SKIPTON prisoner 18-year-old naval cadet Hans Sujata could perhaps imagine himself to be the unluckiest officer in the German Imperial Navy, writes historian Alan Roberts.

Fresh out of naval college he had only been on board German destroyer S-20 for three days and had apparently never been to sea before.

Just two hours into his very first voyage his vessel was attacked by a larger group of Royal Navy destroyers. Only 10 rounds had been fired before Sujata’s ship was sunk. Seven survivors were picked up by HMS Satyr and sent to London for interrogation.

Sujata could now consider himself to have been extremely lucky. Of a total crew of 74 as many as 49 German seamen had lost their lives. British Naval Intelligence kindly provided writing materials and duly forwarded Sujata’s letter to his family.

They did however include extracts from his letter in a secret dossier for circulation throughout the navy. From this we learn that Sujata was being well treated and that he had asked for some underclothing, something to smoke and some money!

Submarine commander Claus Lafrenz had always wanted to join the Navy. His father was against the idea and with the help of a large cheque persuaded his son to travel round Europe to see if he would change his mind. Accordingly Lafrenz visited Spain, France and spent five months in Edinburgh. He did not change his mind and eventually finished second in a class of 200 at naval college. He was considered to be a highly successful U-boat commander, and was able to provide the very first photograph of a cleverly disguised but armed British merchant ship known as a Q-ship. The German kaiser, Kaiser Wilhelm II (aka Kaiser Bill), was said to have been very pleased with the photograph.

British Naval Intelligence maintained that Lafrenz had been overconfident and had taken an unnecessary risk. In a letter written during his interrogation at Cromwell Gardens opposite the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Lafrenz said that the torpedo fired from British submarine C 15 had simply been a lucky shot and could not accept that he was at fault. Lucky or not, only 5 crewmen survived from the U-boat. Lafrenz himself was blown high into the air by the force of the exploding torpedo and suffered severe bruising to his chest when he hit the water.

The German officers and men at Skipton Camp were disconsolate when they learnt of the ceasefire in November 1918 which marked the end of the fighting. Germany had lost a war which a few months earlier they had fully expected to win. Some looked to religion for comfort, solace and some words of explanation. It fell to young theologians like Helmuth Schreiner to cater for their needs. Over 60 letters he wrote from Skipton Camp are contained in a huge archive in a German university in Münster together with the texts of at least ten sermons and his train ticket home.

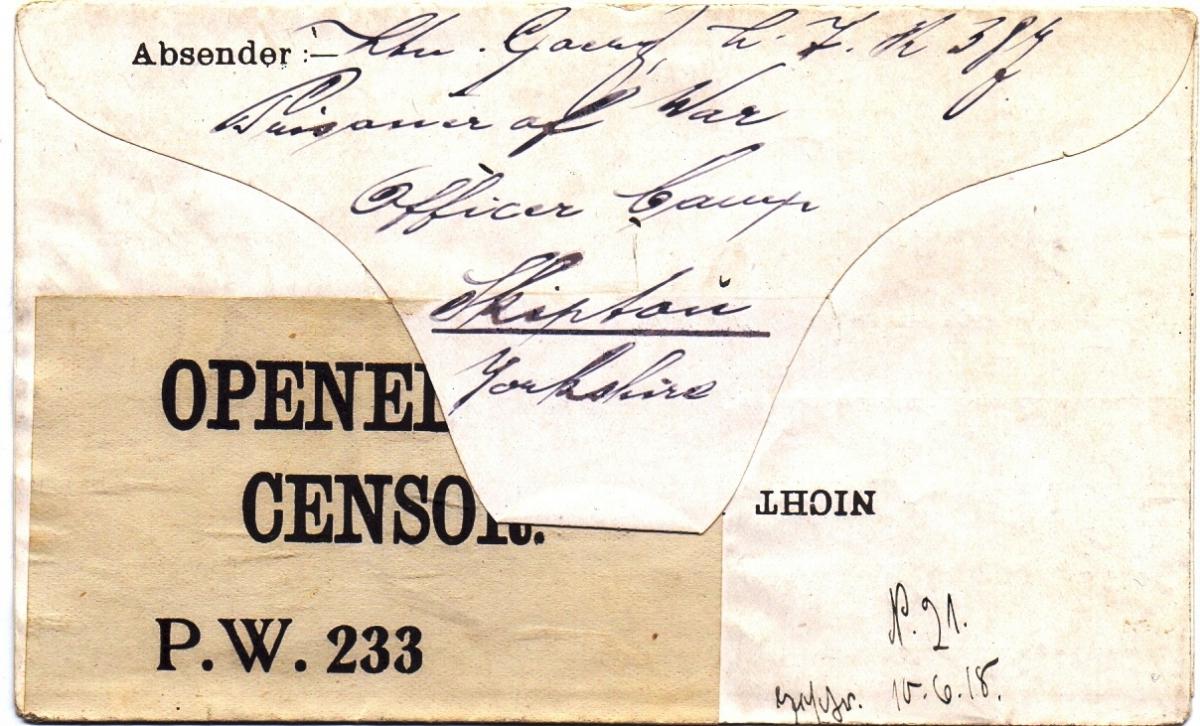

A few years ago a letter from Second Lieutenant Otto Goerg to his parents in Germany was found. The contents failed to live up to the excitement of the discovery. Goerg listed the parcels and letters he had received. He was sad that his grandfather was not very well, but pleased his mother had survived the winter. His family already knew about the death of Lieutenant Wommer, a young officer who lived just 8 miles away and was in Goerg’s regiment.

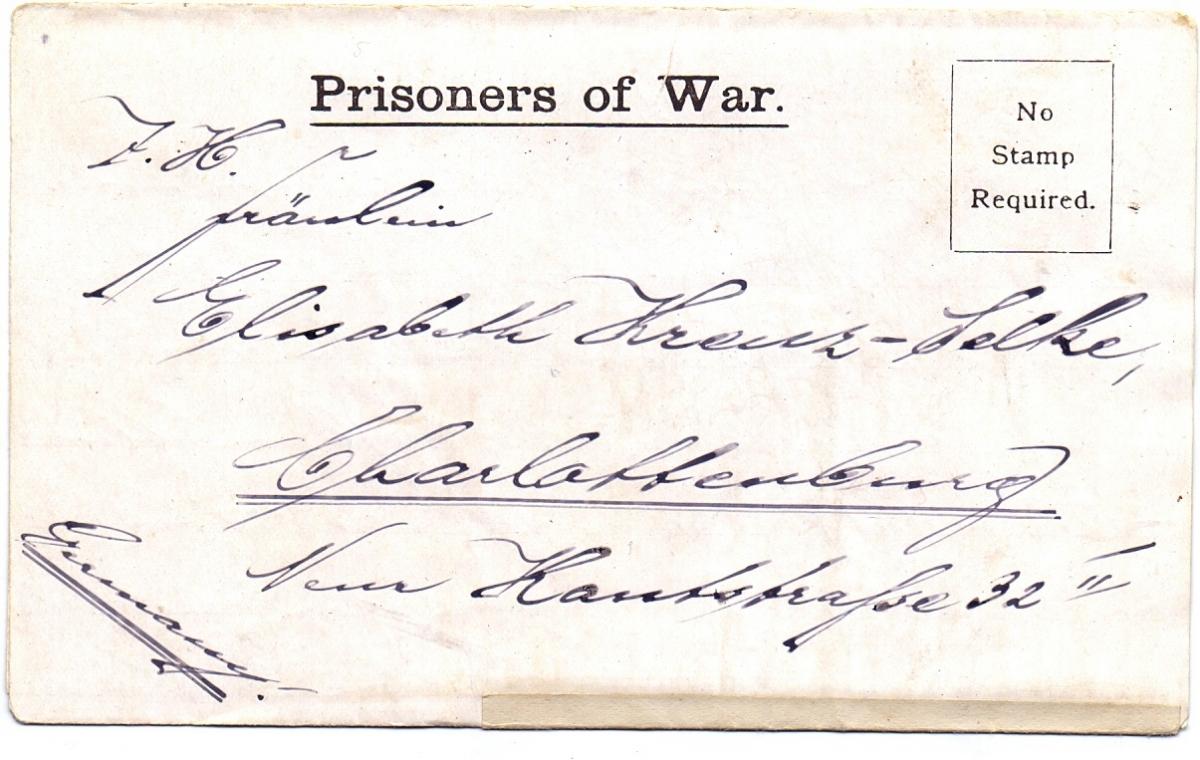

Goerg’s letters to his sweetheart reveal another side to his personality. Lizzie Krenz-Selke who lived in the affluent Berlin district of Charlottenburg was just 18 years old when Goerg was captured in the massive British tank offensive at Cambrai. In the first of two recently discovered letters Goerg tells Lizzie how much he yearns for her and sends her ‘hot, sweet kisses’. Two months later all that was to change. Goerg was clearly upset: he had had to wait three weeks for a letter from Lizzie and it contained just 31 words. His pen shook as he wrote the cold opening words ‘I can confirm that I have gratefully received your letter… written on 27th July.’ The course of true love did seem to run smoothly for two years later Goerg and Lizzie were married in Berlin.

Letter writing was not confined to the German prisoners. The British commandant Colonel R.W.H. Ronaldson was a war hero. His exploits in December 1914 had been duly recorded in Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s account of the campaign in Flanders. Two months later Ronaldson had been shot through the knee cap. The exit wound in the bone was the size of an old silver sixpence. Writing from Skipton a month after the end of the war, Ronaldson made a request to receive a ‘wound pension’ as he felt his appointment as commandant was likely to end at any time.

Sadly this was not to be for another year, and fate had one more nasty trick to play. In March 1919 Rudolf Kober, another young German officer, wrote to his parents at the height of the Spanish flu pandemic.

‘We are experiencing a simply horrific period. Nine died the day before yesterday, it was five yesterday, today it has been two officers and as I am writing the news has just come in that a further four of our comrades have fallen victim to the epidemic. So far twenty-six officers and nine orderlies have passed away. Is that not terrible and so far away from home too? The suitcases and trunks of the deceased are piling up. Just now another two have died, among them was a dear comrade from our own barracks. Then there was the third death from Hut 19… The ambulances are in continual use. For most of the prisoners it was their last journey. Most died at the hospital in Keighley and that’s where they are all buried.’

Amongst the 47 who eventually died was Goerg’s friend Lieutenant Wommer. Kober’s parents dutifully passed the letter on to the German authorities who unsurprisingly requested a full investigation. The report conducted by a medical officer appointed by the Swiss Legation in London had nothing but praise for the treatment the German prisoners received at the hands of the British doctors and medical orderlies. Today the ‘Skipton’ file is contained in a German archive located in the grounds of a building which was once the headquarters of Adolf Hitler’s bodyguard.

The two letters written by Otto Goerg to Lizzie Krenz-Selke can be seen at Craven Museum together with a full translation when it reopens later this year.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here