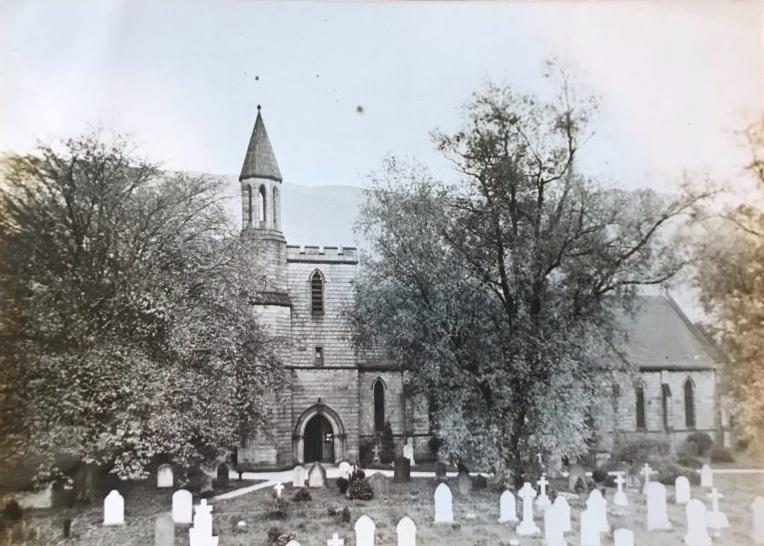

THE Settle Graveyard Project documents the lives of those buried at Holy Ascension Church since 1839, and its far from over, writes John Cuthbert.

THE Settle Graveyard Project documents the lives of those buried since 1839 in the graveyard at Holy Ascension Church, Settle. The project is being carried out by a team of volunteers led by Sarah Lister.

When people research their family history they sometimes come across a graveyard and decide to catalogue the gravestones they find there.

You would be forgiven for thinking the Settle Graveyard Project might be just another one of those lists, but it isn’t. It is so, so much more.

Sarah Lister and her team do not just record the names of those buried within the graveyard at Holy Ascension Church, they research and write about their lives within Settle and the surrounding area.

So, rather than a simple list of names, this is a series of stories showing what life - and death- was like in Settle from the 1830s onwards.

This is part of an entry for ‘Honest John Patrick’ and his ‘dishonest’ relations.

John Patrick was one of eight children of Charles Patrick, an agricultural labourer and his wife Sarah Taylor, who came to North Craven to settle.

The family lived in Banham, east of Thetford, Norfolk which is now known for its pretty thatched cottages and a zoo.

When he was 18, on October 3 1869, John married Elizabeth Matilda Cracknell who was born soon after her father, James Cracknell, died.

Elizabeth Matilda’s mother Mary (Farrow) Patrick brought up nine children single handedly - no easy task.

Daughter Elizabeth Matilda, although only 17, gave birth to a son, Robert John Cracknell, just two months before her marriage to John Patrick. John and Elizabeth went on to have six daughters, moving to Settle in time for the birth of daughter number four, Mary Elizabeth.

East Anglia suffered from an ‘agricultural depression’ during the second half of the 19th century as new machinery was removing the need for agricultural labourers.

As a result, thousands of East Anglians left to find work in the cities and hundreds came to Settle for work in the mills, on the new railway or limestone quarries. They formed communities wherever they settled - surrounded by strange accents!

John worked as a quarrier in the limeworks but later took up gardening.

Diarist Charles Green reported: “I remember working for Mrs Henley of Hillside on Constitution Hill, and a dear old lady was she.

“I attended to the flowers and pruning etc and Mr Jack Patrick was Mrs Henley’s kitchen gardener and handy man.

“Jack Patrick was known to most folk in Settle, a typical Norfolk man is Jack Patrick, ways of his own, which are not amiss when understood. Honest John Patrick would be a good name for him’. Widow Mrs Henley moved to Settle after her husband Thomas Clark Henley, the vicar of Kirkby Malham, died in 1897.”

Another subject of Sarah Lister and her team is the Moore family.

“The Moores, with an exceptionally talented nurse: Robert, born in September 1860 near Hawes, was the illegitimate son of Agnes Moore, a farmer’s daughter.

Robert was born just two months before Agnes married John Thwaite Metcalfe and they had another seven children. Despite living with Agnes and John, Robert was referred to as ‘grandson’ in the 1861 census which probably suggests he was not John’s son.

When he was 19, in November 1879, Robert married 18-year-old farmer’s daughter Ann Sunter.

They were both working as servants at the time. They remained in Hawes with Robert working as an agricultural labourer while Ann started on the production of seven daughters.

Four of them, the eldest Agnes and the youngest three, Isobel, Rose and Esther died in infancy. Such was Victorian England.”

These are just two of over 200 stories of lives in Settle. There are honourable people in these stories, plus some scoundrels. Sarah and her team continue with their research, so the collection is always growing.

This excellent archive is one of many within the ‘Capturing the Past’ project – collecting historical images, documents and words from those living in the Yorkshire Dales National Park.

The site is specially designed for displaying collections, but also accepts one-off contributions.

People use Capturing the Past when they have invaluable, historical material they’d like to share, but don’t have the resources to show it to the rest of the world. Capturing the Past was set up by the environmental campaigning charity, Friends of the Dales, for people and groups from across the Dales to catalogue and digitise their own local history archives.

To view the archives or find out more about adding yours, visit: www.dalescommunityarchives.org.uk; or if you’d rather just have a conversation about contributing something, email: dalescommunityarchives@gmail.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here