British guards at Raikeswood camp were drawn from ranks of soldiers who were unable to see action. Historian Alan Roberts writes.

THE songs of the British Tommies have become part of our DNA: ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ and the breathtakingly simple ‘We’re here, because we’re here, because…’ which perfectly captured many soldiers’ views of life in the Army.

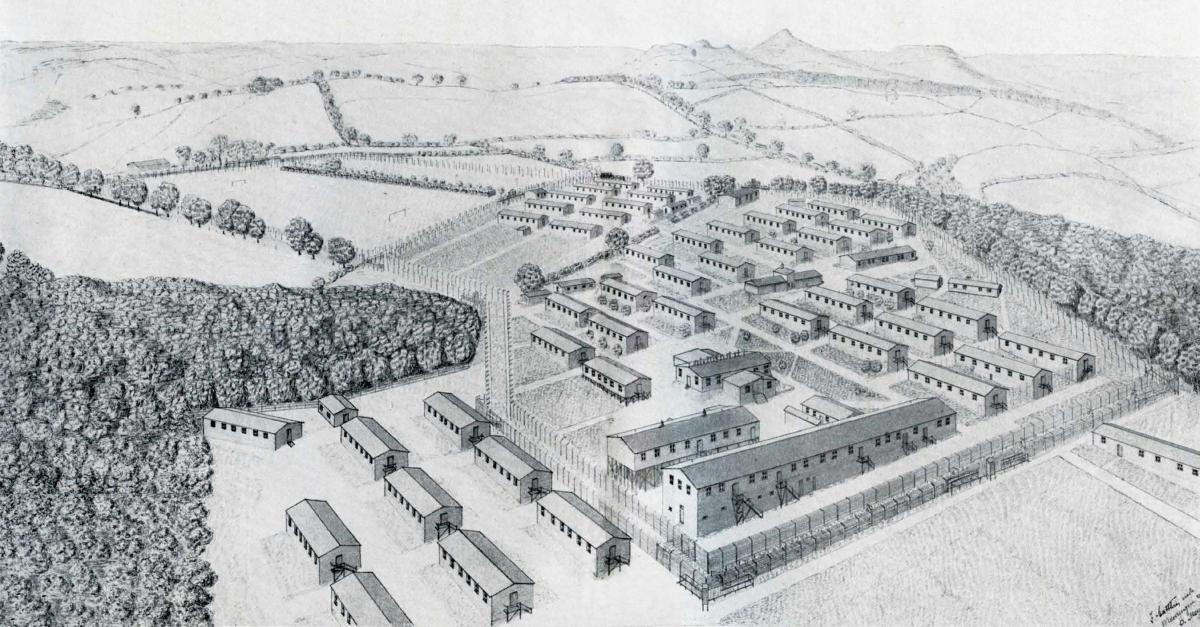

Spare a thought for those who were unable to join their comrades abroad due to advancing age, wounds or ill health. It was from their ranks that the British guards at Raikeswood Camp were drawn.

Private Robert Taylor, a french polisher of Penny Street in Lancaster, was serving with 153rd Protection Company of the Royal Defence Corps.

This was a unit of the regular army rather than a First World War equivalent of the Home Guard. He was 56 years old in 1918 and had been placed in health category B3. He was considered fit for service abroad, but only as a clerk or storeman.

His son Wilfrid had served in the Cumberland and Westmorland Yeomanry. A photograph taken in the summer of 1914 shows Wilfrid resplendent in his cavalry uniform at a horse inspection in Penrith.

The unit would lose its horses and many of its men. Wilfrid too was killed in action in France in August 1918 just 80 days before the fighting on the western front would cease. He was just 23 years old.

The envelopes of two letters addressed to his father at Raikeswood Camp survive: one is postmarked September 1918; the other, sent in November 1918, was addressed to Hut 3.

The British guards had to occupy similar huts to the German officers, but with many more men in each hut. Taylor was still at Skipton on New Year’s Day 1919 when he signed a declaration stating that he had not suffered any disability resulting from his military service.

A further letter concerning his son’s death was written to Taylor at Skipton and dated 17 February, but by then Taylor had already been demobilised.

After the war Robert Taylor became an instructor at a centre for the treatment and training of disabled soldiers at Squires Gate in Blackpool.

Rank and privilege offered no protection from the horrors of war. Sadly Harrow-educated Assistant Commandant and war hero, Lieutenant Colonel Eley was to become another grieving father when his son William was killed in France.

Unfortunately not all the guards at Skipton led such exemplary lives. The temptations of the nearby town proved too much for a small minority of them as the Craven Herald would report.

Instructions were sent from the officer in charge of the camp for the arrest of Thomas Rushton.

PC Jacques of the Skipton police visited a house in Waller Hill and found the house in darkness and the door locked. A woman’s voice called out from upstairs ‘All right’.

The prisoner was later found asleep on the sofa, or else feigning sleep.

Superintendent Vaughan warned that anyone absent from the camp after 10 o’clock at night would be arrested and anyone assisting them would be brought before the magistrates.

Later that month the wife of a British soldier being held as a prisoner of war in Germany appeared in court charged with aiding or assisting a British soldier to absent himself from duty.

PC Newsham reported that he had visited an address in Skipton at 12.05am in response to a telephone call from Raikeswood Camp and found Samuel Riley on the sofa.

The woman said that she did not know she had done anything wrong and thought Riley had a late pass.

She was fined 20 shillings.

Riley was a potter who had been born in the East Midlands, and had joined the Sherwood Foresters in 1914.

His son was born in March the following year. Riley married the boy’s mother a few months later.

Riley was later sent to France, but his actual service as a front-line soldier turned out to be extremely short.

On the fifth day he was found to be suffering from an abscess in his right buttock, and was sent back to England for treatment at a hospital in Bethnal Green.

He had been absent from Britain for just 22 days.

The abscess was opened and drained.

He returned to France the following year, but was found to be suffering from a hernia. There was then a suspected case of diphtheria.

Finally he was wounded in action receiving severe gunshot wounds to his left leg and arm. He returned to England on the hospital ship Grantully Castle in late summer.

When the first German prisoners were entering Skipton Camp Riley was being treated for gonorrhoea in Lichfield. He was then transferred to 153rd Protection Company of the Royal Defence Corps on the last day of June, but was destined to stay in Skipton for only two months.

He was absent without leave on three separate occasions within an eleven day period. He was docked a total of 13 days’ pay.

It should be stressed that very few British guards appeared before the magistrates, and there is little evidence that the vast majority were anything but conscientious and professional in the exercise of their duties.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here