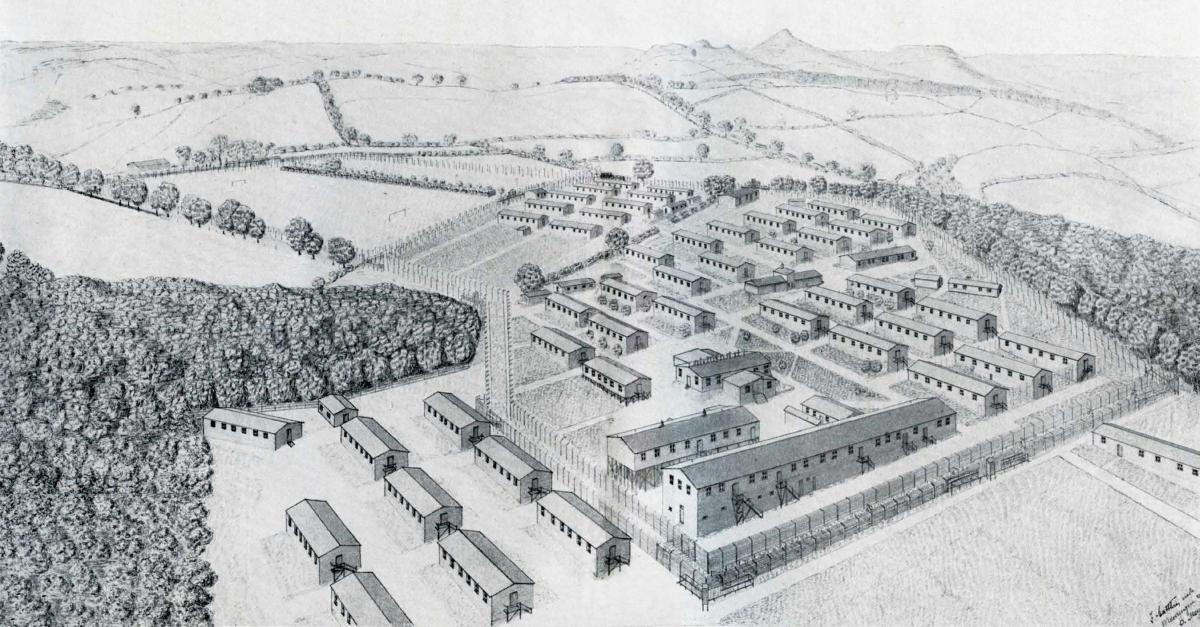

THE German prisoners in Skipton set up a theatre in the camp in September 1918, details of which have been translated from diary notes, smuggled from the camp when the prisoners were repatriated.

Anne Buckley, a lecturer in German at the University of Leeds, has been leading a team who have translated the diary into English. The book is being published by Pen and Sword and will be available in February.

Meanwhile, extracts about life in the camp have been aired with readers.

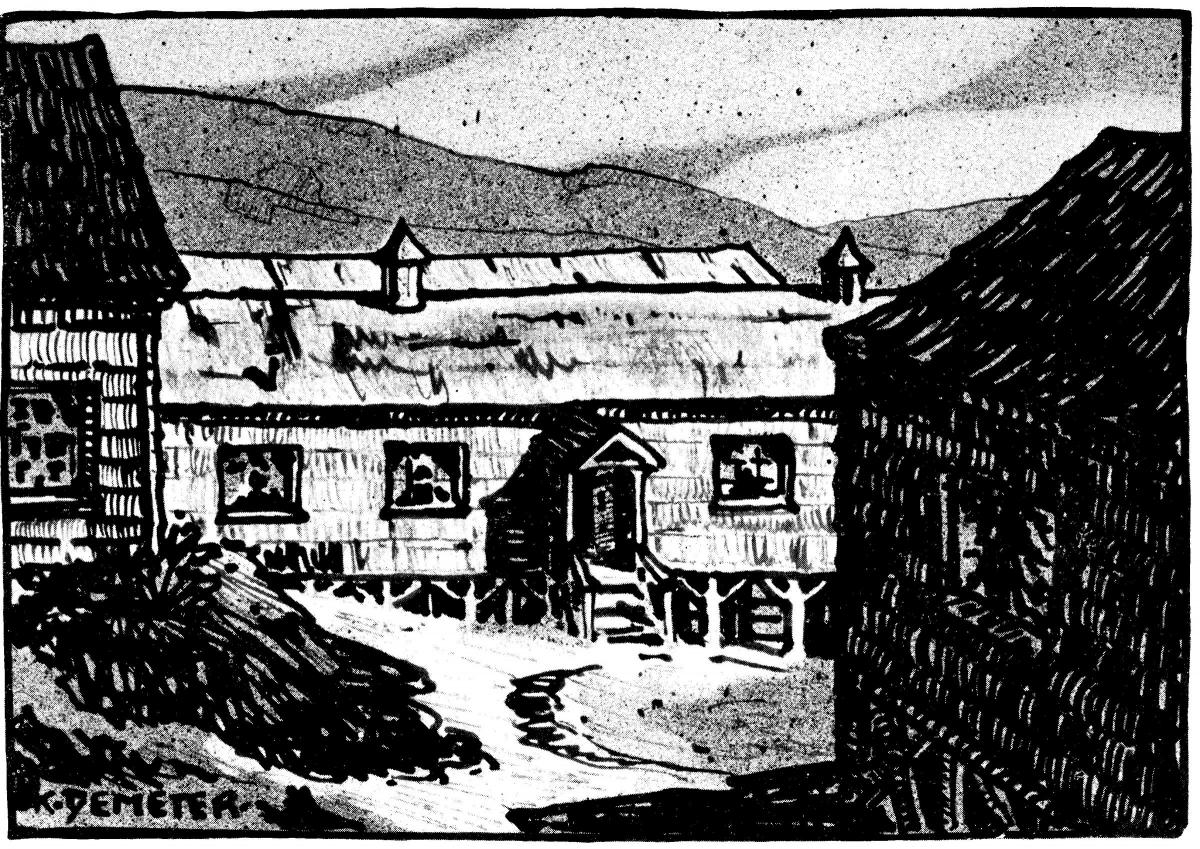

Here, a translation of PoW Friedrich Siems’ entry tells us of the theatre the men used.

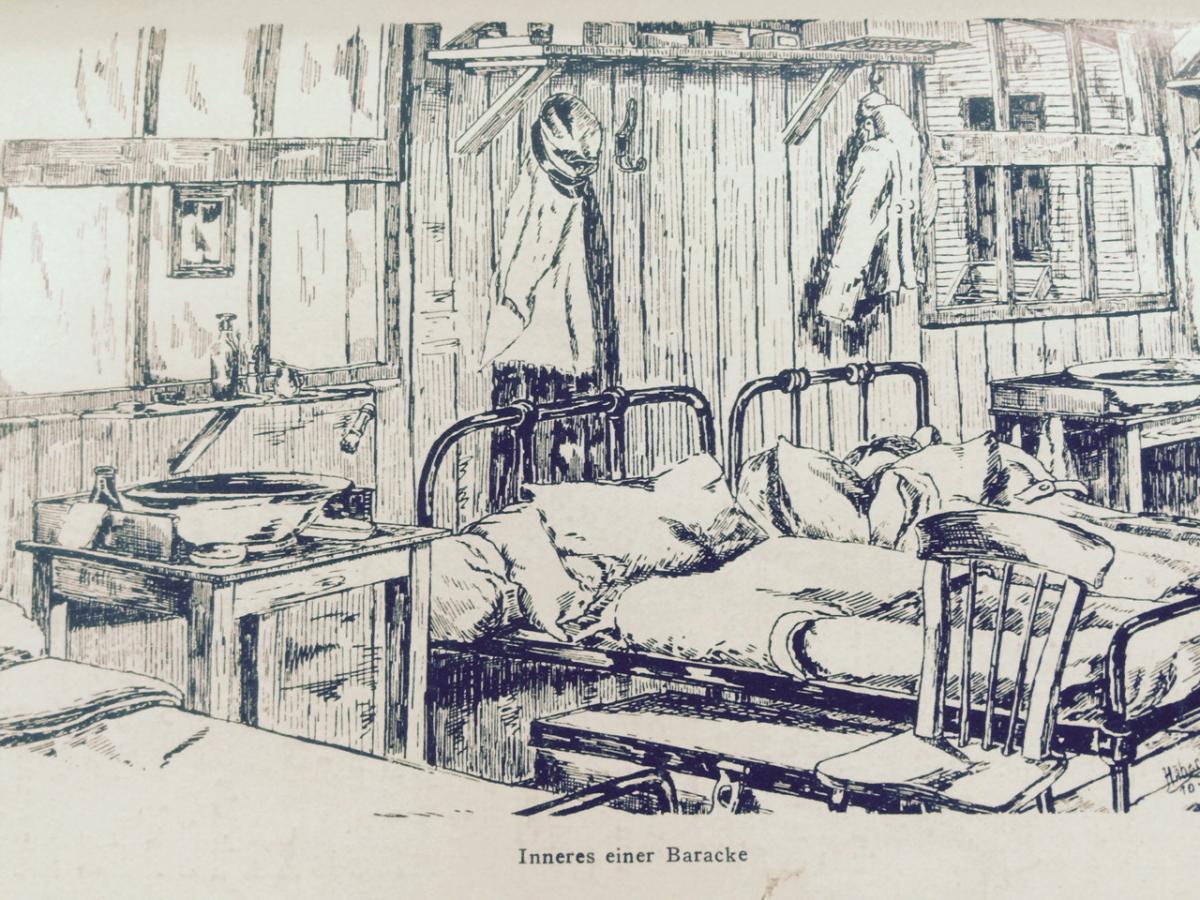

Skipton was an officers camp, an agreement of the Hague Convention meant the prisoners did not have to work so theatre was one of a number activities they organised to occupy themselves and to try to create a purpose in their lives.

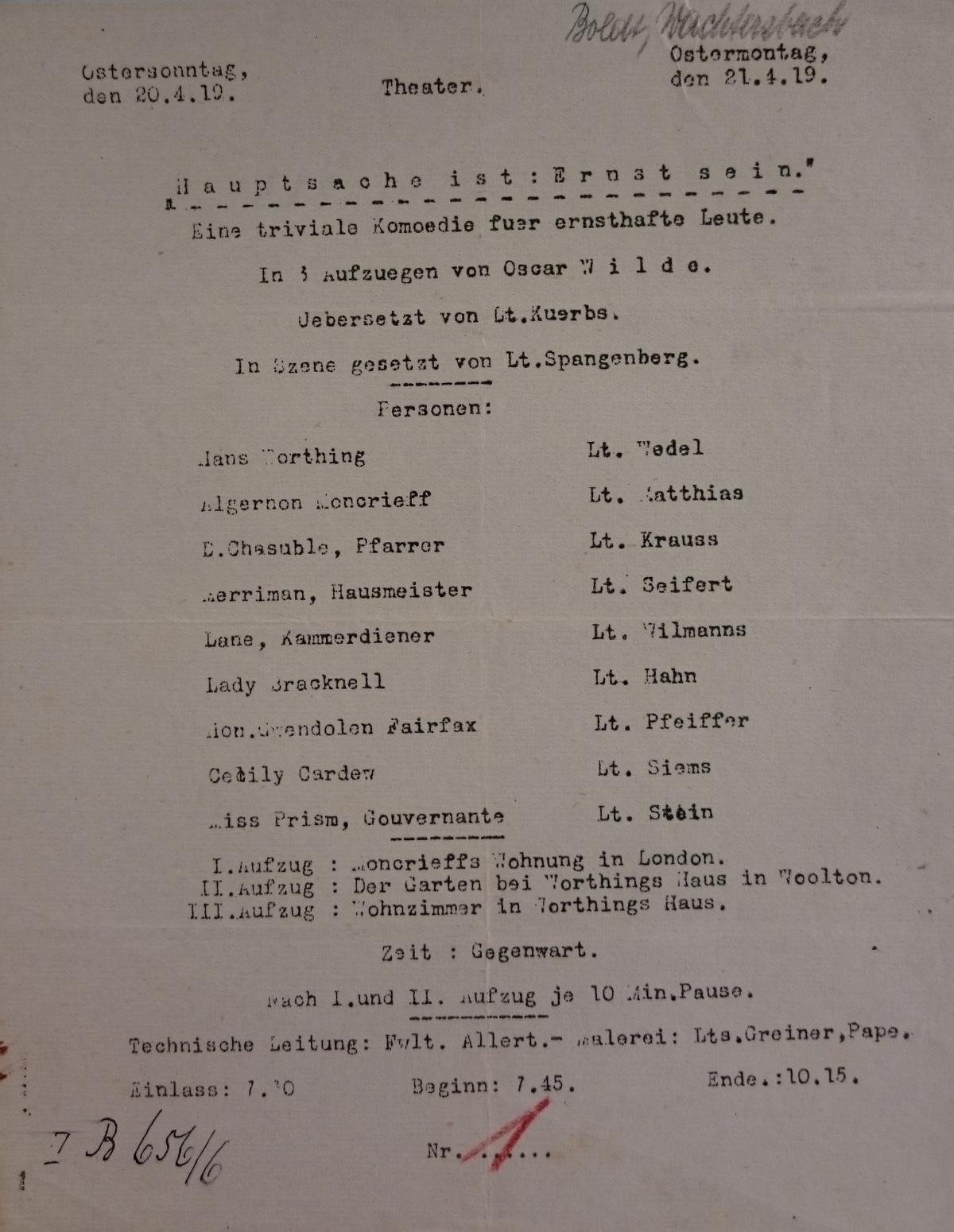

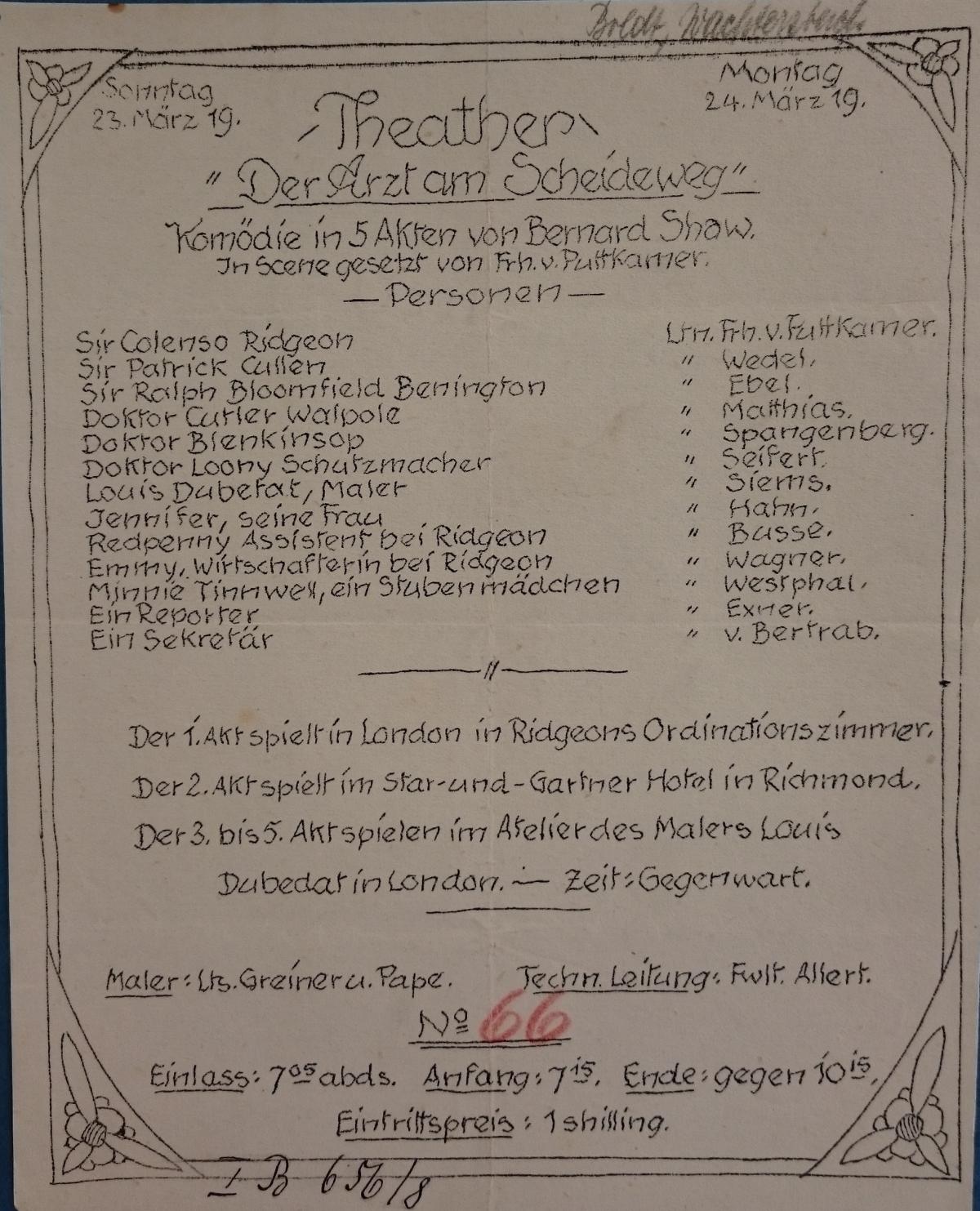

The prisoners performed at least 23 different plays in the camp theatre before their repatriation in October 1919.

Siems went on to become a well-known theatre actor and director in Germany after the war. Contact has recently been made with his family by Anne Buckley and student Harriet Purbrick.

“In September our new director of entertainment accomplished his first and most significant feat: the creation of this camp theatre.

He gathered together a number of comrades who were willing to be actively involved as performers or technical assistants. The number of members soon increased and by October a permanent organisation was established, separated into performance and technical departments.

The inner circle within the theatre committee consisted of the scriptwriter, the director, the treasurer, the head of the technical department and three actors selected from among the members.

The monthly general meetings were not just to discuss business; they also offered cheerful and often frivolous entertainment such as poetry and light verse, and popular songs, in a relaxed environment with coffee and cake, cocoa and cider.

It is not only warfare that involves money, money and more money, but the establishment and maintenance of a theatre is also impossible without this widely sought-after commodity.

The Skipton camp community recognised this, and so provided the theatre group with about £50 from canteen funds. This was all spent on building the stage, creating suitably elegant surroundings and purchasing the first basic props and costumes. After that the theatre was completely reliant on income from performances.

The small offices and the library at either side of the stage served the actors as make-up and dressing rooms.

It was unbearably overcrowded there on the days of a performance, particularly for plays with a long list of characters. But good humour and love for the cause made the most makeshift situation bearable.

A large number of bright gas lamps beamed a dazzling light over the stage. The lamp nearest the stage was transformed by a reflector into a kind of spotlight, in front of which different coloured pieces of glass could be positioned using a mechanism backstage, thus immersing the stage in red, yellow or blue light.

Some, but not all, of the costumes also originated in the camp. Most of them were purchased either through the store manager or directly from London from the company C.H. Fox, who also provided the wigs and makeup. It proved very useful that our comrades from the Navy kindly put their uniforms at our disposal for plays that required formal costumes. The uniform buttons and badges were covered with dark fabric to make them into immaculate civilian clothes. Over time, the theatre acquired a collection of costumes that included almost all types of formal suits and a number of pieces of fine women’s clothing with all the accessories. These were carefully stored in sturdy crates on the other side of the barbed wire under the watchful eye of the English, and were only brought into the camp for the performances.

The highest demand for props and costumes was for the Christmas performance of Turandot. One of the camp artists designed the costumes according to the director’s instructions, the head of the technical department cut them from colourful, cleverly dyed fabrics, and then a number of group members sat for weeks sewing, stitching and adding trimmings. Twenty complete costumes had to be finished within three weeks, and while one room served as a tailor’s workshop, in another fantastical headdresses, wide oriental swords, pointed and twisted daggers and other weapons and equipment were created by the skilled hands of the comrades in the technical department.

From the outset, the theatre management was aware that performances should first and foremost provide amusement and liberating laughter. Nevertheless, we attempted to put on comedies of literary value and interest as well as cheap farce. Finally, for the sake of genuine intellectual stimulation, it was also the aim of the theatre management to make room for modern drama with its profound awareness of social problems. Therefore a ‘studio theatre’ was established, which evoked keen interest and lively approval in March with Strindberg’s Creditors and, after a preliminary and explanatory lecture, with Ibsen’s Ghosts in May. This is how the Skipton theatre, with considerable effort, sought for many months to serve fellow imprisoned comrades. When, one day, we are free to return to our life’s purpose, using our strength in the service of the Fatherland, then may the thought of the theatre be one of the shining lights among the many sad recollections, displacing the grey memories of the camp with a conciliatory glow.”

Next week will feature Siems’ life and work.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here