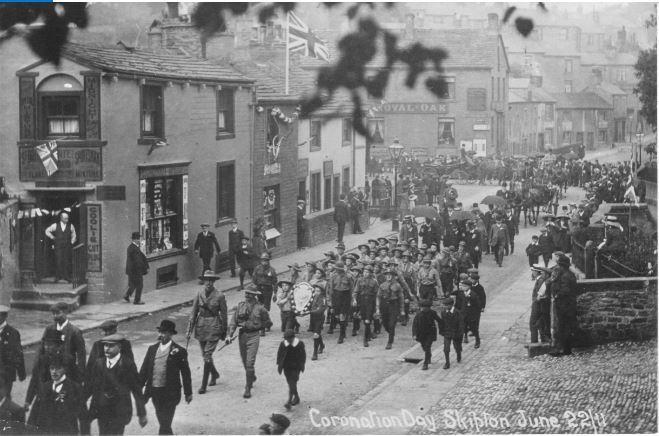

German officers held in Skipton recorded minute details of their lives in the book ‘Kriegsgefangen in Skipton’, writes historian Alan Roberts

Some drew sketches and others opened up their diaries for scrutiny by the historians of the future. Their book was so carefully compiled by its editors. One delayed his return to teaching to work on it, while another took time off from the German Navy. Skipton Camp functioned as a self-governing republic and the British were primarily concerned about what entered and what left the camp (including escaping prisoners)! The German administration extended its long arms into almost every aspect of camp life, and the book was no exception. Expect no salacious details here. The word used for unsubstantiated rumours was ‘latrines’. One officer writing in the book could not bring himself to write the full word because it was too rude and stopped short at l……… .

A footpath passed close by to the camp’s perimeter fence. According to the German officers girls from Skipton took pleasure in using it as an opportunity to promenade. One morning promenade turned to serenade as members of the local Salvation Army performed for the benefit of the prisoners. That was enough and a high screen was built to protect the inmates of the camp from any prying eyes (and vice versa).

The German officers had exercised admirable restraint in describing the behaviour of some of the local womenfolk. However, the Craven Herald reproduced an article from a sensationalist Sunday newspaper the ‘Empire News’. Referring to German officers being escorted on walks through the town centre under guard, it said: ‘To women who have to pass them the situation is embarrassing and all the women in Skipton are not like those who visited the camp and threw cigarettes and sweets to those behind the wire.’

Meanwhile reports of events in Skipton had inflamed great passion elsewhere. The Craven Herald published a letter from Private Davison from Barnoldswick who was serving with the British Army ‘somewhere in France’. He had read about events in and about Skipton elsewhere and did not mince his words. Understandably enraged he wrote: ‘To read in our English papers that English girls are becoming familiar with these fiends is almost beyond comprehension… Is this why we have given up home comforts, yes, thousands of lives and made thousands of widows and orphans? I am a Cravenite and were I to see a German prisoner in company with a British girl I should not hesitate to separate them even if it necessitated force.’

The Craven Herald located in the heart of Skipton had hitherto refrained from referring to the subject because no reliable facts had emerged, or indeed would emerge.

The German officers were pining for the girls they had left behind. Few women matched their visions of classical beauty or the comeliness of a typical German girl. And in Skipton they said that even in peacetime they had never seen so many overweight people before. They particularly remembered the vast girth of a girl at the Royal Oak who, they said, was a true colossus in female form.

They avidly read the pages of the gentlemen’s magazine ‘La Vie Parisienne’ which found its way to them from France. A reporter entering the camp after the German officers had left found, ‘The barber’s shop… was galleried with these exclusive pictures and the responsible organ – sent forth weekly from a Paris publishing house – lay, discarded near the door.’

If the German officers could not see real women they could see some very good imitations! The undoubted highlights of life in the camp were the regular theatrical productions performed in the Old Mess. The officers took great pride in the professionalism of their productions. It was a measure of their resourcefulness and ingenuity. A few officers specialised in performing female roles. Beautiful young ladies were needed even in comedies like ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’ written by Oscar Wilde. Again attention to detail hoped to create the illusion that the world outside did not exist for a couple of hours at least.

The camp newspaper published early in 1919 had none of the reserve of the German memoir. The jokes at the expense of their fellow prisoners were merciless, and locked in a camp there was nowhere to go to find solace. One can only guess at the stories behind the small ads. Lemin & Ramcke were advertising their services as nude models for sculptors and painters. The Kohlenbusch Marriage Bureau was offering its services, claiming to be highly respectable and discreet, and Lore Eisen had broken off her engagement with Herr Wegen. All the names were thinly disguised references to officers at Raikeswood Camp.

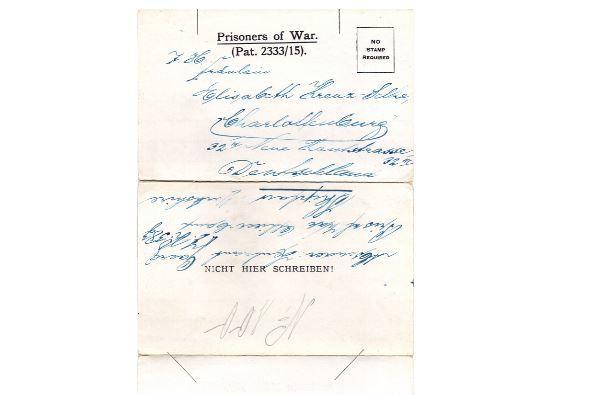

Finally Otto Goerg who was captured at Cambrai in 1917 regularly wrote from Skipton to his eighteen-year-old sweetheart Lizzie. Their love story is being painstakingly unravelled from a collection of letters which has recently come to light. Separation by hundreds of miles during wartime cannot have been easy. How did their romance fare? Some of the letters will go on display in Craven Museum when it reopens this year when all will hopefully be revealed.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel