Walter Morrison took over Malham Tarn Estate in 1857.

He and the tarn were synonymous. Less well-known were those who ran the estate on his behalf, notably John Whittingale Winskill (agent).

In support were William Skirrow (butler), Miss Lodge (housekeeper) and Robert Battersby (coach and horseman).

The domed chapel of Giggleswick School, crowning a gritstone knoll, was a gift from Walter Morrison, a “grand old man” who was on the school’s governing body.

Morrison was impressed by the architecture he saw in the East.

His famous building is of Gothic style with an Eastern dome.

Visiting the knoll, at the time of Victoria’s golden jubilee, Morrison plunged his walking stick into the ground and announced that it would be the site of the chapel. He would cover the cost of construction.

The mini-mansion at Malham Tarn was Morrison’s “mountain home”. He would travel from his house in Cromwell Road, London, to Settle by train.

Several of the girls who attended to household matters were also allowed to make the north-bound trip. Skirrow, the butler, promised the girls an hour or so in Settle.

They had tea with him. Robert Battersby, the coachman, conveyed them all to Malham Tarn house in a horse-drawn landau.

John Winskill was Morrison’s estate agent. Good-looking and smartly-attired he had the look of a gentleman - and was occasionally taken to be one when his employer was not present.

Winskill updated most of the farm buildings. He installed a fish hatchery at Tennant Gill. Estate and household accounts were carefully scrutinised. When a sheep died, accounts must be debited with a sheep and credited with the fleece of the dead sheep.

Malham Tarn estate included some outstanding heather moorland - among the best-known in Yorkshire. Walter Morrison, who had passed through a school of musketry, was no grouse-shooter but he was a keen marksman who liked to have a gun on his walks and, in later times, even when he was riding. He shot any sporty birds that passed close by.

Sunday services were held in Malham Tarn house, which was kept tidy through the efforts of a housekeeper named Miss Lodge.

A drunken postman arrived at Malham Tarn one Christmastime. Skirrow, the butler, kept him out of sight of Morrison and provided the postman with dinner, allowing him to continue on his round.

When, that afternoon, Walter Morrison decided to have a short ride by horse and carriage, Skiddaw had a distant view of a drunken postman lying in a road-side ditch.

Walter Morrison believed the postman had been taken ill and wrote to Whitehall about the incident, suggesting that the round was too arduous for the postman allocated to it.

The late Norman Thornber related a story about how Morrison almost met his death.

While dashing to the station at Settle, he called at a tobacconist’s shop and took from a shelf a jar of what he thought was his customary brand of tobacco.

The tobacconist was startled to discover that his wealthy customer had not taken his usual brand but a drug called latakia, which was used in minute portions to curb bleeding. The railway company contacted Morrison and - just in time - took the latakia from him.

At the time, Morrison was filling his pipe for a quiet smoke.

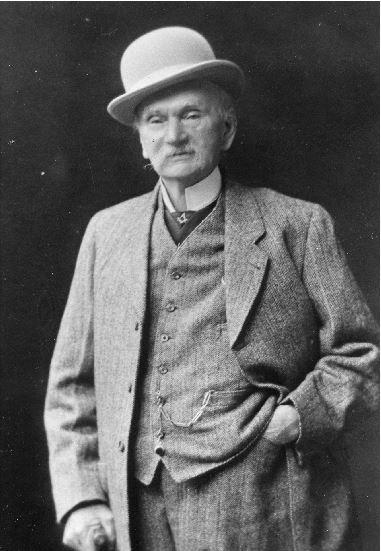

Walter Morrison did not aspire to national fame though some of his deeds were of national renown.

He became chairman of the railway in Argentina. Another time, he selected a young lieutenant to accompany the Palestine Exploration Committee.

The young man became renowned as Lord Kitchener.

After the First World War, Morrison paid for the book, Craven’s Part in the War.

Thomas Brayshaw had been urged by Morrison to produce his history of the Settle district, another classic work. Brayshaw drew his information from a scrapbook and, as a solicitor, from lots of old papers.

Glittering prizes were offered to him but were not accepted.

Norman Thornber wrote: “He lived and died plain Walter Morrison.”

He owned Malham Tarn estate for over 60 years. His love of Malhamdale led him to cover the cost of restoring Kirkby Malham Church where his grave lay.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here