Historian Alan Roberts continues his investigation into the lives of some of the German prisoners held at Skipton’s Raikeswood Camp during WW1

One name stood out. The War Office had kept meticulous records of all German prisoners captured during the First World War and the name ‘von Schirach’ stood out from the list for Raikeswood Camp:. Second Lieutenant Max von Schirach belonged to an extremely famous, if not infamous family.

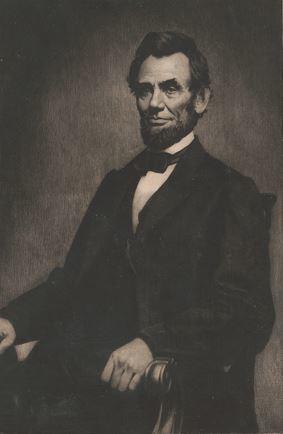

His grandfather Karl Friedrich had emigrated to the United States as a teenager. Badly wounded fighting in the American Civil War he was awarded the honorary rank of major for ‘his gallant and meritorious services’. He was also part of the guard of honour at President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral and had difficulty holding the crowds back as they surged forward in search of souvenirs. He married into a wealthy New England family and was mortified when America entered the First World War.

Karl had two sons. The elder Friedrich Wilhelm was born in America, but returned to Germany to serve with distinction as a cavalry officer in the war. Friedrich was one of three parents of Skipton prisoners known to have been born in the U.S.A. After the war he had become heavily involved in the turbulent right-wing politics around Munich. In 1923 Adolf Hitler and First World War leader Erich Ludendorff led thousands of supporters in an attempt to overthrow the Bavarian government and march on Berlin. Four policemen and fourteen Nazi supporters were killed. Hitler dislocated his arm and was swiftly whisked away to safety

He used his subsequent trial to showcase himself and his ideology to a wider audience. Friedrich was called upon to testify. This prompted a lengthy tirade from Hitler who insisted that he was more than just a ‘drummer boy’ in the burgeoning nationalist movement.

Friedrich’s son Max had been captured near the River Somme on the fourth day of the great German Spring Offensive. He had been born in Karlsruhe on the banks of the River Rhine and lived in the port city of Lübeck. His great passion was his family’s history which he could trace back to the 15th century. In 1939 he was able to publish the fruits of more than ten years of research ‘The History of the Schirach Family’.

Germany was rushing headlong into yet another world war. Von Schirach crowed ‘Our German brothers in the Sudetenland [in today’s Czech Republic] have been brought back into the fold of the German Reich… The memories of the von Schirachs who fought hard for an enlarged and unified Germany in times gone by have received a second burst of life.’ Germany had already annexed Austria, the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had promised ‘peace in our time’ and now part of the former Czechoslovakia had been taken. Alarm bells were ringing across Europe.

The book itself is exceedingly dull – a detailed history with copious family trees and little background material. Fawning tribute was paid to the leader: ‘In this era which has been moulded by the personality of Adolf Hitler, the menfolk of the family have from the very beginning been faithful allies of the Führer’.

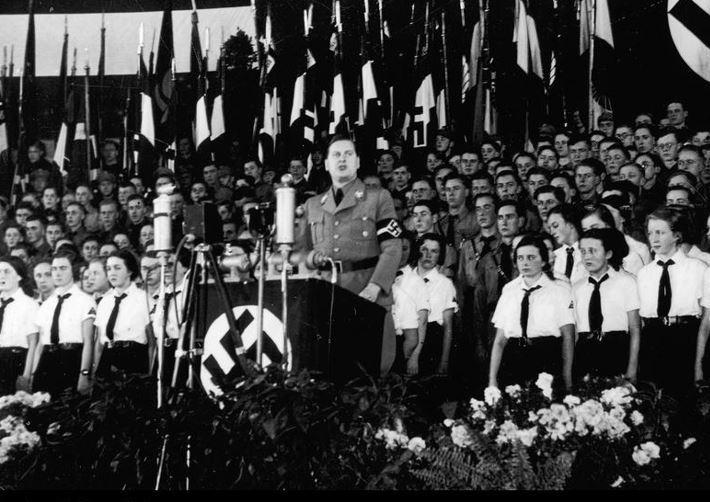

Max’s cousin Baldur von Schirach had rapidly risen to become part of Adolf Hitler’s innermost circle, and head of the Hitler Youth which in 1940 had a membership of around 8 million.

No doubt family connections played a key role in ensuring that Max’s book was published. The favour was not returned. He writes: ‘Today’s generation of von Schirachs are only briefly mentioned… with the exception of the outstanding political representative of the family, Baldur von Schirach, whose name is synonymous with the leadership of the youth of the German Reich. He will not be given particular prominence here, because an evaluation of Baldur von Schirach can only be carried out in the context of a proper historical study of the period in which we live, and this must be carried out by members of a future generation.’

‘May our children and our children’s children grow up in a better time in which they can be proud to be German and by looking back at the lifetimes’ struggles of their forefathers, they too can gain the strength to do their utmost for the German people and their fatherland.’

Many of the German officer prisoners at Skipton were highly intelligent educated men. Yet this book, dull as it was, is still something of a rarity. Max von Schirach cannily leaves the verdict on his highly-placed cousin to the historians of the future, but as the author still bears responsibility for the text.

When Fritz Sachsse, the German Senior Officer at Skipton declared ‘Together we can rebuild the fatherland’, he could have no idea what lay ahead.

Baldur von Schirach later became the Nazi supremo in charge of Vienna. Although no longer part of Hitler’s inner circle, he was still an extremely powerful man. After the war he was sentenced to twenty years’ imprisonment in Spandau prison for his role in the deportation of thousands of Jews to certain death in concentration camps. Astonishingly he was interviewed in English for an ITV programme by a young interviewer called David Frost. Frost later said that this was his most chilling interview ever.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here