While coronavirus continues to sweep the globe, historian Alan Roberts looks at the flu virus which rampaged through our area over 100 years ago.

Much has been written about the German prisoners held at Raikeswood Camp and the loss of 47 of their comrades during the influenza outbreaks of 1918 and 1919, but how did the townspeople of Skipton fare and were their daily lives as disrupted as ours have been in the last eighteen months or so?

A young farmer in Kansas had become infected by animals he was handling. Herded together in huge army camps the size of small towns the virus rapidly spread among the raw recruits who then carried the disease across the seas to Europe. The newspapers remained silent. News of the epidemic could damage morale, or prove useful to the enemy. When the king of Spain became ill, the press broke its silence and ‘Spanish flu’ hit the headlines.

People in Skipton wondered what all the fuss was about. That was set to change. The Pioneer reported that healthy people one minute found themselves completely ‘bowled over’ the next. Eighty employees at Belle Vue Mills had been absent from work the previous Monday. Two local doctors and several children had caught the disease, but no schools were closed. The symptoms were a high temperature and headaches: most people who caught it were under thirty and recovered within two days.

The Craven Herald advised that rinsing the mouth and nostrils every morning with a lukewarm solution of salt was a very good precaution against the disease. Another good measure was to get as much fresh air as possible. Quinine was known to prevent the malady, but there was the likelihood of a ‘run’ on the medicine and local chemists might run out of stock.

Unfortunately Dr Atkinson, the Medical Officer of Health later reported that six civilians had died including two brothers. In five cases the disease was complicated with pneumonia and the remaining case by bronchitis.

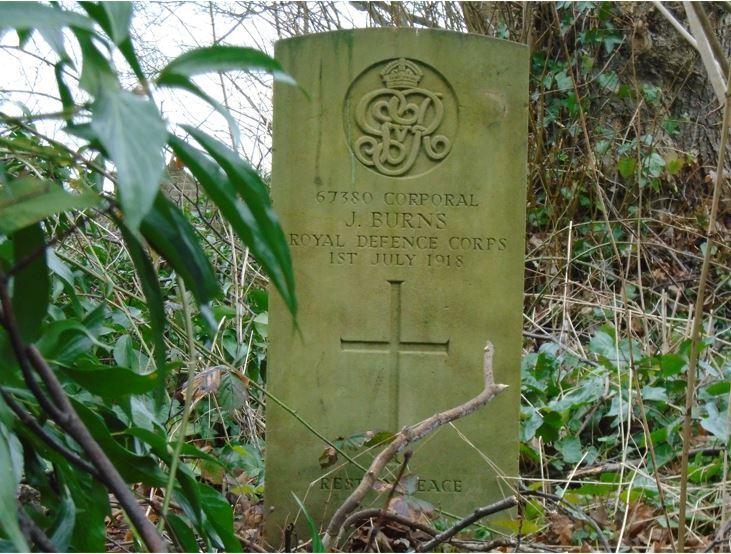

Meanwhile at Raikeswood Camp a number of German officers had been admitted to hospital. Several deaths were reported among the British guards included Corporal John Burns from Barrow in Furness. He had been a very smart soldier and was held in high esteem by his officers. He had been sent back from the front suffering from poison gas and shell shock.

In Barnoldswick 57-year-old Mrs Bailey whose husband ran the greengrocer’s in Rainhall Road died from pneumonia developed after she had caught the influenza virus.

Fred Pickles, an engineer at Acre Shed in Cowling died after an attack of influenza. He had been in poor health for some time. He had been an accomplished musician, music teacher and piano tuner.

Enterprising Skipton chemists Taylors had taken the opportunity to take out front-page advertising for ‘Hunter’s Fever Cure’ to ‘keep away and to remedy influenza’. As the disease abated in August their adverts retreated to the inside pages.

The authorities had been placed in a difficult position. The great German spring offensive had ground to a halt, but the war had not been won. The first day of the Battle of Amiens in August was described by one German leader as a ‘black day for the German Army’. The battle itself resulted in tens of thousands of casualties on both sides.

Arthur Newsholme, one of the government’s leading health experts had prepared a series of guidelines for public use including isolation of the sick, avoiding crowded places and not spitting in the street. They were not distributed. ‘There are national circumstances,’ he wrote, ‘in which the major duty is to carry on. The relentless needs of warfare justify the risk of spreading infection.’ The famous poster ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ would not appear until twenty years later.

It would be left to local medical officers of health like Dr Atkinson to balance the needs of a country at war with those of a town in need.

The influenza epidemic had not been defeated. The virus had mutated and the new variant spread rapidly across the globe from another American army camp near Boston. The following month the virus had reached Embsay, before spreading to Skipton and Carleton. This new variant was much more severe and more widespread too. The onset of the attack was sudden with high temperatures, catarrh, pains in the back and limbs, and in the worst cases bronchitis and pneumonia. In some cases whole families were affected. Mill workers were more likely to be infected than others. The disease mainly attacked young adults. There were fewer cases amongst young children and the elderly.

Action was taken swiftly. Schools were closed in early November. No children under 14 were to be admitted to the two picture palaces in Skipton. Posters warned of the dangers of attending large gatherings of people, especially dances.

These measures seem mild compared with our own experiences, but would they be sufficient to stem the tide of a disease that would eventually kill many millions of people across the planet?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article