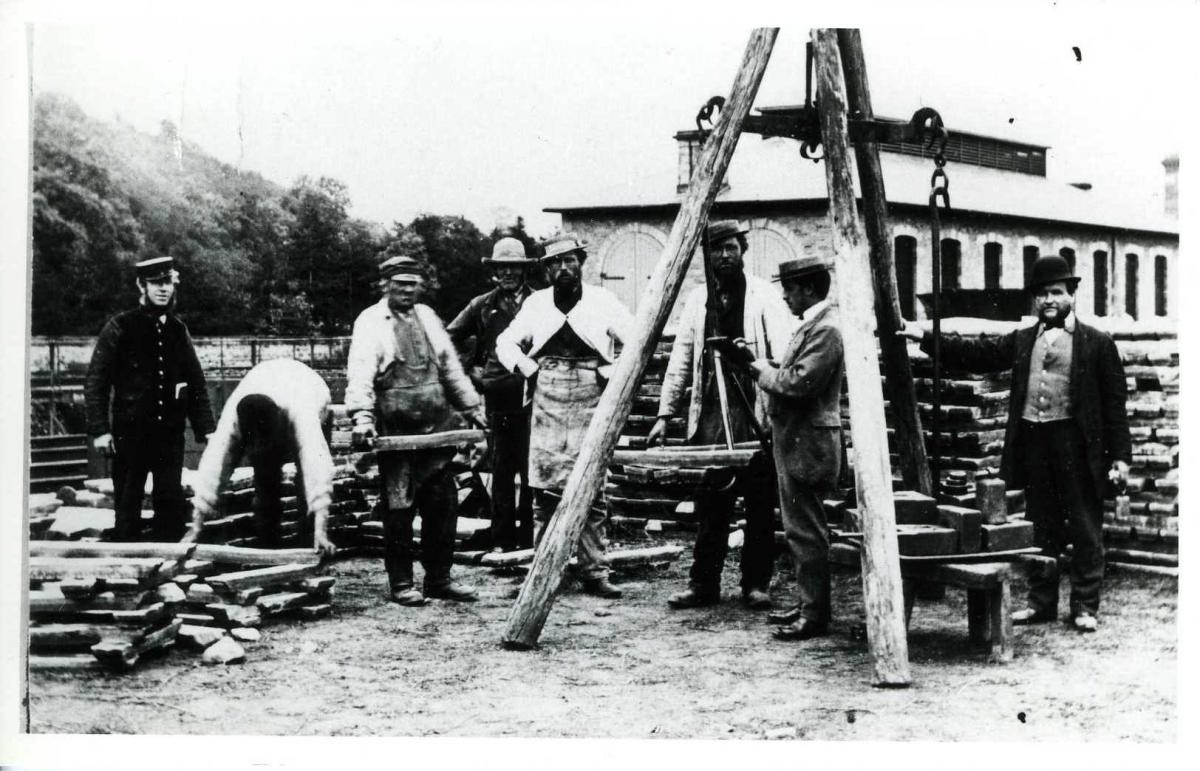

Grassington Players up and coming production 'Getting the lead' is about the area's former lead mining industry, here, the Players' Andrew Jackson tells us a bit about what life was like for the mining families.

LEAD has been mined in Upper Wharfedale, probably since Roman times and across the dale the traces of mining activity still scar the landscape.

But the miners themselves are ghosts from past ages whose lives have been reconstructed from handed-down memories, and insights from written records.

Grassington Players’ autumn production, “Getting the Lead” portrays the lives of the miners of Grassington and their families.

It takes us through a single year -1862 - a time when the lead was becoming scarce and harder to mine as the “boom and bust” years were over.

Cheaper imports were closing down markets and life was fraught with hardship.

Imagine living the life a miner.

You would be fairly young: at that time half the population was under 21.

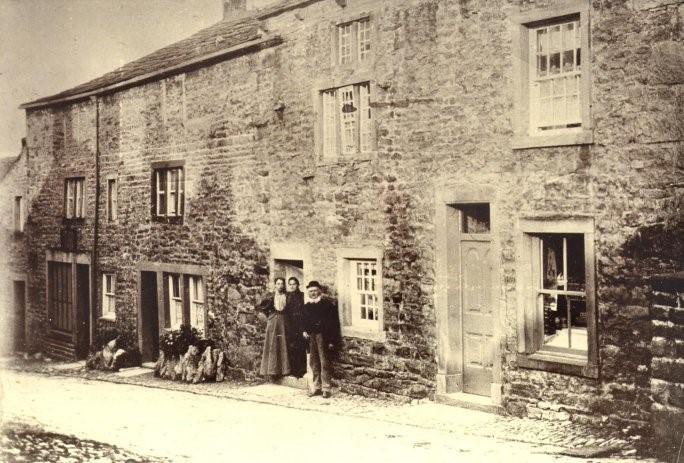

The average age at death was 47, and for smelters, ten years less than that. You would get up early in the morning, usually in the dark, and dress yourself in a dirty flannel shirt, a woollen waistcoat and trousers and a felted wool jacket.

Knitted leggings called “loughrams” would be worn in a vain attempt to keep the water out, and a felt hat was a poor excuse for a safety helmet. Heavy reinforced leather clogs complete your outfit.

You would walk the long uphill track from Grassington to Yarnbury moor and pick up your tools.

These would be weighed every three months to see how much they had been worn down, with the amount deducted from your wages together with charges for the tallow candles and gunpowder you had used.

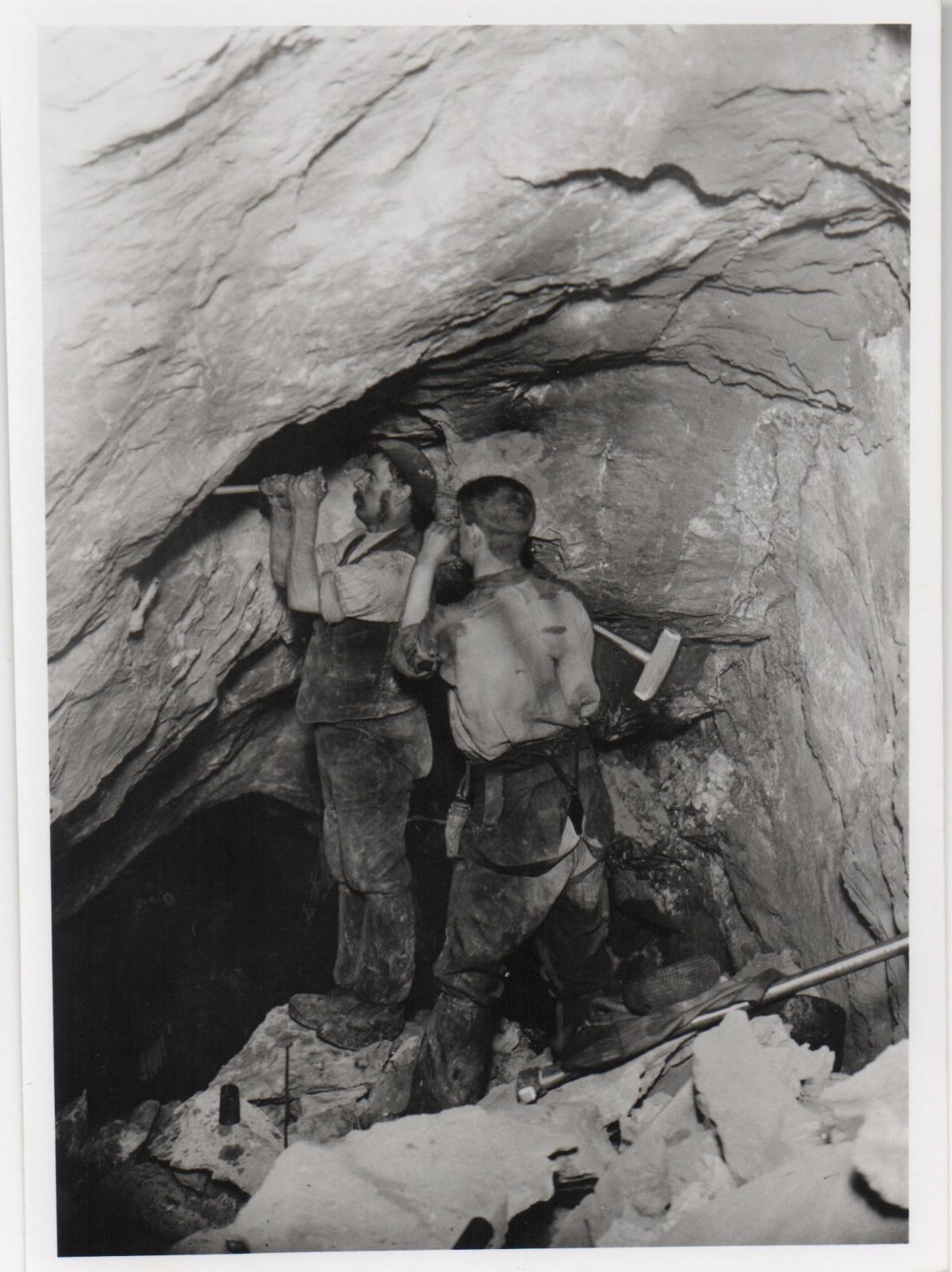

Then a walk across the moor to the shaft or level you were working in. Even then, you might have to walk up to a mile and a half in the complete darkness of the shaft before you reached the face.

The miners often worked in pairs, just by the light of a candle, one with a steel spike, and the other with a heavy hammer to drive it into the rock.

The hole would then be filled with gunpowder and the rock blasted down. There would be a choking cloud of stone dust, which over the years clogged up the lungs, and caused death from chronic lung disease.

As a precaution, miners were advised to grow a long moustache to filter out the dust. This, of course, was totally ineffective.

At the end of an eight hour shift, it was time to make the long walk home again, and back to a potato stew, or, if you were lucky to keep a pig or two, a bit of bacon. You would discuss the day by the light of a candle or an oil lamp, then perhaps to sit by the fire, reading if you could, or else head to the recently built Devonshire Institute (our ‘Town Hall’) to read or play cards. Some would be off to brass band practice, many to the pubs we still frequent today.

The miners worked incredibly hard and played the same way. Their way of life was one big gamble that you would strike a rich vein of ore and this formed their character. Much given to wagers and practical jokes, they would enjoy a fight, too, to the extent that the Police Gazette notes that Grassington was the first place in Yorkshire to arm the police.

But they loved to sing, too, and in the summer months would walk down from the mines and gather to sing in the square. They formed a choir, and even hauled a piano up to Yarnbury to sing between shifts. Brass bands were a matter of village pride and local village feasts featured hotly contested competitions between the neighbouring bands.

These musicians would also play at chapel services. The miners by and large eschewed the Church of England at St Michael’s, as there was a mutual loathing between the upper-class rectors and the rough miners. Instead, they turned to the Methodist and Congregational chapels, who preached that they mattered, and were concerned for their plight. There was considerable ill-feeling though when local bands were replaced by church organs and harmoniums.

Their wives did not have it at all easy, either. This work was just as dirty and dangerous as the mining. Many women worked the mines, not underground, but hauling buckets, washing ore, or turning windlasses, in addition to their household duties. The housework was backbreaking and never-ending. If you weren’t married, you’d work in the wool mills by the river.

In 1862, the writing was on the wall for the community. Conditions were becoming intolerable, and wages were falling. Families were beginning to drift away, knowing the lead was running out. The village heart was failing and 1862 was the last year that the Grassington Fair was held. 20 years later, the mines closed forever.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here