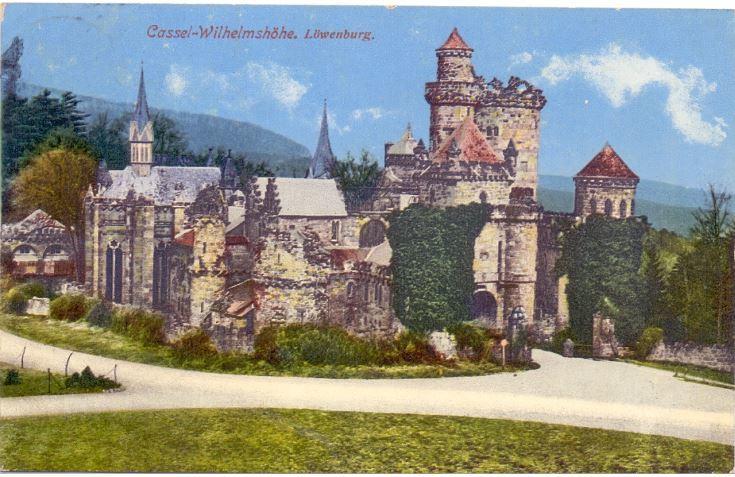

EDWARD Snee attended a grammar school in Kassel in the centre of today’s Germany. He would eventually spend a total of six years there. His knowledge of German was superb, particularly in the way young people in high schools and universities spoke. Many of the German officers at Skipton were not very much older. Snee seemed to understand the German way of thinking, and the officers perhaps tended to over-confide in him. Sadly for them Snee was first and foremost a British officer.

Before the war he had been a schoolteacher in Kent. His natural friendliness was doubtless part of his training, yet there would be limits to what was acceptable: anything he discovered that was in any way untoward would be reported to the appropriate authorities. The Germans also complained that he started many rumours in the camp which led to outbursts of great excitement followed by intense disappointment when they turned out to be false. The Germans saw this as a deliberate attempt on Snee’s part to ingratiate himself with them. The German officers wrote in detail about this and other experiences in their book ‘Kriegsgefangen in Skipton’. Unfortunately Snee who died many years ago can no longer give his own version of events.

The German officers correctly reported that Snee had spent time in South Africa. He spent three years teaching at Pietermaritzburg College where the school magazine reported that in September 1914 Dr Snee had arrived from England to take charge of one of the third forms. His experience as a teacher of modern languages, it said, had already proved of benefit to the school. Today Maritzburg College is an extremely prestigious school with fees of around £6,500 for boarders. It has been ranked as the fourth best high school in Africa by ‘Africa Today’. Famous old boys include South African rugby world cup winner Joel Stransky, novelist Alan ‘Cry the Beloved Country’ Paton, and England cricket captain Kevin Pietersen.

Snee was also an examiner in German at the University of the Cape of Good Hope. He had applied to join the South African Contingent, but was rejected due to poor eyesight.

The First World War lived up to its name with fighting involving almost every continent. South African forces were active in both Europe and Africa. The war in German East Africa (today’s Tanzania and parts of its neighbouring countries) would continue until after the Armistice was signed in November 1918. Skipton prisoner Baron Karl von Ledebur was a government official and captain in the German defence forces. He was captured when the hospital where he was recovering from a leg amputation was overrun by the British. He faced a long and arduous journey before he arrived in Skipton. He was repatriated before the end of the war as he was too badly wounded to take any further part in the conflict.

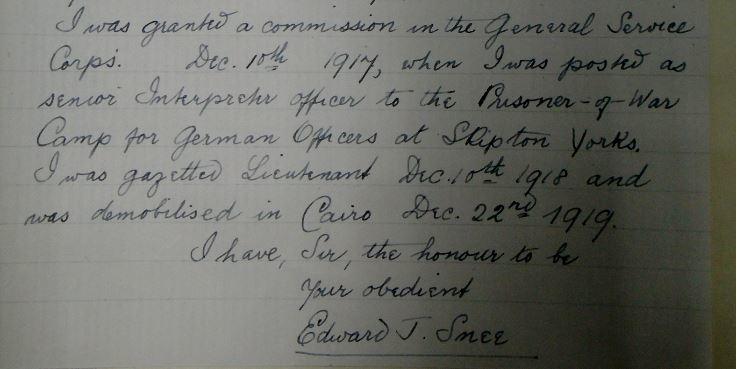

Returning to Britain in 1917, Edward Snee was keen to join the army. His strong point was his undoubted languages skills. Examined by no less an organisation than MI6 he unsurprisingly gained the highest possible grade in German, and his French was not too bad either. Snee’s original application for a commission survives. It sheds some interesting light on the requirements for an officer in the British Army.

Snee had studied at universities in Germany, Paris and London where he had obtained an MA in German. There was some mention of a PhD. from Heidelberg, and he had styled himself Dr Snee in Africa. He was anxious to make it known that he himself had been educated at a private school in London. As a young teacher he had also been an officer in the school cadet corps at Sittingbourne in Kent. He could not call himself a good rider, but said he had done a bit of riding in South Africa. This man was ticking all the boxes and determined to get his commission as an interpreter.

Two years later and Skipton Camp was due to close. Most of the British guards were demobilised in convenient places like Ripon. Not Edward Snee. He had sailed on the SS Czar and ended up being ‘demobbed’ in Cairo. He would work as an Egyptian government official before returning to teach modern languages in Bexhill in Sussex.

His childhood had been sad. His English mother had died when he was just four months old. His father became manager of Bass, the brewers, in Paris. At two years old Edward was a ‘boarder’ in the house of a naval pensioner. Ten years later he had been packed off to boarding school. Life cannot have been easy for young Edward. His undoubted talents were to remain underused as problems with his eyesight would prevent his excellent language skills from being used to greater advantage during the war.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here