by Dr Bill Mitchell

IN the autumn of 1869, the peace of Chapel-le-Dale was stirred by a traction engine that was hauling a four-wheeled van from Ingleton to Ribblehead. It was rumoured that the journey had begun in London. The van, grandly known as The Contractor’s Hotel, provided accommodation for engineers and their helpers at what would become noted as the setting for Ribblehead Viaduct.

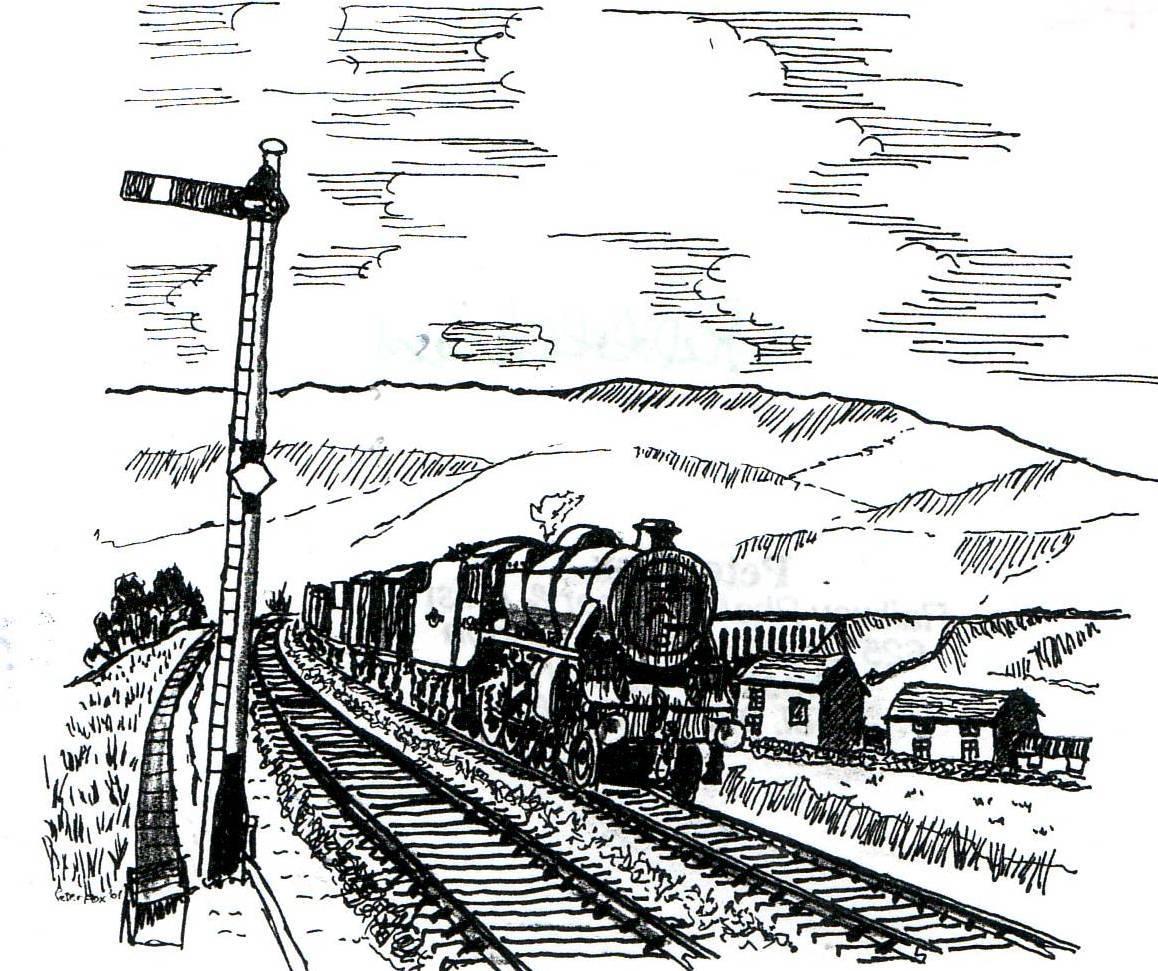

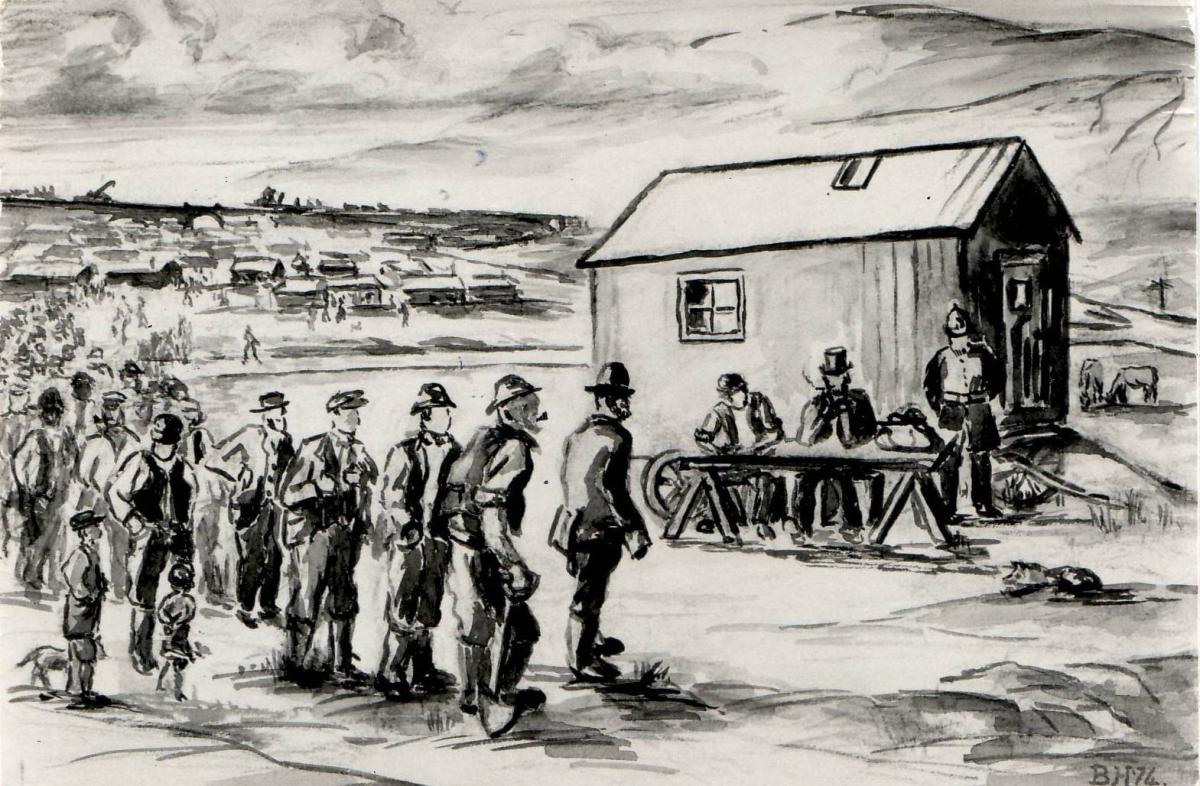

Ere long what had been a quiet area, haunted by grouse and sheep, became speckled with industrial buildings as work on the Settle-Carlisle developed. Most of what is written about the construction of the Settle-Carlisle is work-wise.

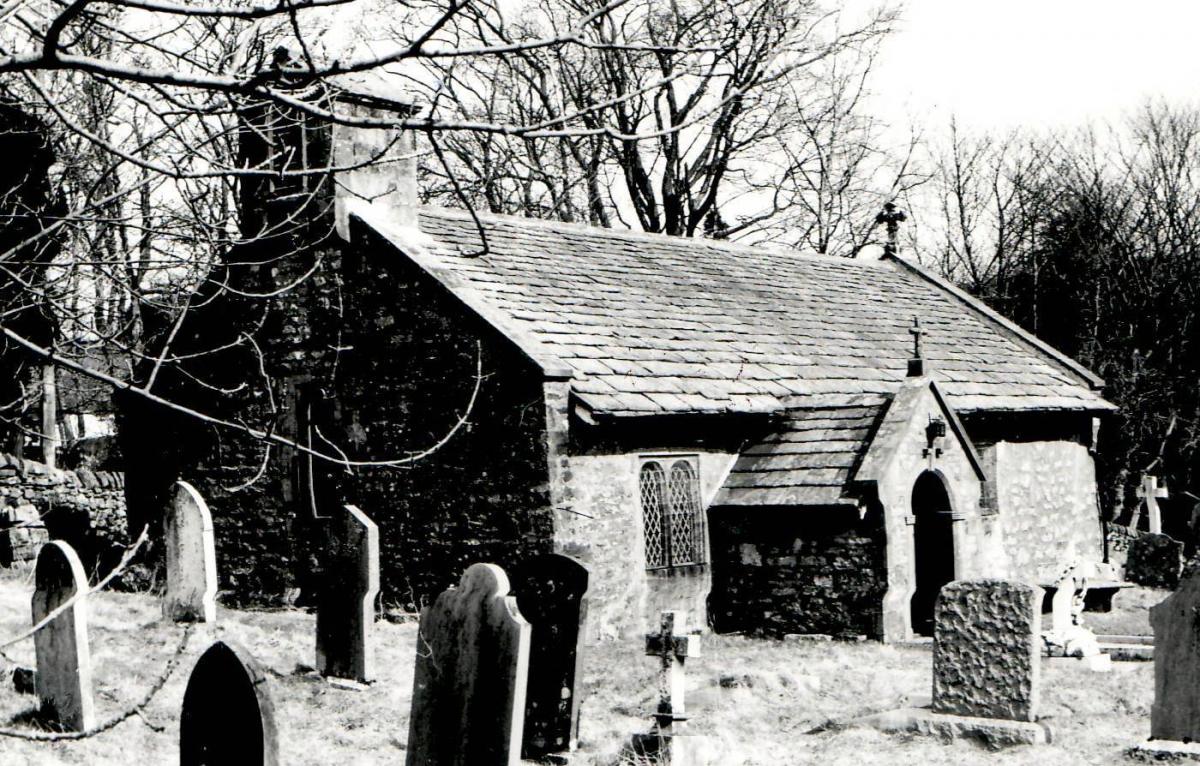

There were, indeed, moments of pleasure and also, alas, sad days when funeral parties, heads bowed, made their way to St Leonard’s Church in Chapel-le-Dale. Over two hundred railway workers, wives and children were interred here in the 1870s.

Life in the shanty huts at Ribblehead could be lively. A shanty hut, holding some of the families of men who were building an enormous railway viaduct, usually had three rooms. One room was for the family, another for navvy lodgers and a central space used for communal activity, such as meals.

An insight into shanty activity is provided by what was purported to be a true account that appeared in Chambers’s Journal. The event was said to have taken place in the home of the so-called Pollen family. Mrs Pollen had her moments of joy and also of anger, such as when a chap known as Wellingborough Pincer became “an incorrigible and indomitable nuisance”. She had the knack of throwing him out.

On a day when the family festivities were to take place there was a rapping sound on the inner side of the door that led to the navvy quarters. Mother Pollen – as she had become known – shouted “Come in”. The man who entered was a stalwart navvy, blushing from ear to ear but with a twinkle in his eyes – dark eyes. He would subsequently be referred to as Big Black Eyes.

Speaking on behalf of fellow lodgers, he “craved humbly that they should be admitted to participate in the festivities of the evening.” It was agreed. The navvies trooped in, sitting on the extreme edge of a wooden form.

Mrs Pollen made some wine available. Black Eyes played a lively tune on his fiddle. He distinguished himself when dancing took place to an Irish jig, playing the music and dancing simultaneously. The beer-pale was replenished. Ladies were radiant with good humour and enjoyment. Tom Bugin sang My Pretty Jane, which was a popular song of the day. The evening passed hilariously – until the Wellingborough Pincer arrived. His poor conduct led to what was termed a shindy. Mrs Pollen pinioned the Pincer with a vice-like grip and bundled him towards the door. The sound of a thud to indicated her success.

James Tiplady was appointed by the Midland, in collaboration with the Bradford City Mission, as a Scripture Reader for Contract No 1. An especially sad task was to officiate at funerals. When Annie Wall, newly arrived in the area, died through an accident while travelling with an aunt on a tramway train that became derailed. Tiplady gave the oration at a funeral service held in the family hut at Sebastopol. He accompanied the mourners when the body was borne in a small cart to the yard at Chapel-le-Dale.

Chapel-le-Dale was a valley so named because of its attractive little church which is prettily situated and was described by Southey in his novel The Doctor. Workers showed great sympathy to each other in sickness or death. The churchyard at Chapel-le-Dale was extended on 1871 through a gift of land by Earl Bective. It was necessary on account of the terrible havoc made, by smallpox, among the inhabitants at the new railway work on Blea Moor.” Over thirty people who had died of smallpox lay in the old burial ground.

Inside the church is an inscribed memorial to those who died when the Settle-Carlisle was being constructed.

The setting of the church, which is situated a short distance from the main dale road, is attractive and with mighty Ingleborough dominates the dale.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here