IT being ‘Salmon Sunday’ at the weekend, I was off again to Paythorne, near Gisburn, on my one person efforts to recreate the generations long tradition when thousands of people would gather to stare into the Ribble.

Every year as I approach the bridge in its hollow I like to imagine what it must have been like when the road was jammed with chars-a-banc, cars, cyclists, pedestrians, and ‘pop-up’ cafes, all clamouring to see salmon performing their acrobatics.

There were a couple of cars parked nearby, but no crowds on the bridge. I did however see a farmer who was off to check on his sheep on his quad bike; he paused and we chatted about Salmon Sunday - he’d not seen any salmon at all this year so far, but pointed out to me the spots, both upstream and downstream from the bridge, where he knew the salmon spawned. He kindly went off, checked and reported back, no signs - I’ll have to return this weekend.

So, looking back to the Craven Herald in 1927 and the closest edition to Salmon Sunday - the Sunday nearest to November 20 - the paper reported on the ‘picturesque old-time custom’.

Every year, the inhabitants of Gisburn and Hellifield made their way to the bridge to perform the ‘solemn rite of staring over the parapet into the dancing stream below in the fervent hope of catching sight of running salmon’, reported the paper.

Paythorne was it seemed, the only place where such a custom took place. A Dr Holder, an American authority on fishing, even included it in his book: The Game Fishes of the World.

One theory of how Salmon Sunday started was that it went back to ‘lawless times’ when poaching was rife and the run of spawning fish was the signal for ‘wholesale raids with spear and muck fork on the hordes of helpless and ill-conditioned fish wallowing on the shallows’.

Such ‘ill-gotten’ additions to the larder, said the Herald, would have formed a substantial item in the household. Later, following the application of fishery laws, the ‘bands of raiders’ would assemble on the bridge about the time of the annual run to ‘mourn over the wasted opportunities and to air their grievances’.

But, continued the paper: “In the remote districts, a spawning salmon in some secluded but accessible shallow nook is never absolutely safe so long as a hefty agriculturalist and a convenient hay fork are close-by.”

Observance of Salmon Sunday gained such a firm hold in the area, that it came to rank as an important landmark in the local calendar - the same as the village feast or indeed the time ‘when we killed ahr pig’.

All day long, a trickle of pilgrims would feed the knots of the faithful on the bridge. Police were detailed for special duty while natives who had migrated to other localities and friends from West Riding and Lancashire towns arrived in shoals to ‘partake in the ceremonies’.

And so the usually peaceful bridge in its hollow was transformed for the one day in November to a meeting place for thousands.

The same as now, it often happened, said the Herald, that ‘Salmon Sunday’ was not in fact the best day to see the fish - an absence of floods leaving the salmon lying in the deeps below, waiting for a rush of water to allow them to negotiate the shallow stream in their upward progress.

When this happened, those staring over the parapet were disappointed, but another year, when the conditions were right, there would be plenty of lusty salmon to watch.

As for Salmon Sunday, 1927; wild weather was blamed for a diminution in the number of observers at the bridge - that, and said the Herald, could be blamed on the introduction of other interests in the rural area, adding: “There is a rarity about this curious Ribblesdale custom - an old time link with a picturesque, if speculative, chapter of Merrie England - that would render its extinction doubly deplorable’.

NOW we are emerging out of lockdown, some of us may feel they may need to lose a few pounds - the old work clothes may well be feeling a little tight.

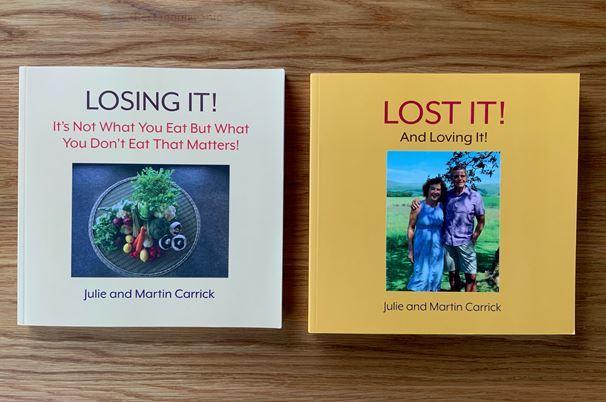

Julie and Martin Carrick, both retired police officers who have lived near Settle for the last 12 years, know a thing or two about losing weight - and have written two books about it.

Neither started out as writers, nutritionists or experts in exercise or fitness- they are just an ordinary couple who wanted to make some big changes in their lives. Back in early 2018, they took a long, hard look at their overweight selves and set out to lose weight, developing their own healthy eating recipes and lifestyle. And it worked - in the next nine months, they lost a combined 12 stones - Julie lost seven, and Martin, five.

Encouraged by friends they first wrote ‘Losing It - its not what you eat, but what ou don’t eat - describing how they did it, with recipes, and followed it up with Lost it and Loving It’

Julie and Martin now talk to groups about how they transformed their lives. To contact them, or buy the books, email julieandmartinlosing@gmail.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here