Part one of historian Alan Roberts' look at the short life of Emil Jakob Wommer, a German officer PoW at Skipton in WW1 and his early demise from flu.

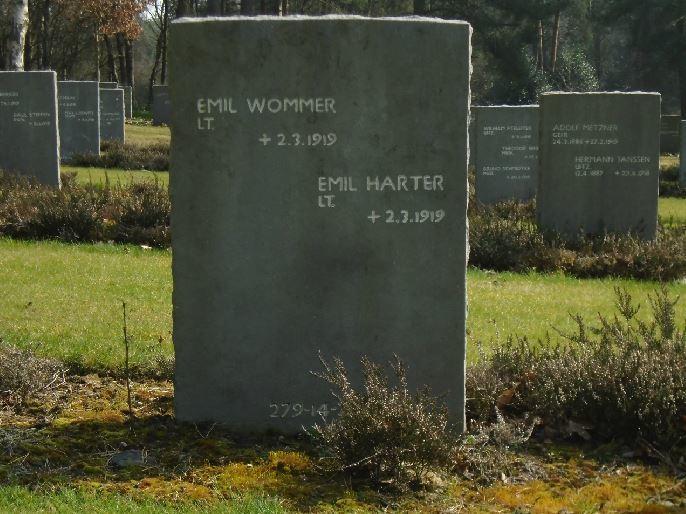

JUST five letters survive from the short tragic life of Emil Jakob Wommer, a young German officer, held during the First World War at Raikeswood Camp, in Skipton, who died at Morton Banks Hospital near Keighley during the flu pandemic of 1919.

‘To be or not to be!’ Early 1916 found Wommer at the front mulling over the rejection of the German kaiser’s peace proposals, and realising that were just two possible outcomes: existence or obliteration, but unlike Shakespeare’s Hamlet he would have no choice in the matter. There would not be a ‘question’ to be answered. Fate would determine everything.

He pleads for the German people, ‘fair Germania’, to remain united. With God’s gracious support we cannot fail to win!

Life had already been hard for Wommer. He lived in a small village in a remote hilly area of Germany. The menfolk worked long hours in the mines and steelworks in the nearby towns, or else kept livestock, or did both.

His father had been an arable farmer, but had died when Wommer was just two years old. His elder sister Frieda had married when she was twenty, but died the following year. His mother followed shortly afterwards leaving fifteen-year-old Jakob an orphan. Somehow or other he managed to stay in school and pass the equivalent of our ‘A’ levels. Meanwhile his elder sister’s husband had married his younger sister, with husband Viktor running the family smallholding and surviving sister Regina opening part of the family home as the village tavern.

Wommer had been enlisted as a private, but by June 1917 he had been promoted to sergeant. Unlike British letters of the time, typically written from ‘somewhere in France’ and subject to strict censorship, Wommer gives exact details of his location. He was based in northern Belgium, separated from the Belgian army by hundreds of yards of newly flooded farmland. Strategically he was positioned on a direct line to the German U-boat bases in Belgium. Ominously the British were reported to be on their way to bolster the Belgian Army. He expects a major offensive to be launched any day. When that happened ‘kaput’ would really mean ‘kaput’, and ‘down the pan’ would really mean.

The days of plenty were over. Bread was the main source of food along with some kind of porridge or gruel created by the army cooks. Bread was in short supply, but at least no-one was starving.

Much of Wommer’s letters is taken up with his homespun philosophies. A deeply religious man he wrote that they should put their trust in God on high and not fear the might of the enemy.

His sister had been unwell and he hopes she has made a full recovery. He dotes on her children. Can little Kurt walk yet, he wonders?

In early June Wommer writes that he is now an ‘aspiring’ officer. Further training would assess if he was really suitable. Promotion from the ranks to become a commissioned officer was quite rare in the German Army. Wommer has done well for himself. He writes of the need for patience, hope and courage, or as St Paul put it ’faith, love and hope’. He prays for an end to all this misery and privation. He can hear the British bombardment from around the town of Ypres. It has been going on for several days. That same day tunnels dug deep below the German trenches and packed with high explosives had been detonated. At the time it was the largest man-made series of explosions. Then there was the thud of the creeping barrage as the British infantry cautiously advanced over no-man’s land.

In November Wommer found himself posted to part of the newly constructed Hindenburg defensive line near Cambrai in northern France. A major British offensive had been planned using the newly-developed tanks. They had been in use for just over a year with mixed results. With a top speed of around 3 mph in ideal conditions, these lumbering monsters could crush the barbed wire and provide vital cover for the accompanying infantrymen. Wommer had by now been promoted to 2nd Lieutenant. Attached to a machine-gun company his unit would have been one of the main targets of any enemy advance. Wommer’s regiment was attacked by a Highland Division which still went into battle wearing suitably camouflaged kilts. More Skipton prisoners were captured on this one day, 20 November 1917, than any other day of the war. And after 84th Infantry Regiment over to the right, more prisoners were taken from Wommer’s unit than from any other regiment. A few hundred yards away four battalions of the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment including Territorials from in and about Skipton completed a record advance of four and a half miles in one day.

Jakob Wommer was captured on the morning of first day of the battle, and would arrive in Skipton two months later in the third batch of German officer prisoners. Sadly, he would never see his homeland again, as will be revealed in the next article…

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here