THIS is the first of a three-part story by University of Leeds Lecturer Anne Buckley on the life of Herbert Straehler, a German naval officer. Straehler had escaped from a Japanese PoW camp in 1915 and almost circumnavigated the world before being recaptured and ending up in Raikeswood Camp, Skipton, in 1918-19

IT is incredibly exciting that we now have two first-hand accounts of what is possibly the greatest untold escape story of the First World War. The diaries came to light last Easter when I travelled to Berlin to meet the family of Herbert Straehler, one of the Skipton prisoners from the First World War, and to attend the 94th birthday party of Straehler’s daughter, Liselotte Fedtke. For a year or so before this trip I had been in contact with Liselotte’s daughter, Uta Heidtke, who now lives in New Zealand and who was visiting her mother for the first time since the start of the pandemic.’

Uta said she found the diaries when I was helping my mum tidy her cupboards. I can’t believe they have survived so many house moves!’

Straehler’s accomplice in the escape attempt was Fritz Sachsse, who became the senior German officer at Raikeswood camp and who, along with Willy Cossmann, compiled the book ‘Kriegsgefangen in Skipton

Herbert Straehler was born in 1887 in Breslau (now Wrocław and now in Poland). His family then moved to Berlin, where he attended school. In 1906, he joined the Imperial German Navy as an officer cadet: on his CV he gives the reasons for his career choice as ‘an interest in the wider world and in technology’. His first journey took him to the West Indies, Mexico and Central America. In 1912, Straehler was sent to Hankou in China (now part of Wuhan City) as commander of a detachment assigned to protect Germany’s small piece of territory there during the Chinese revolution. He was given an award by the President of China and made an honorary Captain in the Chinese Army for protecting the local Chinese population.

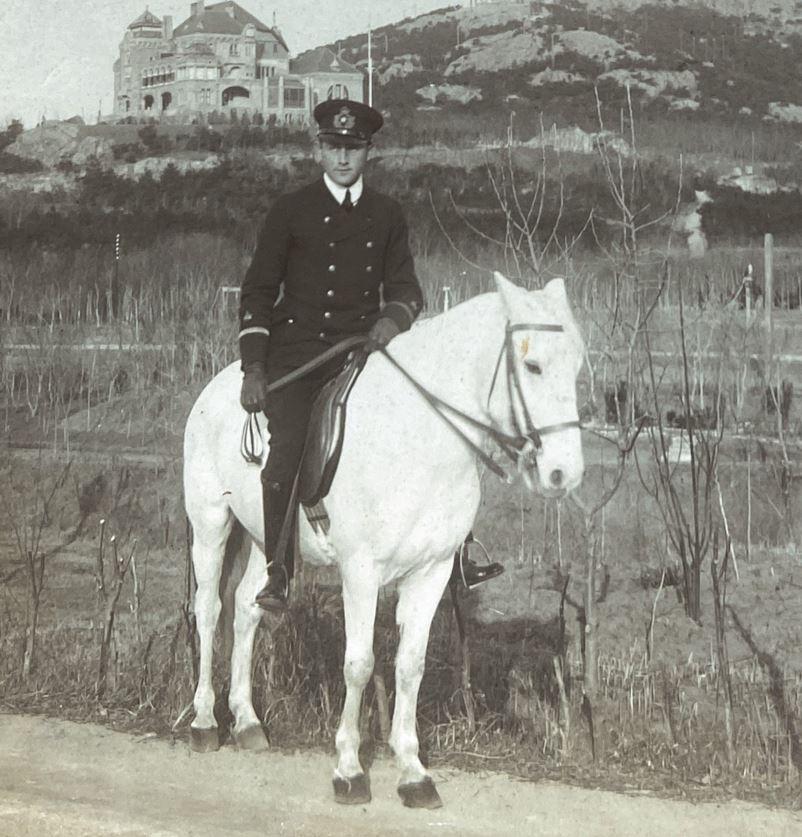

Straehler was then sent to the German concession of Kiautschou Bay (also in China) with its port city of Tsingtao. The German colonialists had built a European-style city with luxurious villas for the higher-ranking military and civilian personnel. They created a pleasant life for themselves in Tsingtao, Germany’s ‘place in the sun’. There were churches, a modern hospital, a horse racing course and beer gardens. The Tsingtao Brewery founded by the Germans in 1903 is still in operation and its beer is China’s most widely exported beer. The German architecture is well preserved and has become a tourist attraction.

Following the outbreak of the First World War, Britain turned to Japan for assistance in forcing Germany to hand over Kiautschou Bay including the Tsingtao naval base. Japanese troops, supported by British units, forced the German garrison to surrender in November 1914 following a two-month siege. Almost 5000 Germans were taken prisoner by the Japanese and transported to various camps in Japan.

Straehler was one of these prisoners and he was taken to the Fukuoka camp in southern Japan. On arrival he was handed over to a Japanese officer, Lieutenant Suzuki, who greeted him with the words: ‘My invitation to you to come to Japan was not intended to be like this’. It turned out that Lieutenant Suzuki was one of the Japanese officers who Straehler had shown around Tsingtao at the beginning of 1914.

Another Fukuoka prisoner who would also end up in Skipton was Fritz Sachsse. His diary provides more details about the journey to Japan and a description of the camp: “The crossing to Japan was fairly comfortable. After 2.5 days we arrived on the southernmost island of the Japanese mainland. During the rail journey of several hours to our destination of Fukuoka, we were attended to by Japanese ladies who brought us breakfast in dainty baskets. When we arrived in Fukuoka there were crowds of thousands of people at the station and in the streets but they didn’t get to see much of us as we were immediately taken by the Siemens electric tram to the officers’ camp. The camp consisted of a number of large and small buildings situated directly on one of the many bays on the western side of the island of Kyushu, very close to the city of Fukuoka. Our camp did not offer much space for movement but we were able to perform physical activities on a small sports pitch, some garden areas around the buildings, and an 80-100-m long promenade along the water. From the promenade we had a wonderful view across the bay to the islands and islets.”

On 13 November 1915, after a year in captivity, a fellow officer, Captain Kempe, escaped from the Fukuoka camp. Straehler volunteered to impersonate him when the Japanese came round to hand out the imprisoned officers’ salaries. He lay in Kempe’s bed with a bandage around his head pretending to be ill. He signed for Kempe’s money before jumping out of a window and joining his comrades on the parade ground, where he received his own salary. Straehler was then forced to escape himself to avoid being charged with assisting Kempe. A day later Sachsse also made his escape.

Next week the story continues with diary extracts from Sachsse and Straehler’s journey through Japan and Korea and then across China.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel