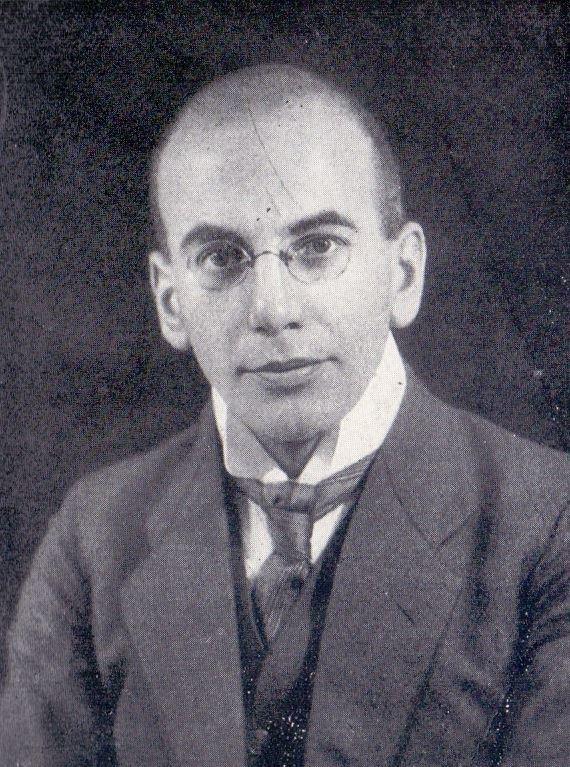

ARCHAEOLOGIST Walther Bremer relished the thrill of serving his country during the First World War. Alan Roberts looks at his life as a Skipton PoW.

His credentials as an archaeologist were already impressive: an accomplished excavation of a Stone Age village in central Germany, a doctorate where he had studied the hair styles in ancient Greece, and a travel scholarship to the Mediterranean to conduct his own research. Now a prisoner he resented ‘his’ important work being disturbed by meaningless roll calls which took up several hours of his time each week. His talent was recognised within the camp: ‘That fascinating head next door is quite simply a piece of genius that has been captured in a human form. It is a future professor of archaeology. The hand that you see so diligently at work, is currently writing exceedingly learned articles about those Stone and Bronze Ages that seem so fantastic to us today.’

His burgeoning reputation was also spreading outside the camp. Distinguished British archaeologists Sir Arthur Evans and Duncan Mackenzie were able to assist him in his vital work. This boded well for the future: international cooperation by leading experts for the good of humanity. Bremer considered his time in the camp to have been extremely productive.

He returned to Germany to further his career. The prediction made at Skipton was to come true when he was made Professor of Prehistoric Archaeology at the University of Marburg.

Ireland had gained independence with the formation of the Irish Free State. The new country was keen to stress the international importance of its collection of artefacts held in the national museum in Dublin. Accordingly the vacant post of Keeper of Antiquities was widely advertised throughout Europe. The successful candidate was Skipton prisoner and German national Walther Bremer.

Bremer approached his work with ‘all the proverbial thoroughness of his nation’ and personally inspected every single one of the thousands of objects held in the collection. In one of four ‘epoch-making discoveries’ he proved beyond doubt that there were links between Ireland and Spain in prehistoric times. He wrote over twenty scientific papers and made over a hundred contributions to an encyclopaedia of archaeology which included items on three locations in Yorkshire.

Bremer was not seduced by any of the bogus scientific knowledge being bandied about by some political parties and nationalist groups about the origin of the German people.

Sadly Bremer would die just nine months after taking office. He had suffered from brucellosis caused by eating unpasteurized dairy foods when working in Greece. According to one former colleague, this was ‘a serious loss for science in general and for Ireland in particular it is a catastrophe’.

In a strange twist of fate, Raikeswood Camp, where Bremer had spent twenty-one months as a prisoner, would itself become the subject of three archaeological excavations on ground which had not previously been built upon. The digs were conducted by both accomplished archaeologists and youngsters from local schools. A large number of artefacts were found including many strands of barbed wire and numerous fragments of broken crockery and clay pipes. Sadly the site had been considerably disturbed over the previous hundred years which made the archaeology extremely difficult to interpret. The final year’s excavation included digging test pits in a number of local gardens.

Bremer’s presence in the camp had been greeted with enthusiasm. Pride of place must go to the New Year edition of the camp newspaper where an imaginative article reports the progress of an archaeological dig conducted in the year 4000. Skiptonians will be reassured that not only were the church and castle still standing, but so too were the mill chimneys, while rows of terraced houses were still belching out smoke into the atmosphere. On a hillside to the north of the town a large settlement had been excavated. The remains of regularly placed 4-metre-high wooden posts had been discovered which were connected by strands of wire reinforced with spikes. The houses were all the same size, and all were made from wood. The inhabitants must have been extremely hardy as the only method of heating was a small stove.

One day something shiny and green caught the eye. A wooden stage was exposed complete with scenery. A picture of an Indian dancer was retrieved unscathed from the rubble. This was a stage backcloth. The experts deduced that artistic enterprise had thrived in the colony’s heyday. Interpretations of other ‘finds’ were however delightfully wide of the mark.

The anonymous author clearly enjoyed writing his fictional account. He also fabricated several documents including Raikeswood Camp’s own Ten Commandments e.g. ‘Thou shalt treat thy neighbour with due reverence in the early hours of the morning’ and ‘Thou shalt not shorten his beauty sleep by any heavy breathing.’

This time the German prediction was overoptimistic. Recent research has shown just how quickly the signs of the camp Have disappeared from both above and below ground level.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here