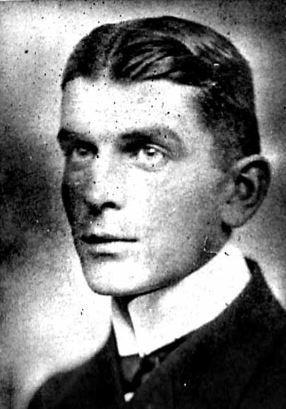

A German U-boat commanded by a Skipton prisoner had been hit by a torpedo fired from a British submarine. Historian Alan Roberts investigates the short life of former Raikeswood Camp detainee Claus Lafrenz.

It was sheer bad luck. British Naval Intelligence said Claus Lafrenz had been overconfident. He had seen the submarine half an hour before. He was in a hurry to get back to base to start his leave and was looking forward to shooting some hares and ducks on his island home.

The force of the explosion blew him high into the air causing severe bruising to his chest when he landed. Over twenty crewmen would perish and only a handful would survive. U-boat prisoners were routinely interrogated by British Naval Intelligence at Cromwell Gardens which was immediately opposite the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington.

The original buildings have since been demolished but can be clearly seen in old photographs. High-profile prisoners may have been held in central London as human shields to deter enemy bombing.

Released from captivity in October 1919, Lafrenz returned to a very different Germany. The Kaiser had abdicated and left for exile in Holland. In Berlin a republican government was hanging on to power. Lafrenz’s response was to join the Third Marine Brigade, one of the notorious right-wing Freikorps units which had recently been formed. Lafrenz’s unit supported an unsuccessful coup d’etat when the legitimate government was forced to flee the capital. Shortly afterwards it protected that same government by crushing a left-wing uprising in Germany’s industrial heartland of the Ruhr. Lafrenz’s unit was disbanded, but all those who wished were free to join the fledgling German Navy.

Fourteen U-boat officers were held at Skipton. Four would die during the influenza epidemic, and four joined the Third Marine Brigade before entering the official German navy. The Treaty of Versailles had in fact banned Germany from owning any submarines.

Lafrenz was placed in charge of a flotilla of torpedo boats, before taking command of the training ship ‘Niobe’ and lecturing at the German naval college. He left the service in 1925 with the rank of lieutenant commander, and returned to his home on the island of Fehmarn to live the life of the country squire and manage the family businesses of forestry, agriculture, shipping and fishing. He was also the third generation of his family to become mayor of Burg the island’s main town. Life might have appeared to be idyllic, but storm clouds were gathering. The Nazi (National Socialist) party had now come to power, and was keen to flex its muscles.

It was decreed by Hermann Göring the Prussian interior minister that all town halls should display the swastika. Lafrenz refused because he believed the swastika was purely a political symbol. What happened next is symptomatic of what was happening throughout Germany. Just 3,000 people or half the island’s population lived in Burg.

Lafrenz could be confident. His group was the largest in the town council. To take control the Nazis would need to whittle away at his majority and besmirch his reputation. Uniformed Nazi sympathisers were already patrolling the streets. Raids, confiscations and house searches had already begun. Two of Lafrenz’s supporters suddenly changed their allegiance to the Nazis. The socialists had understandably not been attending council meetings: it was then announced that two National Socialists would take their place. In just four short months the Nazis had gained a majority and a new mayor was elected.

Lafrenz had been increasingly sidelined. He was originally elected for six years until March 1937. Early the following month Lafrenz was found dead. The official verdict given by a Nazi-supporting official was suicide, but the island rumour mill had gone into overdrive: he had shot himself, he had drowned, or else mysterious men in black had been seen nearby. There was no police investigation into the death of such a prominent citizen.

The island of Fehmarn could now step into the National Socialist limelight. Heinrich Himmler, the Head of the SS, was made an honorary citizen of the island. Reinhard Heydrich, one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany had married a local girl. The island press reported:

‘A man famous throughout the whole of Germany will visit, someone who is part of the inner circle of our people’s chancellor Adolf Hitler. He is SS Reichsführer Himmler…Outside in the streets there are flags and bunting everywhere. We hope our dear guests will feel really comfortable here.’

Heydrich was also chairman of the Wannsee Conference held near Berlin in 1942 which formalised the deportation and genocide of all Jews from Nazi-occupied Europe. In May that year Heydrich was assassinated by British-trained members of the Czech army in exile.

The local press had been quick to lionise its Nazi celebrities. It is only recently that a plaque has been placed in the town hall wall in Burg in Lafrenz’s memory.

As the German prisoners departed for home the words of Senior German Officer Fritz Sachsse resounded in their ears, ‘Together we will rebuild the Fatherland’. Never in their wildest dreams could they have imagined what was to happen, and sadly Skipton prisoner Claus Lafrenz was to be the camp’s first victim of Nazism – one moment of opposition had ultimately cost him his life.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here