Robin Longbottom explains how Silsden once played a central role in the making of clogs, producing the irons that were nailed onto the soles

FOR just over a century, Silsden was a centre for making the horseshoe-shaped irons that were nailed onto clog soles.

Clogs were generally for outdoor wear and to give the wooden soles added protection, they had metal strips nailed along the outer edge – known as rings, or ring irons.

During the early 19th century, instead of nailing iron to the sides, metal strips – bent to the shape of the heel and sole – were developed and nailed to the bottom of the clog and by the 1840s they were much in demand.

The man credited with bringing the trade to Silsden was George Baron.

It is said that he had learned to make them in Colne in Lancashire. However, he had originally been a Silsden nail maker and there is little evidence of any clog-iron making industry in Colne.

Having followed his father into nail making, it may well be that George Baron simply saw a business opportunity and turned his smithing skills to make clog irons.

He started his business in the 1840s and by 1850 he employed nine men, and such was the demand for his clog irons that ten years later he had a workforce of 20 men and 20 boys.

It is unlikely that his employees were working under a single roof, but more probable that they worked in their own home forges.

George Baron would have supplied them with the mild steel rod, and they would have shaped the clog irons and punched out the nail holes using hand tools.

Several different shapes of clog iron were made – the duck toe, for a more pointed clog, was favoured in the Keighley and Craven area.

A round toe iron, known as a common toe, was largely used in industry, such as foundries, tanneries and quarries. In many of the coal mining areas a square toe was regarded as essential as a miner was able to kneel, balance the square toe on the ground and rest his haunches on the heel of his clog while he worked.

A heavy clog iron, known as a Colne strong iron, probably because they were in demand in Lancashire, was a much thicker and slightly more expensive type. To get better wear out of a working clog the irons were often doubled-up by nailing a child’s clog iron inside the other.

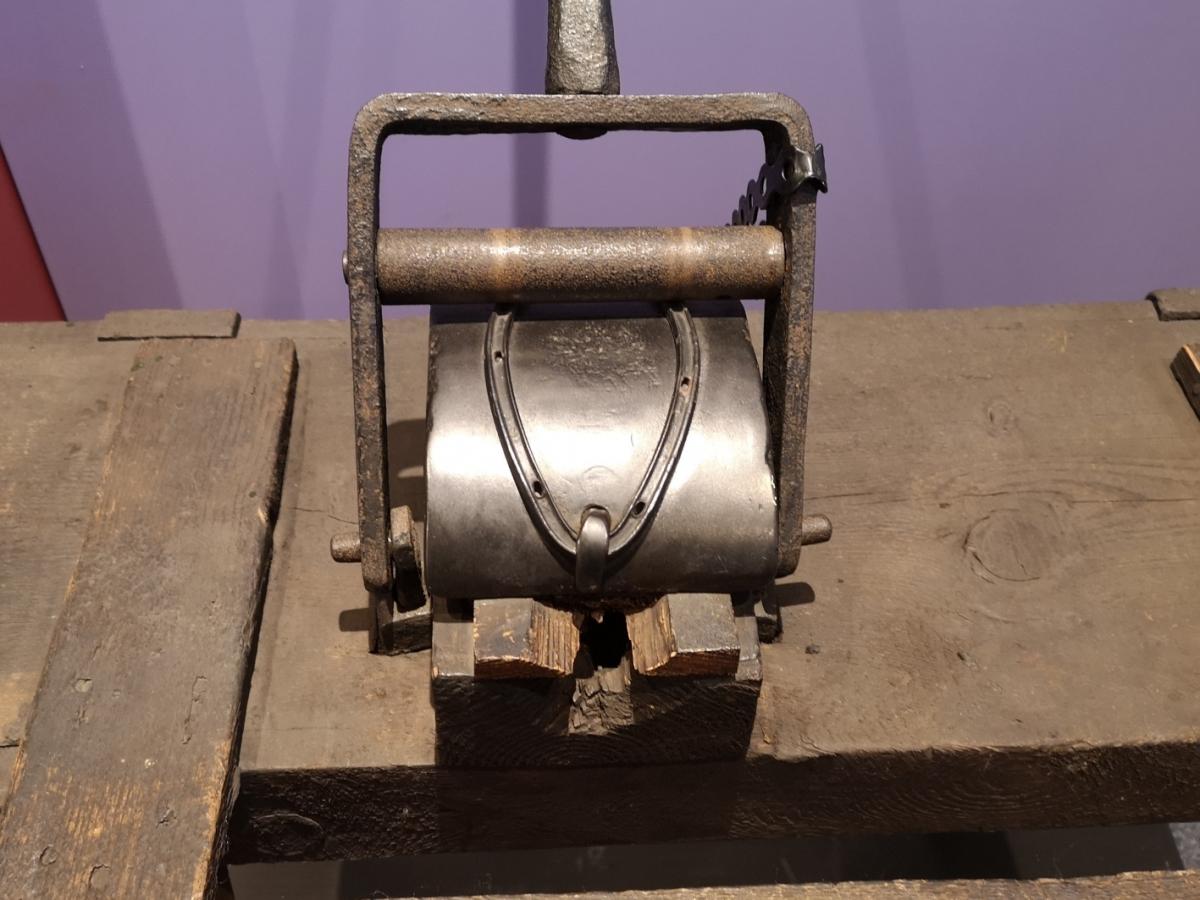

During the latter half of the 19th century, clog-iron making became more mechanised, with the introduction of hand-operated shapers, cutters and punches. These simple machines required fewer skilled men and increased output.

By the 1880s, George Baron – then in his 60s – had reduced his workforce to five men and two boys.

A fervent Primitive Methodist, his son had gone into the ministry and there was increased competition from other clog-iron makers, such as Thomas Green.

It was probably Thomas Green who brought production under one roof after he set-up his workshop in Sykes Lane in 1874. Here he was able to oversee his workers and employ the men on a production line basis – some forging the iron, whilst others shaped it on formers and punched through the nail holes.

The business remained in the family for three generations, however Thomas’ grandson – Charlie Green – eventually found that he was unable to compete with the automated clog-iron makers. In 1950 he ceased production and donated the forges and much of the clog-iron making equipment to the museum in Keighley.

The final words on clog-iron making must go to one of Green’s old employees who when asked if he had enjoyed his work, replied “it wor a’reight but it maks thi shackles wark” – it was alright, but it made your wrists ache!

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here