In a remarkable piece of journalism a reporter from the other local newspaper, the West Yorkshire Pioneer, was allowed exclusive access to Skipton Camp after the German officers and men had left. The departure itself was extremely rapid, writes historian Alan Roberts

The Craven Herald reported that news of the ‘ejectment order’ was received on a Saturday while the prisoners themselves had departed on the following Monday morning.

Prisoners, captured in the uniforms they happened to be wearing, had in the meantime accumulated an array of personal possessions. The German officers gleefully reported that they had successfully smuggled out the manuscript of their memoir Kriegsgefangen in Skipton. Other officers had no difficultly taking their own personal papers home with them.

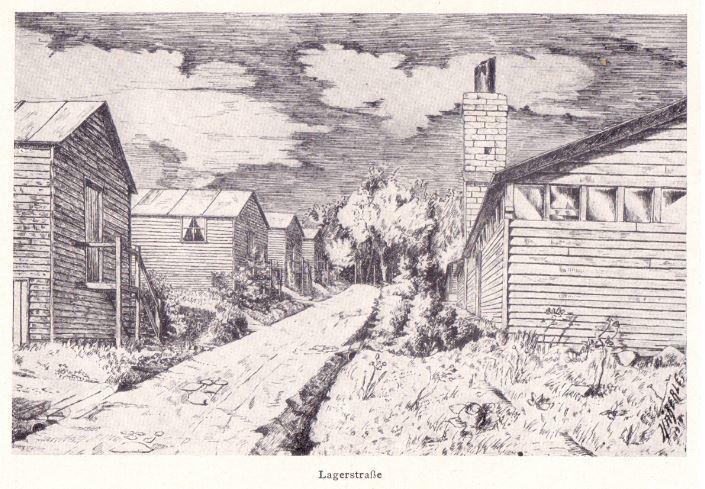

In fact the German officers had acquired more than they could carry. There was plenty for the reporter to examine as he explored the ghost town of a Raikeswood Camp that had been abandoned in the course of around forty-eight hours. Granted entry to the camp immediately after the Germans had left, the reporter surmised that the Germans must by then have been on their own side of the North Sea. A detachment of some 45 British soldiers was still being deployed to guard the camp.

In their memoir the German officers continually profess their loyalty to a kaiser who had been compelled to leave his home country the day before the ceasefire had been signed. Although one of the main topics of conversation was ‘How I was captured’, there was little mention of the war within the book itself. There is no criticism of the kaiser or his military leaders.

In a hut once occupied by naval officers, large maps of South America were hanging from the walls. Drawn in brightly coloured chalk and inks, they celebrated the victory of Admiral von Spee at Coronel in the Pacific Ocean in 1914, and no doubt mourned his ultimate defeat by the Royal Navy off the Falkland Islands in the Atlantic a month later. With plenty of time on their hands the German officers had ample opportunity to fight and refight the key battles of the war, and work out what went wrong.

One prisoner had taken refuge in mathematics. His attempts at problem solving lay abandoned on the floor amidst the haste of his departure. Another prisoner had been taking the trouble to learn the language of his captors. Someone else had begun a diary. The reporter felt that ‘diaries of captivity are unwholesome memorials. Their chapters are barren cheerless epitomes and the dust heap is the best place for them’. In truth there are quite a number of surviving diaries written by German prisoners during the First World War, but the German memoir from Skipton is believed to be unique. It is a compilation of the work of more than fifty prisoners, judiciously edited to provide a more consistent narrative. What is lost in spontaneity is gained in the breadth and depth of the work.

Elsewhere the barber’s shop was festooned with what the writer called ‘gay prints from gay periodicals’. These were in fact pictures of attractive women taken from the pages of the men’s magazines which the officers were able to have sent direct from Paris.

The reporter correctly assessed the mood swings which plagued a prisoner’s life ranging from ‘morbid dejection to unreasoning gaiety’.

The showers contained countless examples of abandoned clothing; a field-grey cap with its regimental badge obliterated, a pair of enormous boots, a cardigan and a pair of worsted trousers patched with red cloth. The nearby heating apparatus indicated the likely fate of the garments.

The reporter waxed lyrically about the modern cooking facilities available to the prisoners. The ovens, he said, were in first-class condition. The equipment was ‘remarkably efficient’ and many articles were of a ‘wide and eminently useful variety’. The German officers were serial complainers and failed to recognise the excellence of the facilities that had been provided for them.

The huts at the camp were being considered by for use as temporary housing. Despite the German officers’ protests about the inadequacy of their accommodation, the huts would sell for record prices when they were auctioned the following summer. The reporter worried that the huts had not been constructed in sections, and that the woodwork might suffer if they had to be dismantled and reassembled elsewhere.

The journalist had used his undoubted skills to paint a vivid picture of what he had seen as he walked around the camp. The Craven Herald no doubt echoed the sentiments of the people of Skipton when it said that the German officers and men should no longer ‘pollute the atmosphere here with their presence’. The German officers had joyfully departed to build their new fatherland. The Allied commander in chief Ferdinand Foch was gloomy. Commenting on the treaty recently signed in Versailles he said, ‘This is not peace. It is an armistice for twenty years’. Unfortunately he was quite correct Britain would again be at war with Germany, and his estimate was only a few months out.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here