My peaceful vigil in the yard of St Leonard’s Church, Chapel-le-Dale, a few years ago was temporarily shattered by the roar of a tractor engine. I saw an ordinary tractor on an extraordinary mission – to deliver, on a scoop, over the church wall, a large piece of stone.

It would form part of a memorial: a poignant reminder of over 200 railway folk – men, women and, unhappily, many children – who died in the 1870s during the construction of the Settle-Carlisle railway.

So many were interred here in “railway time” that the churchyard had to be extended.

St Leonard’s Church, formerly the chapel for “Ingleton Fells”, presides over my favourite tract of Yorkshire – a silent, tucked-away area where one tends to talk in whispers.

A boggart is said to live in the pothole behind the church. In old woodland, trees and stone are lagged with moss and in the twilight you would not be surprised to see a troll, the diminutive figure of Norse folklore.

Attached to a wall inside the church is a memorial to those who died when the Midland’s first-class, all-weather route was being made using the north-south valleys of North Ribblesdale and Edenvale, with a lump of high Pennines in between. The memorial was put in place on behalf of the Midland and fellow workmen.

Only two gravestones with Settle-Carlisle associations are to be seen. There is an inscribed standing gravestone near the far wall, as you look to the left of the path that passes under a lych gate and makes a bee-line for the church door. This gravestone commemorates James Mather, the proprietor of a beerhouse called the “Welcome Home”, situated at Batty Wife Hole, the largest of the shanties erected during “railway time” for the hundreds of men, women and children quartered hereabouts.

Mather catered mainly for the dry throats of navvies. He was, by all accounts, a decent type. His death was caused by a gallant deed – that of trying to stop a bolting horse by grabbing the reins. He was dragged under the clattering hooves and pounded to death.

The second inscribed gravestone is seen on the right after you have passed through the lych gate at St Leonard’s. Notice a substantial, horizontal gravestone with a stone cross at one end. This is the last resting place of Job Hirst, a native of Huddersfield, who achieved fame through the Settle-Carlisle railway.

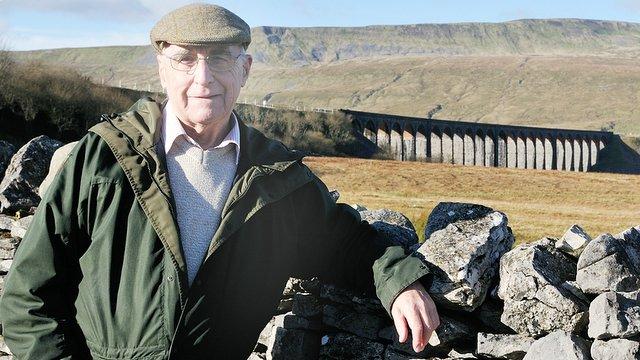

It was he who, designated as a “railway sub-contractor”, supervised the early stages of the construction of Ribblehead viaduct. This stupendous feat of engineering consisting of 24 arches, carries the line on a 1 in 100 gradient, across Batty Green, curving gently towards Blea Moor, through which a railway tunnel would be driven.

Hirst had begun a working life as a mason. He graduated to viaducts, which in his early years were usually referred to as “large bridges with many arches”. When I first became interested in Job, the lettering on the gravestone was clear-cut. Now much of it has been eroded by rain, wind and frost.

For two years, the ambitious Job left his wife, Mary, and their sons at home, having secured work on the Bombay-Poona railway, the first railway on the sub-continent of India. In the early part of the Railway Age, workers reacted to wanderlust. Job, returning to England, became sub-contractor at Ribblehead, on the Settle-Carlisle.

In his railway work, Job initially had a team of 60 masons, mostly of Welsh origin, and labourers. The number rose to 100. The turnover of workers was about eight a day. Good wages were paid. The foundations of the viaduct were set 25 feet below ground. Local people were to persist that the viaduct was built on wool. Hardly. Concrete was used. The wool story may have related to fleeces being used to prevent a seepage of water into the foundations during the early stages. Or perhaps the reference to money borrowed from the wealthy wool merchants of Bradford by a hard-up Midland Railway Company. Job and his colleagues had to find limestone of the right degree of hardness. A good source was found in Littledale, in the bed of what, at times of heavy rain, was a lively beck. Normally, the flow could be kept under control. A steam pump improved the drainage. Water was diverted along an aqueduct.

Altogether, about 30,000 cubic yards of rock were obtained, dressed, transported by tramway to the site of the viaduct and raised into position using a steam-crane. Local limestone was unsuitable for making durable mortar. The kiln on Batty Green had been well-used by farmers, who spread burnt lime on their best land to keep it sweet, but the ideal type of lime was imported from Leicestershire. A 10hp engine was used to mix the mortar needed to bind the stones of the viaduct.

Back to Job Hirst, sub-contractor. What happened then was contained in a letter I received from a granddaughter living in the United States – an appended account of his last days had been composed by Gwenliian, Job’s daughter.

One day, he visited Ingleton by horse and trap to collect money for the wages of his employees. There were flurries of snow in the air. On his return to Batty Wife Hole, at Ribblehead, he was set upon by thieves. They took the wages, also his gold watch. The hapless Job was left unconscious at the roadside. Job recovered and groggily managed to clamber on to the horse-drawn trap, having found his treasured gold watch. It had been left hanging by its chain in some bushes.

Job had to rely on his horse to find the way home, which was a substantial hut, No 2 Batty Wife Hole. His wife, plus four sons and a daughter, were shocked by what had taken place. Mary, the wife, unwisely plied him with port. He was tucked up in bed. When she awoke next morning, Job lay dead at her side.

* Thunder in the Mountains, by WR Mitchell, is published by Great Northern and costs £18.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here