IT was a bleak time for German prisoners of war being held in Skipton's Raikeswood Camp during WW1 when an outbreak of Spanish flu claimed a number of casualties.

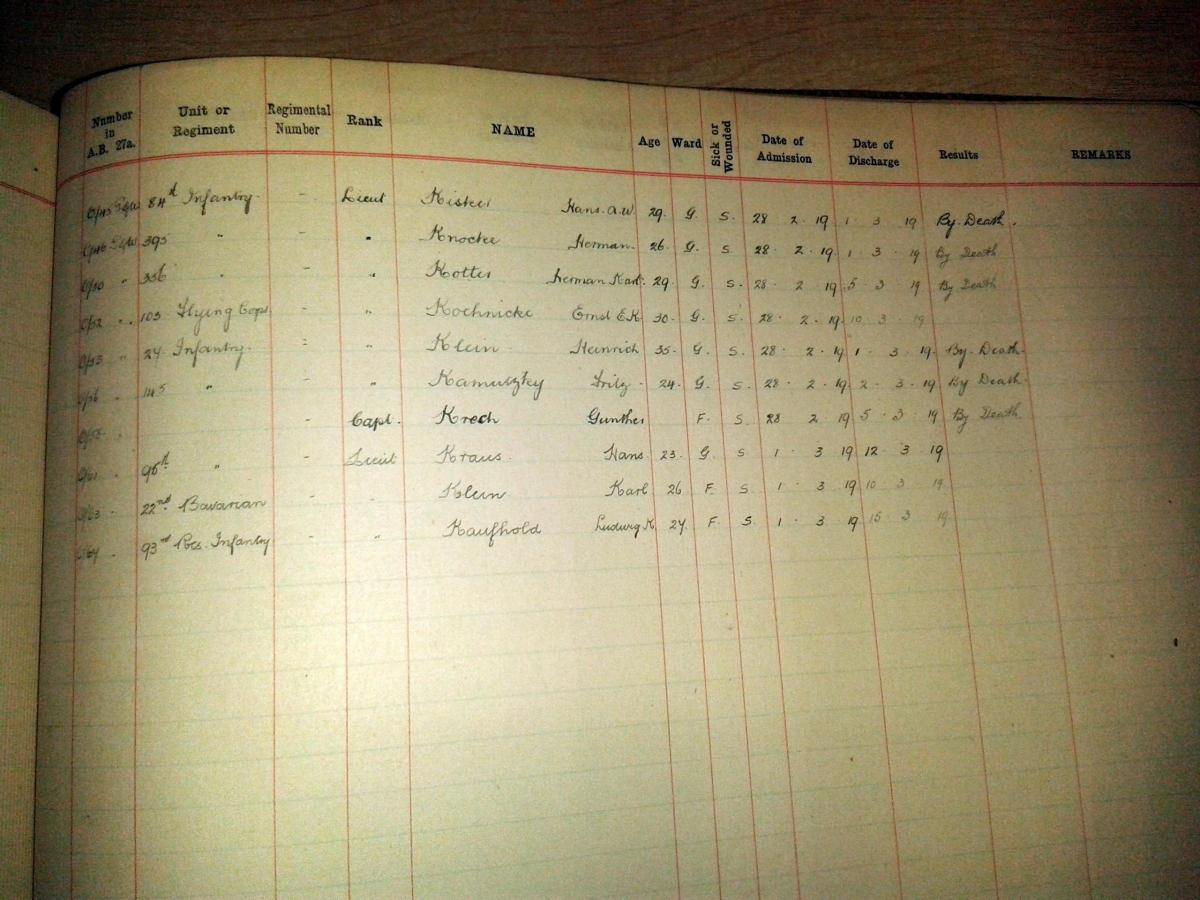

In early 1919, 47 of the German prisoners died; 42 of them died in Morton Banks hospital where they were being treated and another five died in the camp.

The funerals took place at Morton Cemetery, Keighley, where the men were then buried. The prisoners designed an elaborate memorial to their deceased comrades which was constructed in the cemetery. In the 1960s the graves were moved to Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery and the memorial was taken down.

The impact of the outbreak is detailed in a book, Kriegsgefangen in Skipton, which was written from smuggled diaries kept by the prisoners and published into a book in 1920.

That book is currently being translated into English by a team led by Anne Buckley, a lecturer in German at the University of Leeds.

Extracts from the book read:

On February 12 five orderlies fell ill with influenza. The sick were treated in their barracks at first. Only when their condition became more serious were they taken to the camp hospital. The illness soon spread further among the orderlies, and on February 15 it spread to the officers. It would develop as follows: after an incubation period of two to three days, during which the symptoms were a lack of appetite and tiredness, a fever would suddenly break out, forcing the patient to take to his bed. The fever would be accompanied by fits of shivering, high temperature and a headache. The patient would suffer from constipation and lack of appetite, he would feel weak and appear apathetic. Additional symptoms were coughing, nosebleeds, backache and aching limbs, and occasionally an ear infection. The fever would peak on the 4th or 5th day when the crisis point was reached. In most cases the temperature would gradually fall from this point and the patient would begin to recover. However, lung damage and heart problems were often lasting consequences. Unfortunately, complications arose in many cases due to tissue and nerve damage. In such cases the fever did not abate and pneumonia and heart problems ensued. It was very noticeable that almost all of the sick, and especially the most seriously affected, were no older than 30.

The camp took on a sombre air. All loud activity ceased. Classes and lectures were suspended. No singing, no music sounded through the Old Mess; no creative works were performed. The usual noisy comings and goings of the mess rooms ceased. The few who were still healthy now ate in the Old Mess at a few sparsely occupied tables and went about the camp with tired faces, strained by worry about their own fate. One constantly saw stretcher bearers everywhere; we asked reluctantly but with heartfelt concern which comrade lay under the blanket. Vehicles rattled their way through the camp gates, stretchers were loaded in.

With fear and hope in our hearts, our eyes followed the departing vehicles. Indoors, in the sickbays, bed by bed, our comrades lay in feverish delirium: strong men, old soldiers prepared to bear anything, even death; now frightened men with shattered nerves, preoccupied by thoughts of death. One asked for a rosary, another, a teacher, taught his pupils in the night hours, yet another leapt out of bed in his fever thinking his mother was waiting for him outside.

One, the last of four fallen brothers, made his will. Others, in their confused minds, were standing in battle, leading their men with loud commands or quietly-spoken orders. Some lay under the covers pale and apathetic; some readied themselves quietly for the final journey. What would we have done without you, our healthy comrades, in those hardest hours, united in providing selfless aid day and night? You sat by our bedsides to comfort us, you straightened the sheets and positioned the pillow with your faithful and, let’s face it, clumsy hands, you quenched our feverish thirst, you wrote our letters home, you willingly took upon yourselves even the most difficult and unpleasant sickroom duties. And you did this quietly and gladly.

In the darkness of night you sat like faithful guardians, wrapped in your greatcoats, among your many patients, and when someone called out, you were always on hand, helping with loving care. If we had not had you, how many more would be lying there in that Keighley cemetery? And also you few faithful orderlies, who weren’t yourselves laid low, during those difficult days, you dealt with the care and transportation and all the other tasks, all performed out of your great love of helping others with all your might.

The English authorities did nothing to prevent the illness spreading. All they did was to prescribe constant fresh air, and the commandant allowed all the officers the opportunity to go walking both morning and afternoon.

The English camp doctor could no longer fulfil what was expected of him. As no medical preparations had been made, he faced insurmountable difficulties. The camp hospital was soon overcrowded so the sick had to remain lying in their barracks alongside the healthy. This was probably the main reason why the disease continued to spread. As the English authorities did nothing to establish proper sickbay organisation, 10 barracks formerly used as dining and living quarters were converted into makeshift sickrooms at the instigation of the German camp management.

On February 18 the English military doctor Captain Melbourne arrived here from Ripon with 11 English and four German medical orderlies. But even these reinforcements were not enough because of the absence of any organisation. Some of the subordinate staff were really quite negligent in their duties. Each individual patient was only seen by the doctor once a day unless an extra visit was requested. Temperatures were only measured once a day; for this purpose the thermometer was stuck into the patient’s mouth. It was observed that the same thermometer was used for several patients without cleaning it first. On several occasions the medical assistants also mixed up the sick notes of individual patients so that incorrect information was recorded. There was little examination of heart and lungs: the entire treatment was limited to taking temperature, stimulating bowel movements and distributing cough medicine. The shortage of bedpans was a great deprivation; the sick were obliged to find their way to the primitive outdoor latrines even in cold, rainy and windy weather. It was clear that some of the sick suffered a worsening of their condition as a result of this. Bed linen was only changed at our insistence.

No special diet was provided for the sick at first; both sick and healthy were fed horsemeat and beans. Only after energetic representations by the mess management was there any improvement in provisions. The commandant took it upon himself to allow the canteen to order in fresh meat (500 English pounds weight for 550 officers), eggs, milk and canned fruit, in addition to which we received an extra four ounces of bread a day and a cup of tea with rum with our evening meal.

In spite of the overcrowding of the camp hospital with seriously ill patients and the large number of seriously ill patients left lying in their barracks, the English camp administration undertook the necessary steps for the seriously ill to be moved to hospital only after we demanded it. The town of Skipton refused to place their ‘military hospital’ at our disposal giving the feeble excuse that it was actually the workhouse and it would not be permissible to deny access to its rightful occupants. Eventually the War Office gave permission to accommodate the sick at Morton Banks Military Hospital near Keighley, provided that beds were vacant there. At first, permission for this had to be sought from the War Office for each individual patient; each application had to find its way through four or five departments before a reply arrived. The sick were taken to hospital in motor ambulances and transfers were often subject to long delays due to their unavailability. It was not until they were able to provide a whole building at the hospital especially to accommodate the German patients that all the seriously ill were taken to Keighley.

Morton Banks Hospital, owned by the town of Keighley, had been designated a war hospital since the Somme offensive. The first patients from our camp were admitted on February 20. Eventually two buildings were allocated to the German patients. Sadly, access to proper hospital treatment came too late for many of the sick, in addition to which they were all transferred from the camp without medical records of any kind so that the doctor had no indication of the previous course of the illness.

Most of the patients themselves were in no condition to supply any details. The doctor made his rounds three or four times a day. Three nurses and two medical orderlies were on duty in each of the three wards during the day, and two nurses and two orderlies at night. One great difficulty in the care and treatment of the sick was the impossibility of communication between patients and carers. At the request of the senior German officer, one of our comrades was therefore sent to the hospital as an interpreter. He reported on his experiences and observations stating: "I was present for all of the doctor’s rounds. In my estimation, the medical treatment was quite excellent."

The food ration for the seriously ill consisted of fresh milk with whisky or brandy (a ward with 33 patients received 45 litres of fresh milk per day). Patients on the road to recovery received bread, butter and tea in the morning, fish, potatoes and rice pudding at midday, bread, butter, jam and tea in the afternoon and cocoa or beef tea in the evening. Patients free of fever received bread, bacon or ham, and tea in the morning. The cost of board was three shillings per person per day.

Due to overcrowding the hospital could spare no further buildings and, as the rooms already allocated to us were not sufficient, quite a number of our patients had to be accommodated on the very draughty verandas. Some of the sick were even sent back to camp, still in a very weak condition, due to this lack of space. Whereas the nurses did their best out of kindness and tireless conscientious care, some of the medical orderlies showed their aversion to us Germans by their insolent behaviour. These people were relieved of their duties as soon as a complaint was made. Recovering officers were allowed to go walking in a particular section of the hospital gardens on giving their word of honour. A protestant and a catholic priest frequently visited the sick.

Craven Herald reports:

Feb 28, 1919 German Prisoners Succumb to Influenza.

"A number of serious cases of influenza which have occurred at the Skipton Prisoners of War Camp have been transferred to the Keighley War Hospital, and already there have been six deaths from the disease among the prisoners. On Tuesday five soldier orderlies to the officers interned at Skipton, whose deaths have taken place at the Keighley Hospital, were buried at the Morton Cemetery. The services were conducted by Captain Peck (chaplain to the hospital) and the Reverend Father Holohan (St. Anne’s Church, Keighley) and a firing party attended from the camp. A number of wreaths were placed on the grave, but these bore no indication of their senders.”

March 7, 1919 “Influenza not abating.

"At the Raikes Camp the epidemic is still being experienced in a virulent form amongst the German prisoners, but having regard to the fact that there are several hundreds of suffers the mortality has not been large. So far there have been about 50 deaths. The most serious cases have been removed to the Morton Banks Hospital, Keighley, where most of the deaths have occurred.”

On the occasion of a visit to the cemetery in which our dead were buried, we took the opportunity to express the camp’s gratitude to the head of the hospital in person for the excellent care and treatment received by our sick. It must be mentioned however that the senior consultant was called to account by the hospital management board for this friendly treatment of the German officers. He is said to have given the honourable gentlemen the only proper answer, that as a doctor he recognised neither Germans nor English, only patients.

Of the 546 officers and 137 other ranks interned in the Skipton Camp, 324 officers and 47 men became ill. Of these, 74 officers and 17 men were taken to the hospital. 32 officers and 10 men died there, and five officers died in the camp.

During the epidemic a representative of the Swiss Embassy had visited the camp and when he returned on July 5 he told us that the Swiss Embassy had forwarded a report on the influenza epidemic to the German government on the basis of information given to them by the British government. We expressed our amazement that we had not previously been consulted about this, as we would certainly have had some grievances to air. When we named some of them, he told us that conditions were much worse in the camps in France.

We laid our dear departed comrades to rest in the cemetery in Keighley. In order to pay them our last respects, a detail of 10-14 officers and men were driven from our camp to Keighley on the day of each burial.

We marched from the hospital to the cemetery, some distance away, in solemn funeral processions. The English guard of honour, led by an officer, proceeded at a slow march ahead of the hearse bearing two coffins; we German comrades followed behind.

The coffins were lowered into the grave to the accompaniment of the English troops’ impressive ceremony; in silence we raised our hands to our caps in a farewell salute.

The English military chaplain spoke words from the Scriptures and said prayers full of comfort and faith, and concluded with a benediction for those whose bodies we were laying to rest in foreign soil.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel