Henry Robinson, born in 1815 in Lincolnshire, was a cooper’s son who married Epsey Dale, the daughter of a London piano manufacturer who had a significant gene for creativity. Henry became an exceptionally successful solicitor in Settle and, as a result, the family have a huge family tomb in the graveyard. Three sons joined the firm, operating across Craven.

The family lived in the large houses of The Terrace in Settle and had a Georgian house in a Bath Crescent too. Henry left an estate worth the equivalent of millions of pounds today so his children could easily have spent the rest of their lives mixing in high society and enjoying the finer things in life.

However Henry and Epsey were passionate about social and political reform and their children became equality activists. Outside work the sons were local Liberal politicians with ‘indefatigable exertions for the Radical Cause’, as well as excellent cricketers. Son Henry Duncan Robinson enjoyed alcohol and died of cirrhosis of the liver, aged just 31.

Henry and Epsey’s talented and ground-breaking daughters went to Queen’s College, London, aiming to ‘promote a non-competitive spirit to produce confident, open-minded young women’. It certainly achieved that.

Daughter Ann Elizabeth married Francis Atherton who soon after boarded a ship bound for the Australian gold mines and he stayed there. Ann soon became friends with artist Kate Thornbury, living together in Hertfordshire. They became suffragettes and founded the Society of Artists to promote the work of women.

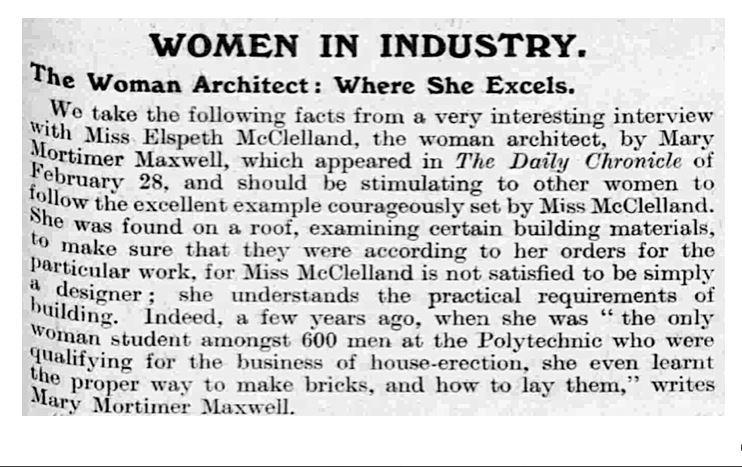

Daughter Epsey married John McClelland, a Scottish accountant and salesman. After fathering a daughter, Elspeth, John spent his life travelling, so Epsey and sister Ann became business partners specialising in interior design, exceptionally unusual for women in those days.

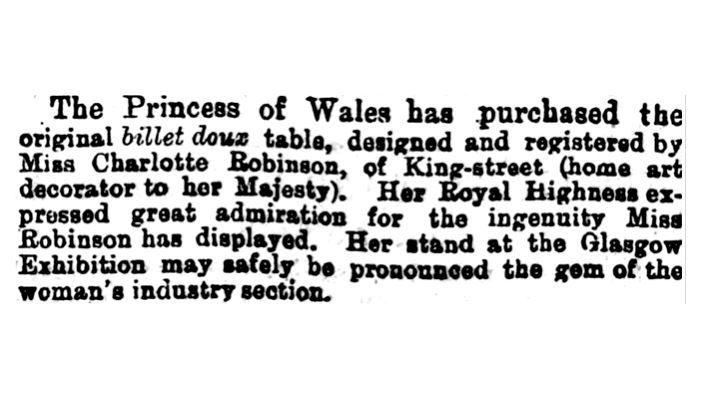

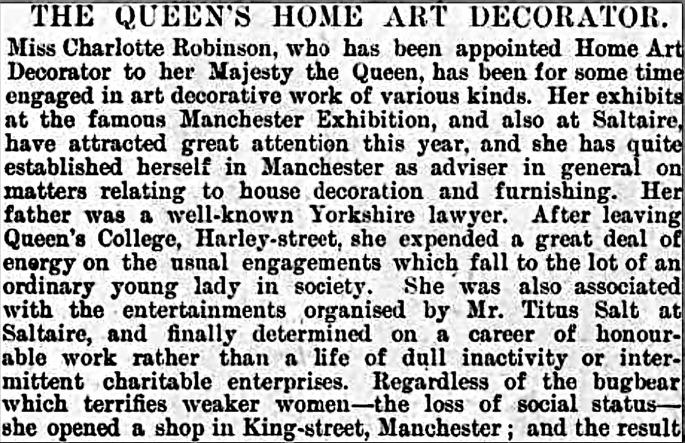

Youngest daughter Charlotte was another artist, exhibiting her decorative designs in Manchester, Glasgow and with Titus Salt at Saltaire. She ‘finally determined on a career of honourable work rather than a life of dull inactivity or intermittent charitable causes . . . Regardless of the bug bear which terrifies weaker women — loss of social status — she opened a shop in Manchester. Incredibly, as a result of her success, she was appointed to serve as ‘Home Art Decorator’ to Queen Victoria. The Queen’s daughter-in-law, the Princess of Wales, wife of Bertie, future Edward VII, was also fond of her work.

‘Her furniture designs are simple and unique; she has dainty and quaint arrangements for cosy nooks and odd corners, and has good reason to be proud of the work of the artists employed in the studio’

Charlotte had met Emily Faithfull whilst at Queen’s College, and they set up business together in London and Manchester. Emily was a vicar’s daughter from Bloomsbury, well known as a ‘petticoat philanthropist’. She was a women’s rights activist promoting girls’ education, women’s employment and suffrage. She published material through her business ‘Victoria Press’, and was also appointed to serve Queen Victoria.

Soon after the divorce laws of 1857, Emily was involved in a high profile case in which she was suspected of being ‘the other woman’ to the wife of naval officer Henry Codrington. Emily was known to dress in ‘manly clothes’. Scandalous! This divorce was recently rated number 2 in ‘Marriage Scandals that Shocked the 19th Century’, and is portrayed in the book ‘The Sealed Letter’ by Emma Donoghue.

When Emily died in 1895, she left her estate to Charlotte, “my final love, as some little indication of my gratitude...for the affectionate tenderness and care which made the last years of my life the happiest I ever spent.”

Charlotte left her estate to her niece Elspeth McClelland who had become one of the first female architects in the country, working in the style of the ‘Arts and Crafts Movement’ inspired by John Ruskin and William Morris promoting simple, romantic and traditional craftsmanship.

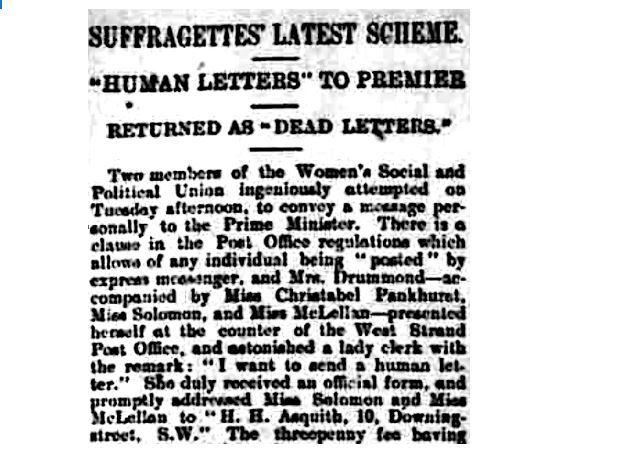

Unsurprisingly, Elspeth was swept into the Edwardian suffragette movement. In 1909 Elspeth became a ‘Human Letter’ along with Christabel Pankhurst. As a publicity stunt they sent themselves as a letter to 10 Downing Street, costing three pence. Downing Street would not sign the postman’s forms so they had to be returned as a ‘dead letter’. Ironically, in the same year, Settle Conservative Club ran a debate on woman’s suffrage but ‘after a warm discussion’ voted against giving women the vote.

Quite a spectacular family!

For full stories and information look up ‘Settle Graveyard Project’ or find us on Facebook. Have you any relations buried at Settle? Please get in touch, we’d love to hear from you. Sarah Lister, settleresearch@gmail.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here