told the women: "You have behaved in a most horrible and disgraceful way.

"Your husbands are away fighting for King and country and left their honour and families in your hands and you have betrayed it. You have made your house a blackspot in the place and a blot on the whole community."

Mr Morkill also remarked that it was now time for Ellen's children to be taken away from her.

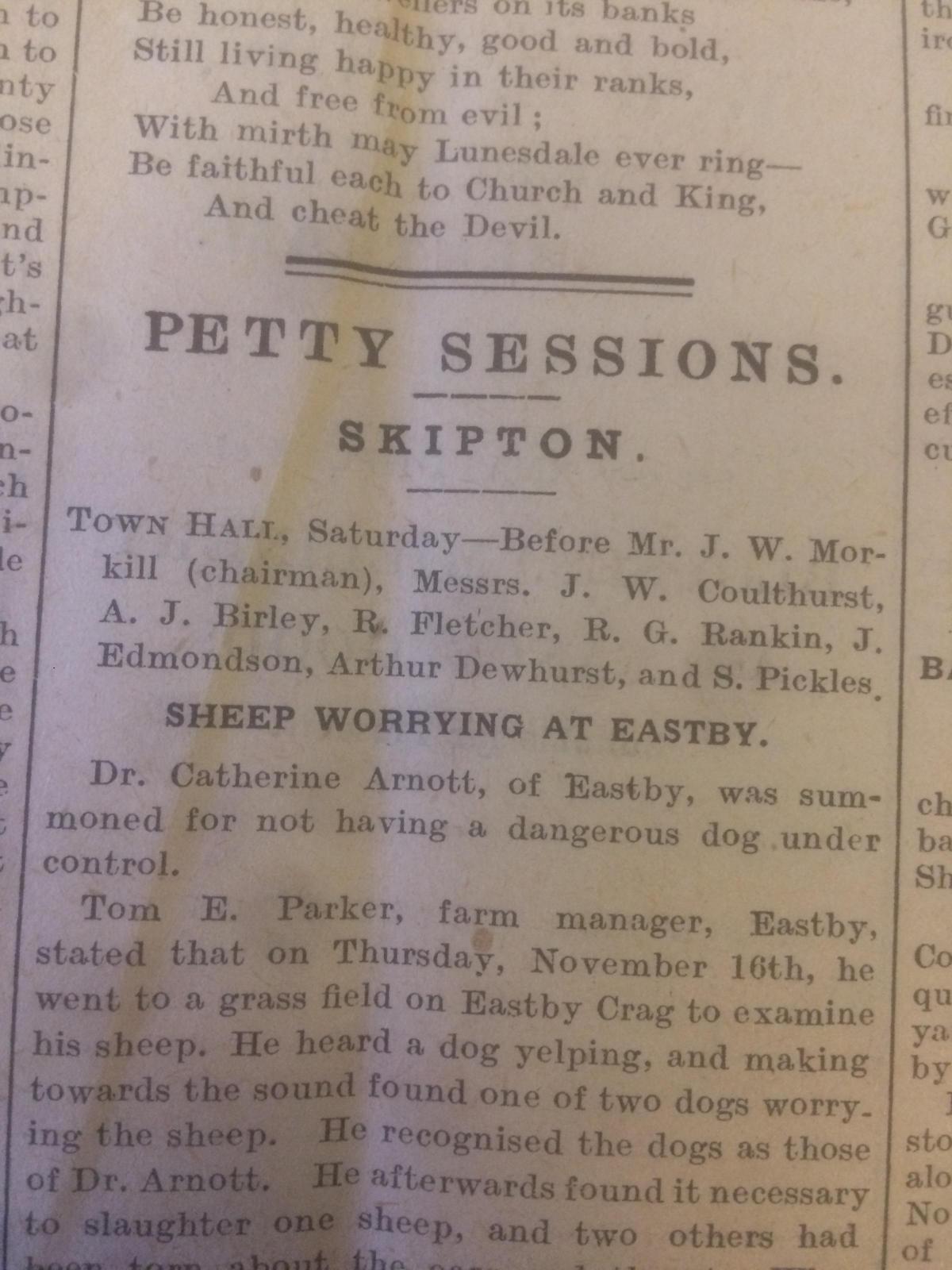

The case was held on Saturday, December 2, 1916, at Skipton Town Hall, and was among a batch of relatively mundane offences including sheep worrying, six breaches of the wartime lighting order, using obscene language and assault on a special police officer.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here