Continuing the fascinating look into the history of Raikeswood PoW camp, in Skipton, historian Alan Roberts looks at two British commandants

ALMOST half of Britain’s Prime Ministers were educated at just two schools: Eton and Harrow. David Cameron and Boris Johnson both went to school at Eton and university at Oxford, while Winston Churchill was educated at Harrow and then at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst.

Strangely when Raikeswood prisoner-of-war camp opened in January 1918 its first commandant was Old Etonian, William Chevers Hunter and the assistant commandant was Harrow-educated William Gardiner Eley.

Hunter was born in Kolkata (Calcutta) in 1870, the son of Sir William Hunter a distinguished civil servant and expert on Indian affairs. At Eton College, Hunter came second in the Prince Consort’s German Prize. He then went to Oxford to study Classics. After just two years and with only modest success in his examinations, Hunter decided that university life was not for him. He subsequently trained at Sandhurst before joining the Oxfordshire Light Infantry. His military service included postings to Burma, India and South Africa. His favourite leisure time pursuits included polo and pig-sticking.

When war broke out in 1914, Hunter rejoined the Army and worked as an interpreter in the prisoner-of-war section. In 1918 Hunter would receive his first batch of prisoners as the first commandant of Skipton Camp. Ill health would later cause Hunter to resign his commission with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

The German officers wrote that Hunter was a man of indeterminate character who seemed more at home in the top hat of civilian life rather than a military-issue khaki cap – a damning assessment of a career army officer.

Interestingly the prisoners did not mention that their first commandant spoke their language. Presumably he left all that to his two camp interpreters, one of whom was exceptionally well qualified.

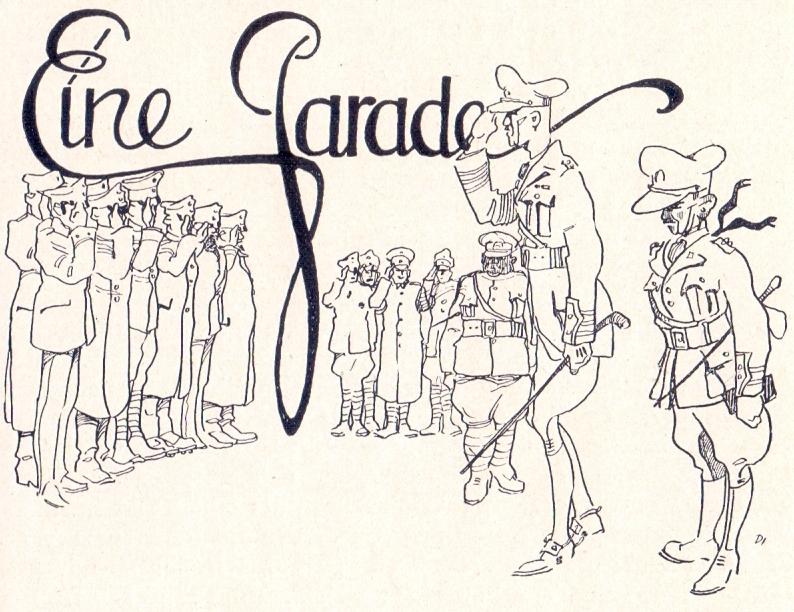

The assistant commandant WG Eley was a war hero, and a reluctant ‘poster boy’ for the German officers. ‘Kriegsgefangen in Skipton’, the German officers’ story of their captivity contained two cartoons of Eley, and long after he had left the camp, he featured on the front cover of the Osterzeitung or camp newspaper.

He was very tall, thin as a rake, and wore a monocle. Eley was a stickler for detail and everything had to be just so. On the other hand a photograph of Eley shows a kindly and well-groomed, middle-aged British officer.

This classy representative of English manhood appeared so aloof that the Germans called him the Graf or the Count. One officer may have uttered the word Graf as Eley inspected the ranks. Unfortunately the British interpreter heard ‘Giraffe’. This was an offence against military discipline, and despite the officer’s protestations he was removed and was reportedly sentenced to several months’ imprisonment.

Eley had previously been mentioned three times in dispatches for his service on the Western Front. Commanders in chief like Sir Douglas Haig produced regular accounts of the progress of the war, which included the exploits of a few gallant men. For the rest, ‘mentioned in dispatches’ simply meant having their names tagged on to a list at the end of the text. Eley was also awarded the Distinguished Service Order in the New Year’s Honours list for 1918; awarded to British officers for meritorious or distinguished service during wartime, when under fire or engaged in actual combat.

Eley had joined the Army thirty years earlier and had served with the 14th Hussars. The ability to move rapidly across the countryside on horseback was a real asset in a cavalry regiment and Eley was an exceptionally talented rider. He later saw service in the Boer War in South Africa before returning home to write his book ‘Retrievers and Retrieving’. The book is available today in a facsimile edition and features a photograph of his own black labrador in the opening pages.

Major Eley rejoined the Army in 1914. Two years later he found himself in command of a cavalry regiment. The massed cavalry attack had become a thing of the past, and his regiment would have to adapt to the realities of industrialised warfare.

Eley was recalled to Britain when he was too old for active service, but was soon given a new role as Assistant Commandant at Skipton. Sadly he also received the news that his son, another former pupil at Eton and cadet at Sandhurst, had been killed in action.

Years later and writing from a fashionable address in London’s Belgravia, Mrs Eley would later query the amount of her widow’s pension. She had firmly been under the impression that her husband had been the commandant at Skipton, and not simply the deputy. Had she been correct? Had Eley been the commandant in all but name? Perhaps we will never know.

There is a fascinating contrast between Eley, who was fastidious in everything he did, and the next commandant, a pragmatist who would simply do what was necessary according to the circumstances.

Meanwhile Winston Churchill was working as the Minister for Munitions. The peace to end the ‘war to end all wars’ lasted barely twenty years. The future Prime Minister would then lead Britain through its ‘finest hour’, but that is another story.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here