AT the entrance to Ingleborough Estate Nature Trail in Clapham, there stands a magnificent American Redwood tree.

Despite its size, it’s only a youngster, a mere 150 years old, but it is something of an oddity in the Yorkshire Dales, and likely a legacy of one of the former Farrer custodians of the estate, who brought back a variety of plants from his travels abroad.

It was the first of many fascinating things I learned during a day spent trying hard to understand ‘ 450 million years of geology with Ingleborough Cave’, and it had nothing to do with rocks.

Our guide, John Cordingley, a former biology teacher, is a cave diver, and fell runner, who was officer of the British Cave Rescue Council for 27 years. Now, he takes people on fascinating tours of the area, with Ingleborough Cave the icing on the cake.

I went along with a bundle of questions: how old are limestone pavements, are they older, or younger than dinosaurs, and why do they look volcanic; why is there beach sand so high up and nowhere near the sea, and erratics, how, just how...

It is safe to say my knowledge of geology and geography is somewhere between primary school and GCSE level. It was handy that joining us on the day were two geography teachers, both of who were planning school trips to the cave. So, as well as John, they chipped in, helping to answer some of my questions and to patiently help me grasp the concept of so many millions of years and how the area around Ingleborough has become what we see today.

John was an amazingly enthusiastic guide, and never tired in answering questions, he really must have been an excellent teacher, so endlessly enthusiastic he was about his subject.

It took us well over an hour to walk the mile or so to the entrance to Ingleborough Cave along the trail, as we learned how the lake was in fact artificial, how one of the Farrers planted alpines by shooting them out of a gun into limestone across the lake; and we stood on the Craven fault - the presence of which means fracking will not be allowed in Craven.

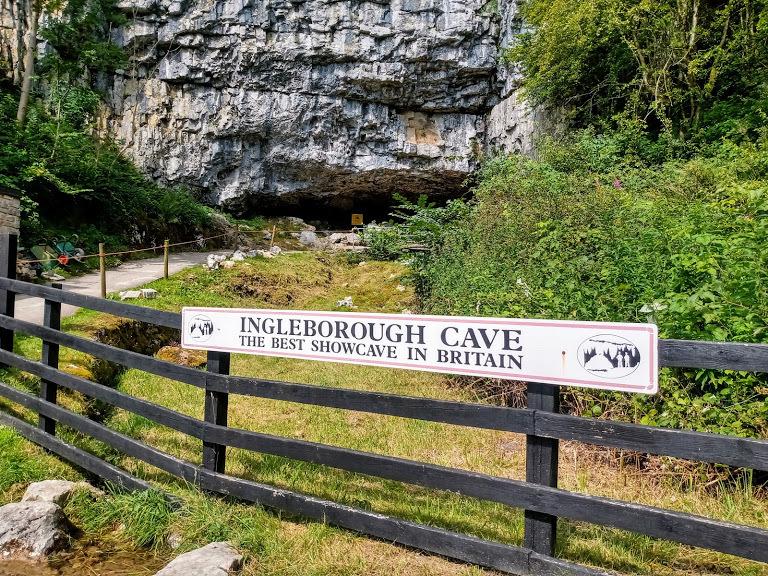

With coronavirus restrictions in place, there are few guided tours taking place inside the cave; people go inside with face masks, and can investigate on their own. John told us how the cave was first opened up in Victorian times, when James Farrer in 1837 broke through some rock, and opened up the secrets lying behind.

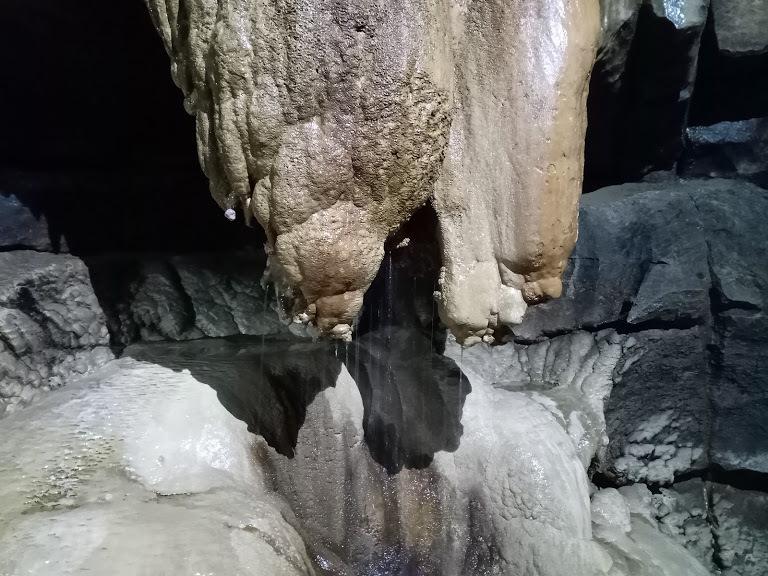

It threw up the question, would modern day cavers do the same thing today, or leave things as they were, perhaps trying a different way to get underground. It was interesting to see later on another passage blocked at the end by a stalagmite and John describing how instead of knocking it through, he and his colleagues had been busy for the last several years inching their way along another passage, of about two feet deep, in the hope it might get them to the other side.

Stalagmites (up from the ground) and stalactites (coming down) are scattered all over the cave, some had been vandalised in Victorian times, with bits chopped off, presumably to make interesting ornaments. There are also eerie lakes, and amazingly, fossils of sea creatures in the rock.

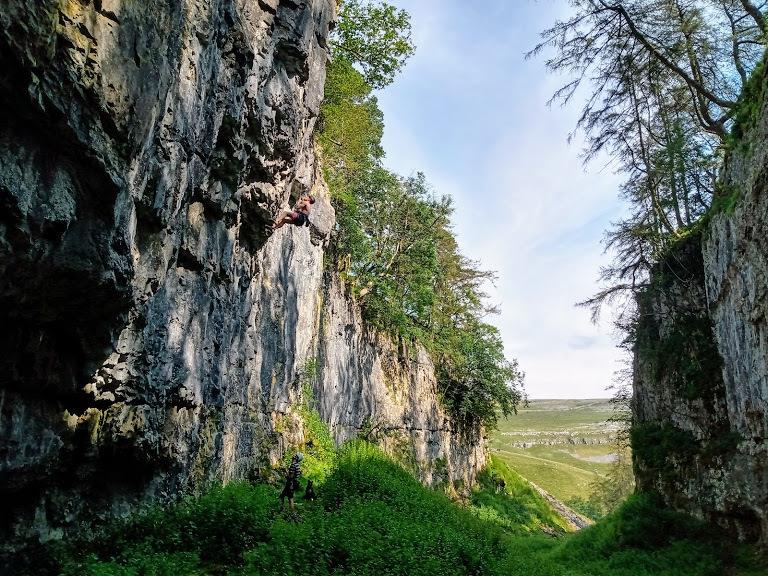

Back out into the sunlight, after the cold of the cave, it really is cold, do take along a jacket, we proceeded along the well trodden path to Ingleborough, via Trow Gill gorge, where John told us a story about a film crew and an alligator. From there we proceeded to Gaping Gill, where the yearly open event had to be cancelled this year because of the coronavirus.

One of my fellow students on the tour, said: “Learning about the millions of years it took to make our unique Dales landscape was quite mind blowing. The amount of time involved to make limestone hills out of crushed sea creatures is almost impossible to grasp.”

To find out more about geology tours, visit: ingleboroughcave.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel