HEBDEN author David Joy explains why he has found the life and times of lead miners in the Dales such a fascinating subject for a new book

THE ITV drama Jericho, portraying navvy life during the building of the great Ribblehead viaduct, has been well received. The sets are both impressive and accurate, largely because photographs were taken of work in progress in the mid-1870s. If only those behind the camera had at the same time focused their attention on lead miners at work, they could have provided the backdrop for a drama of even more epic proportions. It would be on a par with the classic Poldark saga of Cornish tin miners.

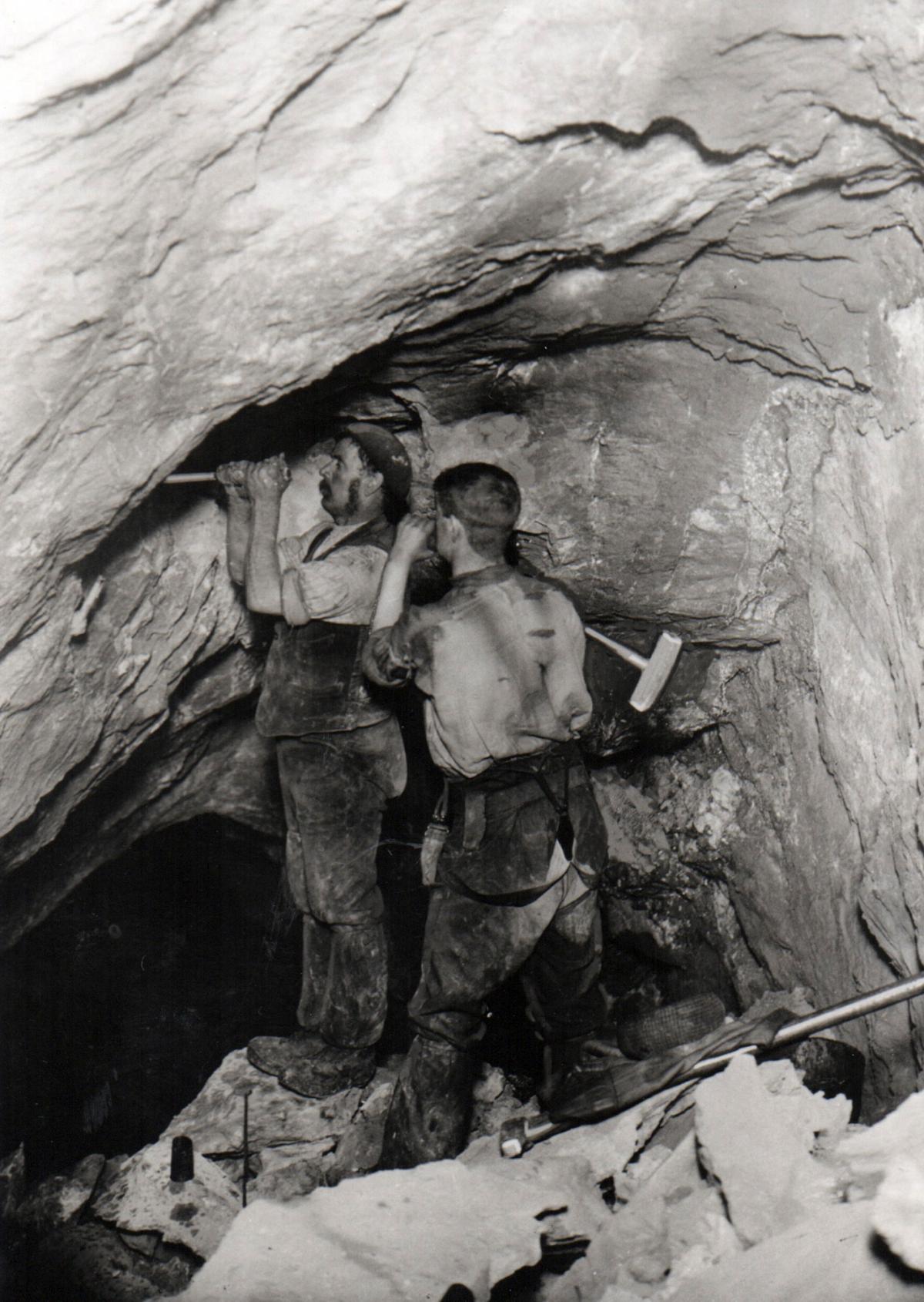

Lead miners faced even greater rigours than the railway navvies, toiling underground by candlelight in pursuit of supremely rich veins of lead. It was a quest capable of producing untold wealth but so often led to poverty and early death in pursuit of an elusive dream. While men wielded pick and shovel in the darkness, women and children as young as eight worked in all weathers sorting the lead ore on exposed dressing floors.

At a considerable distance were wealthy mine owners, who added what is now an ever popular ‘Upstairs - Downstairs’ element to it all. Small wonder that it is the nearest the Dales has ever come to a gold rush. Lead is so heavy that it does not take much to weigh a ton, which at the industry’s mid-19th century peak fetched over £20 – the equivalent of more than £2,000 in today’s money.

Much has been written about technical aspects of lead mining but remarkably little on the miners themselves. Hence the irresistible urge to write the newly published Men of Lead: Miners of the Yorkshire Dales. Photographs of men at work have indeed proved elusive, although a few were taken on Craven Moor close to Stump Cross Caverns.

Grassington was the heart of mining in the Craven Dales. Here the mineral rights, long exploited with little zest by the Cliffords of Skipton Castle, passed by marriage to the Dukes of Devonshire. The 5th Duke found himself one of the richest and most extensive landowners in Britain, but did little to make the most of reserves of lead on Grassington Moor.

His favourite occupation was whiling away the night by drinking and gambling in London clubs, parting with huge sums in the company of his infamous first wife Georgiana. Star of the best-selling book and successful film of recent times, she somehow managed in 15 years to run up gaming debts that in present-day terms amount to over £6.5 million!

Fortunately throughout much of this period the dukedom had a fabulously rich copper mine at Ecton in Staffordshire. Then this suddenly failed and attention turned to maximising revenue at Grassington. It was a slow process, which only achieved success when the 6th Duke brought in John Taylor, a mining engineer and genius, to act as his chief mineral agent. It was the equivalent of today’s international headhunt for a chief executive, and he soon transformed the whole mining field.

Grassington became a lively and very crowded village. One obvious change was the provision of chapels, reflecting the fact that the exuberance of non-conformity appealed to the independent spirit of miners. The Church of England had locally lost touch with its parishioners, a situation not helped by the 40-year reign of the rector of Linton, the Rev Benjamin Smith, a Latin and Greek scholar known as one of best dancers in England but regarding his flock as ‘baptised brutes’. His views were shared by the Rev Thomas Dunham Whitaker, author of a monumental History of Craven, who saw miners as ‘the mere trash of a church yard’.

High noon for Grassington came in the 1850s when almost half of its 1,138 inhabitants were aged under 21. It was a wonderfully self-sufficient community, especially as regards craftsmen supplying essential footwear for miners and their horses. There were six shoemakers, a clogger, three cordwainers and nine blacksmiths. Other key occupations included five tailors, a barber, four butchers, five bakers and ten carriers.

Yet there were soon signs that mining had passed its peak. The advent of steamships enabled ore to be brought in from Spain at a much lower cost and once it started the decline was swift. The mines closed in 1882 and there was little alternative employment. Families had to move to the industrial West Riding or Lancashire, or emigrate to North America and Australia. Nine years later Grassington saw its lowest-ever population figure of just 480. Men of lead, who had achieved so much for so little, were there no more.

* Men of Lead costs £12.50 including postage from Paradise Press Ltd, Scale Haw, Hole Bottom, Hebden, Skipton, BD23 5DL. It can also be purchased at all National Park Centres or online at retail@yorkshiredales.org.uk. And £1 from the sale of each copy is being donated to the Yorkshire Dales Society.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here