Take a trip along the Settle-Carlisle line today and see for yourself the staggering amount of engineering which was needed to create what we in Yorkshire consider a national treasure. Hannah Kingsbury, historic environment apprentice with the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority, spent a day on the line last autumn. She writes on the YDNPA blog of her experience while enjoying a piece of living history along the longest conservation area in the UK.

THE construction of the railway has been described by some as one of the most extraordinary feats of Victorian railway engineering, and by others as one of the most foolhardy.

The railway is testimony to a great age of endeavour. The engineering achievements of the line are further enhanced by striking buildings and trackside structures. There are 14 tunnels and over 20 viaducts along the line.

These buildings and their relationship with each other and the surrounding landscape represents a group value. This has been recognised and designated as a Conservation Area.

The designation (in 1991) covers the whole railway, over 70 miles of track, as well as all associated historic structures.

There is a coherent design of identity the length of the route – it is characterised by typical JS Crossley structures (he was chief engineer at the time), along with Midland’s systematic approach to the design of stations, signal boxes and other ancillary structures.

There are 11 stations that are still operational. This includes Dent, which is the highest main line station in England (at 1,150 feet above sea level).

The railway was built across some of the most difficult terrain in England. It cost £3.8 million (nearly £200 million in today’s terms) and took six and a half years to construct.

The line was built by the Midland Railway, one of the most powerful and wealthy of the Victorian railway companies.

Based in Derby, its wealth had been generated by the coal it transported from Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire.

In 1868 they reached London – then they turned their attention northward. They wanted a share of the lucrative London to Scotland passenger traffic, but did not want to have to send its traffic over the lines of its rival west coast company - London and North Western Railway.

As a result of attempts to come to deals with rivals failing, a Bill was introduced to Parliament in 1865 to enable Midland to build new routes. The Bill went through, despite opposition, but nothing was done for several years.

In 1869 Midland struck a deal with London and North Western Railway, probably because the projected cost had begun to scare the Midland’s shareholders.

Together they tried to get a Bill put through abandoning the line, but this was refused. Parliament at the time was fearful of ‘Railway Monopoly’.

The initial idea for the Settle to Carlisle line was to connect the journey from London to Scotland without changing train company.

This was the last navvy-built railway line in the country. Huge quantities of men, both skilled workers and labourers, were brought in from all over to the country to work on the railway.

At its height, over 7,000 men were working on the project.

The major construction work took place at the Ribblehead section with its impressive viaduct and Blea Moor tunnel. At one time there were about 2,000 men working on this section alone.

This led to sprawling shanty towns being built at the area that were overcrowded and unhygienic. The settlements were called Sebastopol, Jericho and Batty Green.

The line opened for passenger traffic in May 1876, providing luxurious travel to Scotland in Pullman coaches. After all the time, manpower, engineering and money, it is likely that it never made a profit.

The construction also had a high human cost – a large number of workers and their families died from accidents and diseases.

The Batty Moss viaduct, at Ribblehead, is perhaps one of the most iconic along the line. It is certainly the tallest, 104 feet at its highest point, and has an impressive 24 segmental arches.

Many have argued that the Settle-Carlisle line is one of the most scenic railway journeys in England. The route forms a coherent and outstanding historic railway landscape of national significance.

The combination of the natural beauty and bold man-made structures still provides drama for both rail passengers and people roaming the countryside.

The line was engineered to follow the natural pathways through the hills of the Pennines.

The relationship between the railway and the landscape is determined by very exact requirements of railway engineering. For instance gradients are limited by the power and speed of the trains. These limitations require man-made interventions – in the form of cuttings and embankments.

The line from Settle to Carlisle was determined by the strategic need to get over the watershed. This defines the alignment of the railway relative to the landscape at a localised and wider level.

It is the relationship between these civil engineering works and the natural form of the land that creates the distinctive character of the area.

David Butterworth, chief executive of the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority, said the saving of the line was significant for tourism in the Dales.

He said: "The reprieve for the Settle-Carlisle line was a huge moment for the Yorkshire Dales National Park.

"The line brings considerable economic, transport and environmental benefits to the Park.

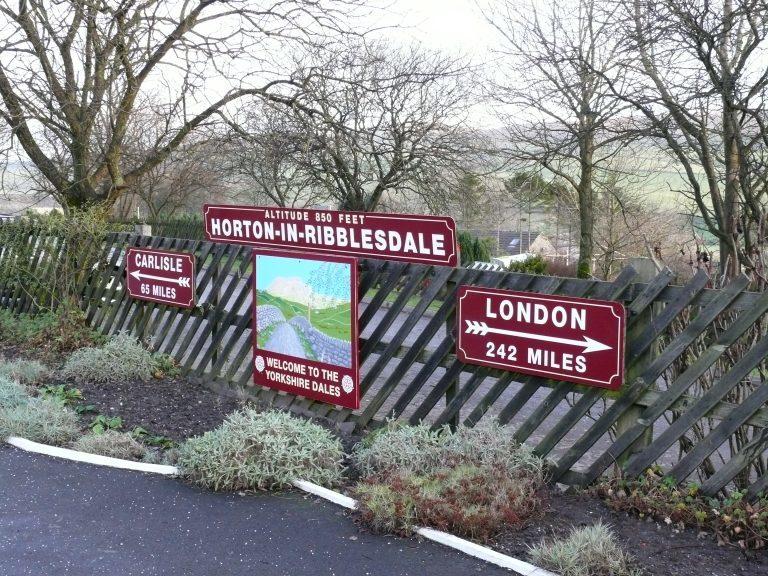

"Five stations lie within it – Kirkby Stephen, Garsdale, Dent, Ribblehead and Horton-in-Ribblesdale – while Settle station lies just outside the boundary.

"It means that residents can have days out to market towns while tourists can visit, without the need for a car.

"It’s a heritage attraction, too, as well as a working railway; the line’s marvellous infrastructure has become an integral part of a landscape loved the world over.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here