The flu pandemic which hit the district at the end of World War 1 crippled the nation. Here historian Alan Roberts presents part two of three reports.

The new year dawned promisingly. It was 1919 and the war was now over after more than four years of bitter fighting. Schools which had been shut since early November because of the influenza outbreak had just reopened. Attendance was reported to be good, but official figures were not available.

The medical officer’s report was a feast of interesting information. The population of Skipton was 11,204. The highest point was Rombalds Moor at 1200 feet and the lowest was at the sewage works (315 feet). At 30.66 inches, rainfall measured at the town hall was slightly below average. Cotton-spinning and worsted-weaving mills where the town’s biggest employers.

But the inside pages told the grim tale of the previous autumn’s influenza epidemic. Two people had died in October, 12 in November and 10 in December. Typically there would be just three deaths from influenza in a whole year. The previous year there had been a total of 30 deaths from the disease, while the overall death rate was fifty per cent higher than usual.

Eleven of the deaths were in young people aged between 15 and 35. Normally the highest death rates in a flu outbreak would be in the very young or the elderly, but this was exceptional. The virus caused what is now known as a cytokine storm where the immune system does more harm than good. It ends up damaging the body’s organs. Young healthy adults with the very fittest and best responding immune systems were the people who reacted worst to the virus.

Scientists of the day did not know very much about viruses and disease. Their efforts were mistakenly concentrated on finding the bacteria responsible for the illness. Dr Atkinson, the Medical Officer of Health, reported that no samples of sputum were taken for further examination.

When questioned by members of Skipton Urban District Council, Dr Atkinson explained that there was a ‘vaxine’ which could only be used in special cases, that there were three germs involved in influenza and that the biggest cause of death was from the bacterial pneumonia which frequently followed the influenza.

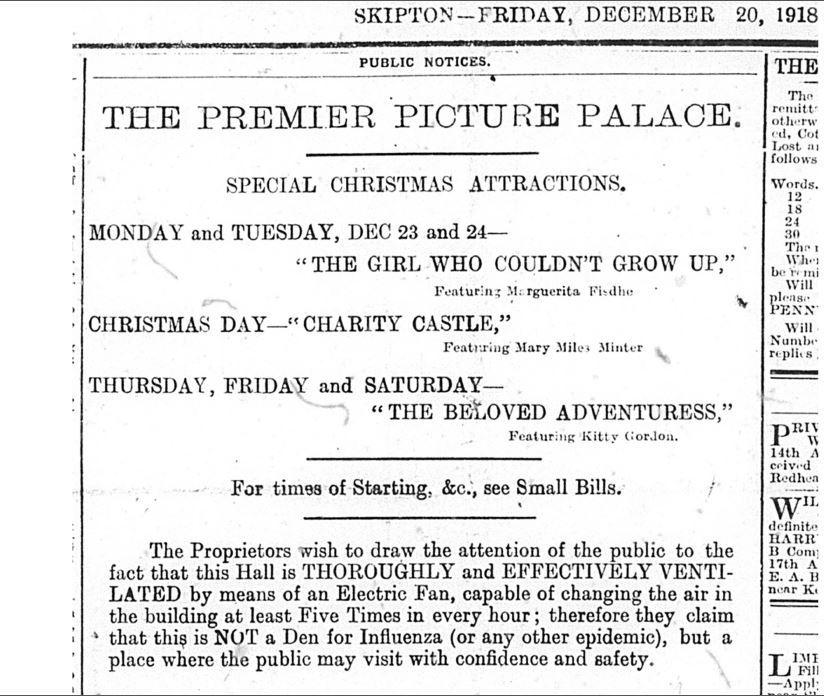

Not only had the schools been closed, but children under 14 had been banned from cinematographic performances at the town’s two picture palaces. The Gem Palace (today’s Plaza) had had one four-hour show and had complied with the order, but The Premier had not been properly ventilated.

Councillor Farey reported that despite the orders from Wakefield – Skipton was in the West Riding at the time – children had still been admitted to the cinemas; the Health Committee had done everything it could to rid the town of ‘this terrible scourge’ and the cinemas were ‘real dens for influenza’. Atkinson said the police would enforce the orders.

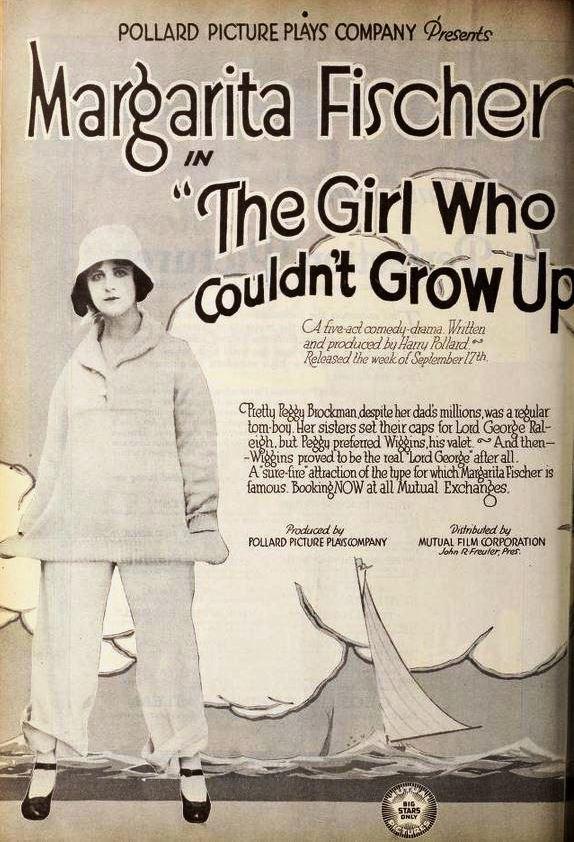

The indignant proprietors of The Premier responded with a front-page advertisement in the Craven Herald: the air, they said, was changed five times an hour using an electric fan and the public could attend in ‘confidence and safety’. Silent movies included ‘The Girl Who Couldn’t Grow Up’ starring Margarita Fischer; the cinema was even open on Christmas Day!

The influenza virus would return in the early spring. In mid-February Dr Atkinson reported that there had been an outbreak in Settle and the local primary school had been closed. Schools in Skipton remained open, but local doctors reported that the disease was spreading.

One Skipton family had lost two children in the previous outbreak, only to lose the mother, father and remaining daughter in this second wave. At Hanlith an ‘exceptionally bright and happy’ eleven-year-old girl had died. At nearby Airton Mrs Richardson passed away leaving a husband and three young boys. She would be remembered for her kind and genial disposition.

A resident of Settle wrote to the paper demanding the immediate demobilisation of Dr Middlemiss from the army in order to relieve the pressure on the two family doctors still practising there. Meanwhile at Raikeswood Camp there had already been 260 cases of influenza and six deaths. Major Parkhurst, the Assistant Commandant, asked that German prisoners of war be admitted to Skipton Auxiliary Hospital. The application was declined on the advice of the medical officer and because the old people normally resident there had been occupying indifferent accommodation to make room for the treatment of wounded British soldiers.

Dr Atkinson emphasised that people should take precautions to stop the spread of the disease. He regretted that the local authorities simply did not have the powers to do more. He advised the public to avoid crowded places and specifically mentioned the new craze for dancing. He recommended gargling the throat, disinfecting the nose and emphasised the importance of fresh air, sunshine and cleanliness. The Craven Herald said whiskey was good at preventing an attack and that medical men advised the public to drink a good claret, if they could still afford to at the exorbitant rates being charged.

They simply called it the ‘Scourge’. There seemed to be no cure and little hope of avoiding infection. Where and when would it all end?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here