READERS may have noticed that Scale House , Rylstone, is currently on the market. For the German POWs in Skipton, Scale House was the most popular destination for walks from the camp. They knew the property as the ‘Green Palace’ as it was covered in ivy a century ago.

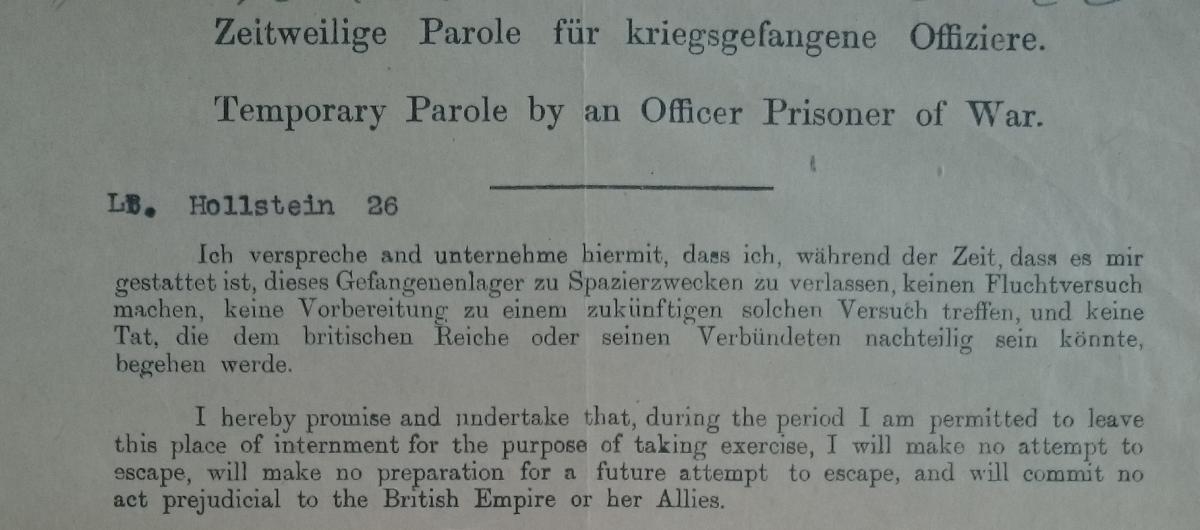

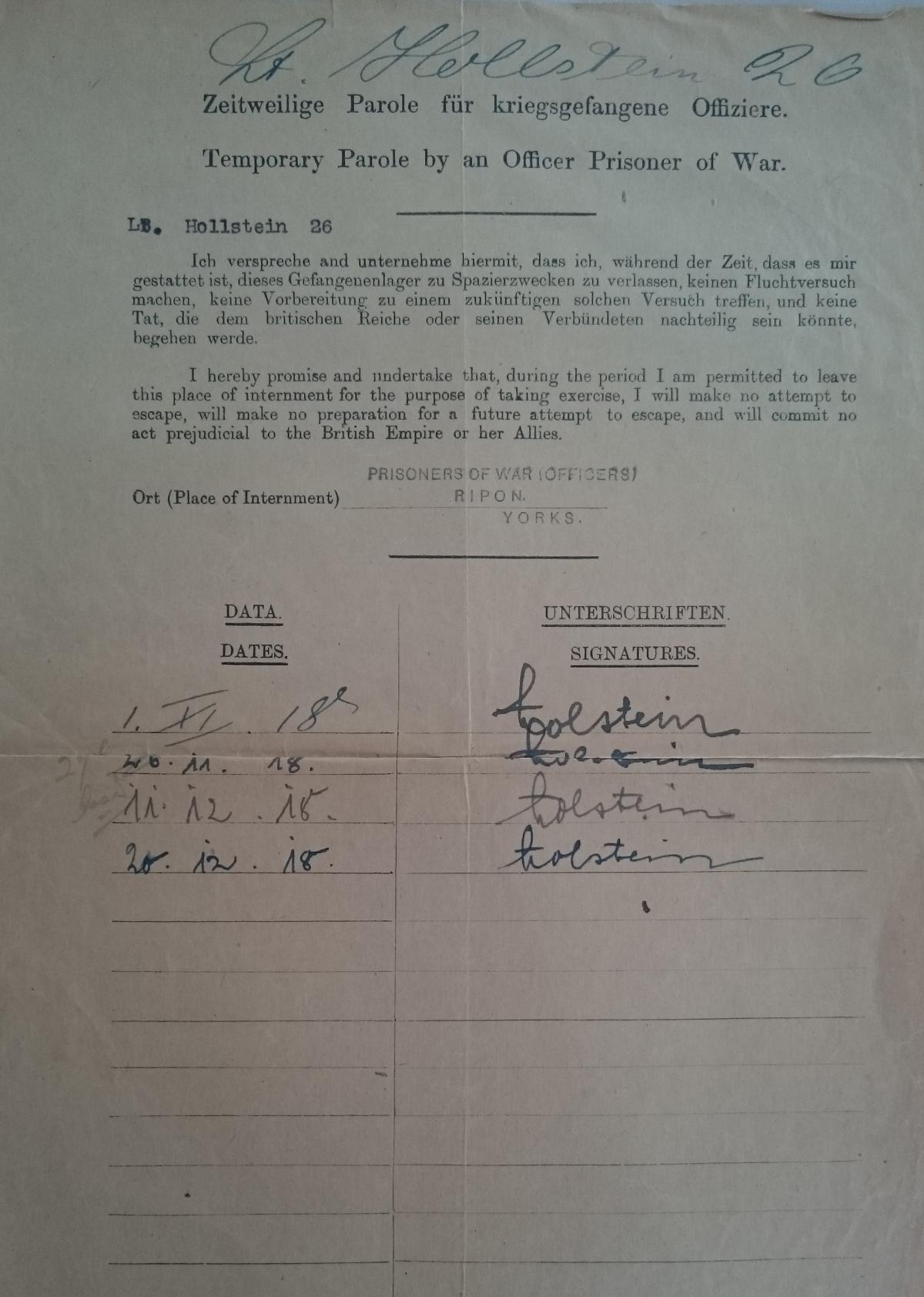

A reciprocal agreement between the British and the Germans meant that officer POWs were allowed out of the camp for walks accompanied by a British guard if they signed a parole form promising not to escape.

In the following extract from the translation of the book ‘Kriegsgefangen in Skipton’ written by the German POWs, prisoner Ernst Schrader describes the prisoners’ walks:

“In addition to the comfort provided by the activities in the camp and by one’s own thoughts, the walks also offered a pleasant distraction.

From the autumn of 1918 one of our staff officers put a great deal of effort into planning these very proficiently, having procured a large map of Skipton’s surroundings.

We walked daily for up to two and a half hours and got to know some of the surrounding villages: Carleton, Cononley, Draughton, Rylstone, Gargrave, Broughton (with the beautifully situated Broughton Hall) and Halton East among others.

On some days we ventured up onto the nearby ridge of hills through woodland, moorland and gorges. We saw the ruins of Norton Tower and the place where a tower belonging to the Cliffords had once stood. We could rarely enjoy the view because the area was almost always shrouded in mist and fog.

These walks were of great benefit for the physical and psychological wellbeing of all comrades, some of whom never missed a walk.

For a few hours it gave us the sense of freedom. The varied beauty of this charming region delighted our eyes; the refreshing movement improved our posture. The frequent change of route meant we could get to know the countryside, the people, and foreign customs and make comparisons with the Fatherland.

The first walk outside the camp was particularly impressive in military terms because the accompanying officer had retrieved a huge sword from the armoury of his forefathers in order to defend us to the death.

The sword’s basket hilt was so large that it could not be worn at the side. It was therefore fastened to the hero’s left breast.

Nevertheless, the tip almost reached the ground while the hilt protruded over his shoulder – a truly prodigious, awe-inspiring and terrifying murder weapon.

Unfortunately, the bearer was a dignified elderly man, somewhat bowed down by the maturity of his years or perhaps even by the weight of his weapon.

He brought the sword with him only once, probably because it became clear that the area surrounding Skipton was, after all, not as dangerous as had at first been assumed.

Once we are all assembled outside the gate, they count us as a safety measure and then we set off. We are always preceded by an English officer, who has kindly been given to us as a guide through this entirely unfamiliar landscape.

That is, however, not enough. At the rear follows another English soldier, who, to our astonishment, is armed with just a bayonet.

After all, we are used to seeing the other Tommies ordered to protect us always carrying a rifle and mounted bayonet. I can only hope that he at least has a hidden revolver with him as well.

Under this military escort, we then slowly leave the camp’s immediate surroundings. Of course, the rate of motion varies greatly between 40 or more comrades of various ages, various temperaments and various ranks.

The consequence of this is that the line soon becomes noticeably strung out. Naturally, this then puts us at risk. Just imagine a sudden attack from the side and think about the inadequate cover! That could be disastrous.

The warrior at the rear is therefore wisely ordered, as a precaution, to give a shrill whistle whenever the distance between himself and the guide seems to him to be too great.

He does so reliably and frequently. The walkers at the front stop until the line is once more of the right length, or rather the right shortness, then they set off again.

This extremely amusing game is repeated very frequently to begin with, until we have mastered the correct average pace and, above all, until we have given our kind hosts the idea of establishing two walking groups – the so-called fast walkers and the normal walkers.

Naturally, I do not wish to imply that the fast walkers themselves were abnormal; it was only their pace that was not always normal. Besides, nothing seems abnormal to us prisoners anymore.

In our home country we are used to walking along the side of the road on a raised pavement, while here we have been shown the benefits of walking on the road itself.

The pavement is surfaced with hard flagstones or made from coarse gravel that wears down the soles of our shoes unpleasantly. The road, however, stretches before us with a perfectly smooth, soft, springy surface. In England even the rural roads are surfaced with tar.

At home it is common to take a walk to the nearest hostelry. We do the same here. Admittedly, I am only familiar with one of these convenient inns in the immediate vicinity of Skipton: The Craven Heifer.

This whole region is named after Lord Craven and the heifer was a particularly powerfully built young cow from the local area that then also won first prize at a show in London.

After all, London is world famous for the large cows within its city walls. So it was pleasing to hear that our Skipton did better than London. Above the entrance to the inn there is a magnificent painting that has unfortunately now suffered from the inclement climate but still decorates the outside of the establishment, a poor likeness of that magnificent animal.

We stand at the door of the inn considering whether or not we should fortify ourselves a little within, when we unfortunately remember the cursed slip of paper on which we promised not to jeopardise the English state in any way.

How could we then drink up their ‘hope ale’ and whisky! We are also well aware that we are very well fed by our kitchen ‘at home’, which saves us money. We therefore turn around and, after an absence of one and a half hours, reach the gate of our fortified camp once again.

How we long to get inside! Each man pushes to be the first. But before we enter, our military guard of honour must all gather together and the gate, so under threat, must be duly manned. Then the interpreter reads aloud the list of names and hands each man his declaration, gracious salutes are exchanged and finally we are once again happily at home behind the barbed wire.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here