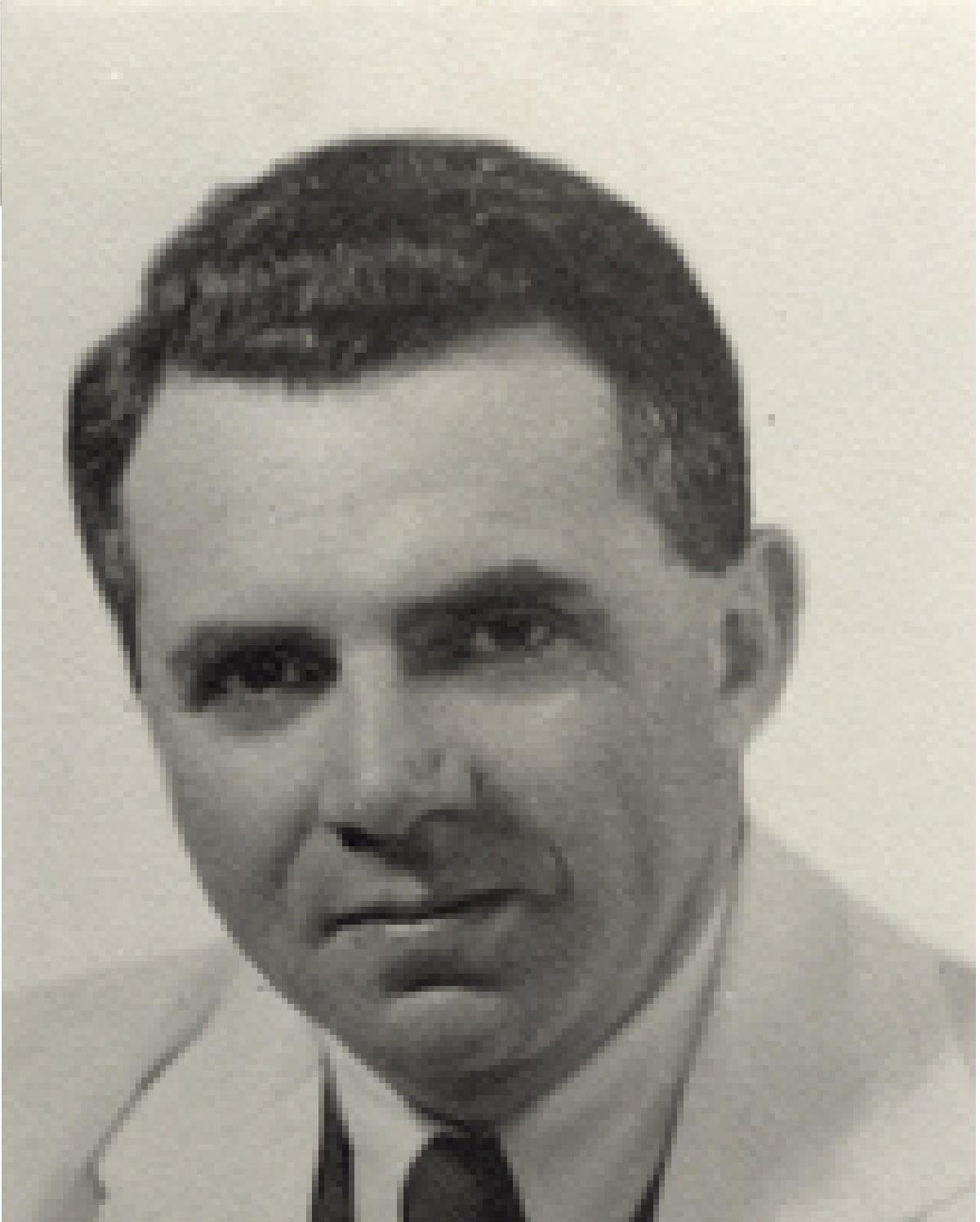

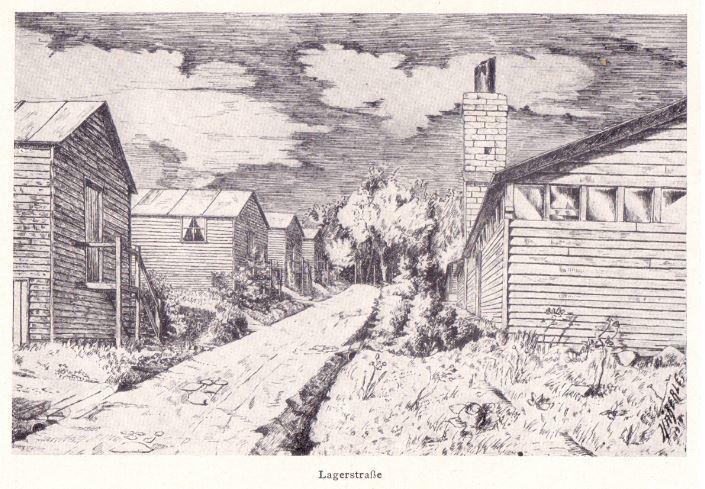

SKIPTON was second lieutenant Robert Bloch’s fifth prisoner-of-war camp.

He only stayed for six months, but these six months would be important. Born in the historic town of Nuremberg, Bloch had previously been a medical student. Although he had left the camp by the time the influenza pandemic arrived in February 1919, Bloch had shared the camp with thirty-five of the forty-seven prisoners who would eventually die from the disease. When he was finally released and had returned to Bavaria to finish his studies, he decided to specialise in pulmonary medicine.

The British authorities were responsible for breaches of camp security such as escapes or unacceptable behaviour towards the British guards. Bloch served two stretches at Chelmsford Prison. It is not known what offence he committed at Skipton. The assistant commandant was a tall, thin man with an aristocratic bearing. The German officers nicknamed him ‘The Graf’ or ‘The Count’. The German memoir ‘Kriegsgefangen in Skipton’ tells us that at an evening roll-call one prisoner was heard to utter the similar-sounding ‘Giraffe’. The officer concerned protested his innocence, but still had to spend time in a real prison.

Bloch was Jewish. Almost a hundred thousand Jews served in the German Army during the First World War. There was a widespread suspicion that Jewish soldiers were not pulling their weight and that they tended to be in administrative roles rather than serving at the front. The notorious Jewish Census of 1916 was supposed to provide the proof that Jewish soldiers were shirking their responsibilities towards the fatherland. No evidence was found to back these claims, but the results of the survey were not made widely known. Almost eighty thousand Jewish soldiers served at the front and twelve thousand lost their lives in the conflict.

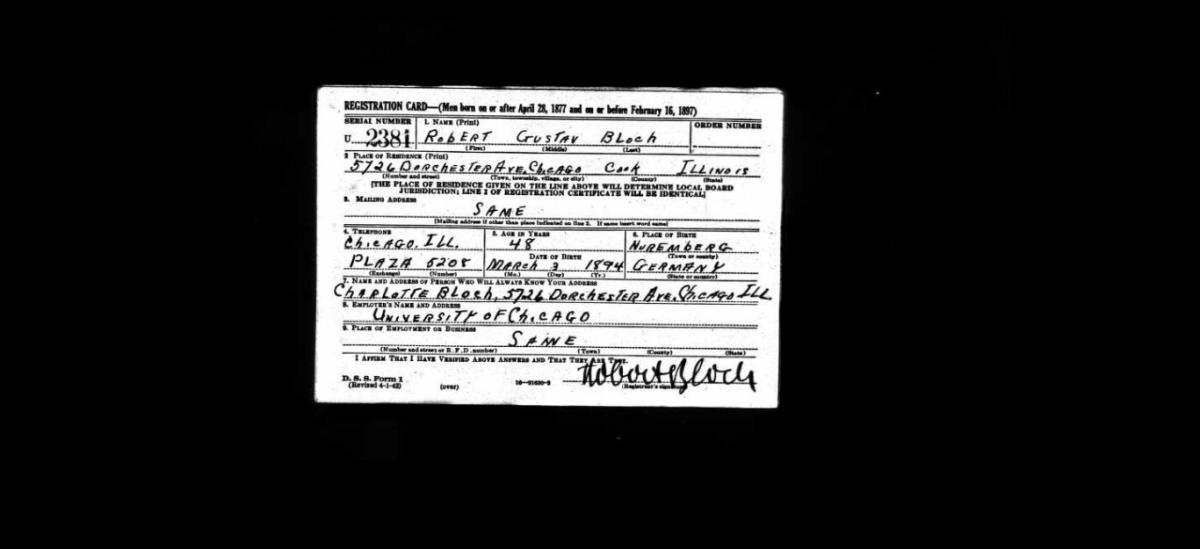

Having completed his studies at the University of Munich, Robert Bloch would sail for America aboard the SS George Washington. He arrived in New York from Bremen on 1 October 1923. The following month Adolf Hitler would launch an ill-fated coup attempt in the Bavarian capital. Munich was no place for a newly qualified and ambitious young doctor where loose alliances of armed right-wing, anti-Semitic nationalist groups seemed to have been doing pretty much as they pleased. A year later Hitler would be placed on trial, and a middle-aged German writer called Thomas Mann would publish a novel called ‘The Magic Mountain’ which was set in a sanatorium located high in the Swiss Alps. Mann would later receive the Nobel Prize for Literature for his work.

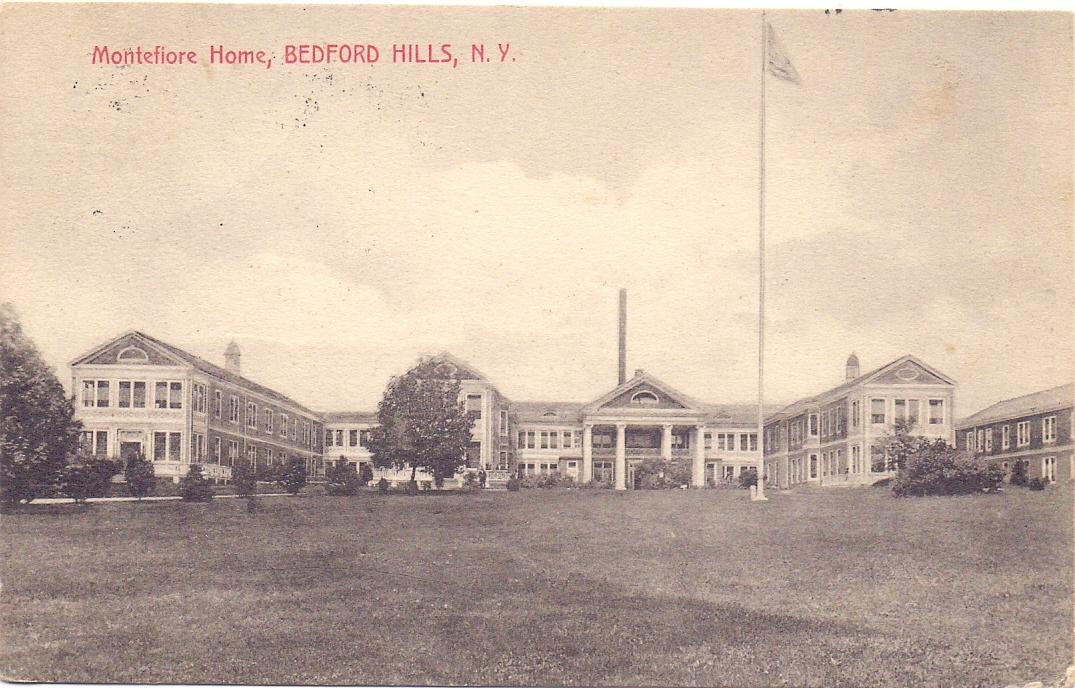

Meanwhile Bloch was now working as a resident physician at the Montefiore Sanatorium in New York State treating patients who were suffering from tuberculosis. At the time it was felt that a restful environment, good nutritious food, careful medical supervision and clean air would all help keep the disease at bay. In fact there was still no effective medical cure for the disease.

Two years later Bloch moved to the University of Illinois in Chicago, where he began his climb up the academic ladder. Starting as an instructor in 1926 he worked his way to become a professor in 1942. He moved to the Montefiore Hospital in New York City in 1951 where he became Head of the Division of Pulmonary Diseases. He published more than forty scientific papers and was involved in some of the early research into the successful treatment of tuberculosis using antibiotics such as streptomycin. He later became well-known as a physician throughout the United States.

Bloch had already become a naturalised American citizen, and completed his draft registration card at the start of the Second World War, but was not called upon to join up. He was by then almost fifty.

Back in Germany three people who shared an apartment at his old address in Nuremberg died or were killed at Auschwitz. A fourth person had taken her own life. Two of the shopkeepers on the ground floor also perished. Meanwhile Bloch’s widowed mother Sally had emigrated to America before the war broke out.

Nobel prize-winner Thomas Mann had also moved to America following the German invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939. Mann instantly became a prominent member of the exiled German community in Los Angeles. When one of the world’s greatest writers became unwell with respiratory problems, it was only fitting that he should receive the best medical advice from none other than former Skipton prisoner Robert Bloch. And what better way was there for Mann to record his thanks than in one of his autobiographical books?

‘Dr Bloch came in and exercising his authority took over the first general examination from his assistant. His enquiries about the previous medical course of the disease were both friendly and extremely precise. The decision to operate was not taken then and there, but was left pending the results of a bronchoscopy.’

Not perhaps his greatest piece of writing, and a very long way from the wooden huts of Raikeswood Camp. In the words of one of his students:

‘Dr Bloch was a great teacher and a very warm human being.’

There can be no finer praise than that.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here