EDWARD Ayrton was a scholar at a grammar school in Horton-in Ribblesdale in the mid 1800s. His school books show how different his learning was compared to modern-day teenagers. No computers for him, learning about the world involved the laborious copying out of maps. Here, John Cuthbert of 'Capturing the Past' gives us a glimpse into what Edward would have learnt.

WHEN we look back at our days at school, we have a variety of reactions. Some remember it fondly, recalling days of friendship and learning. Some have the opposite reaction, remembering cold classrooms, fierce and uncompromising teachers and incomprehensible subjects.

‘Capturing the Past’ gives an opportunity to look back at the school days of the mid-19th century, showing exercise and copy books of a pupil in the Dales. It shows how his future life was being influenced by his schooling and the kinds of subject matter considered important for a grammar school pupil some 164 years ago.

Edward Ayrton attended a grammar school in the mid-19th century. The school, in Brackenbottom Lane, Horton-in-Ribblesdale, was founded in the early 16th century as a free grammar school and converted to a grant-maintained C of E elementary school in 1878. The young Edward attended the school from 1859 to 1864.

Although grammar schools were originally created to allow pupils to learn the classical languages of Latin and Greek, Edward’s education prepared him for a more practical career.

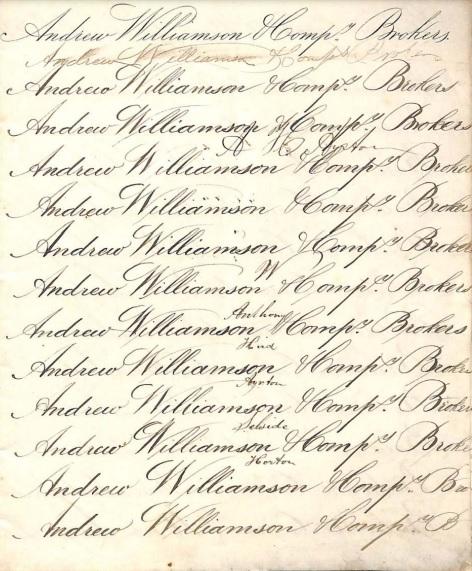

His exercise books show how he copied standard phrases to improve his handwriting, how he copied maps to learn about the world, and how he did calculations to prepare him for trade. Edward’s exercise and copy books are dated from 1859 to 1864. We do not know his exact age, but traditionally, grammar school education finished at the age of 14.

Edward’s 'copy book' does not contain modern phrases such as ‘How much would I save in postage if I joined Amazon Prime?’ or ‘How to connect a wireless printer to a tablet over wi-fi’. The handwriting practice he was undertaking used phrases such as ‘Andrew Williamson & Company Brokers’, ‘Commission upon this Month’s Sales £390’ and ‘Edmundson & Underwood. Haberdashers’. Copying such text not only perfected his handwriting, it also shows us the kind of subject matter considered important at the time.

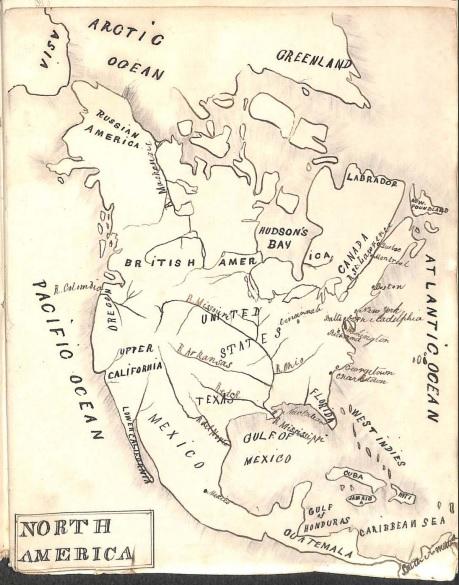

Edward had to copy maps into one of his exercise books. He had copied maps of South America, Europe, Asia, North America, Spain and Portugal, the British Isles and one of France.

If readers look at modern maps of these parts of the world, they will see a number of differences: ‘Arabia’, ‘Hindoostn’ (sic) and ‘Siam’ were marked on his map of Asia.

We would now write ‘Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, UAE and Oman’, ‘Pakistan, India and Bangladesh’ and ‘Thailand’. ‘British America’ and ‘Russian America’ are marked on his map of North America. We would now mark them as ‘Canada’ and ‘Alaska’. ‘Greenland’ is rather vague in its outline and was not shown as an island.

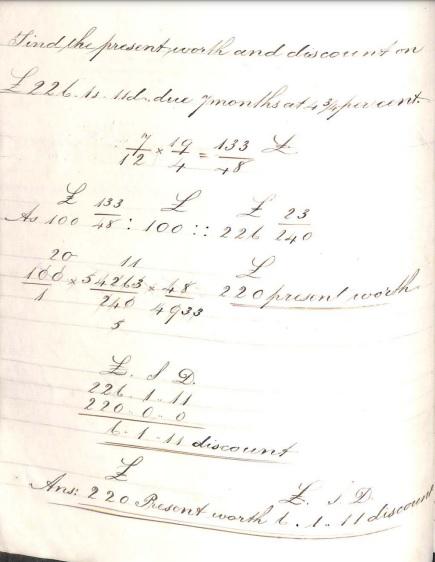

Edward had to learn how to work out his sums – no calculators here. The kind of life he was being prepared for is shown in the type of problems he had to solve: ‘At an election where 979 votes were given, the successful candidate had a majority of 47; what were the numbers for each?’ and ‘What is the discount on £257, 8s, 8¼d paid 210 days before due at 4½ per cent?’.

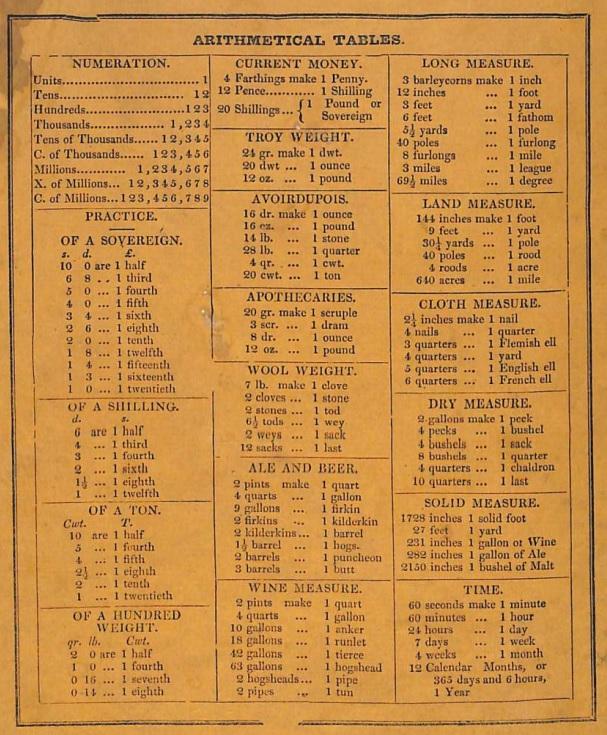

For those readers old enough to remember ‘pounds, shillings and pence’ this last problem may sound familiar. Problems in every-day arithmetic were complicated by having subdivisions of different sizes.

For example, one pound was 20 shillings; one shilling - 12 pence. Weights were even more complicated: one ton was 20 hundredweight; one hundredweight was four quarters; one quarter was two stones; one stone was 14 pounds; and one pound was 16 ounces.

Anyone trading with companies overseas had to cope with even more units. For example, when measuring cloth: 2¼ inches made a nail; four nails made one quarter; three quarters made a Flemish ell, four quarters made a yard, five quarters made a British ell and six quarters made a French ell. Let us hope that Edward remembered all these things as he moved forward into his adult life.

This excellent glimpse into our history is one of many within the ‘Capturing the Past’ project. We collect historical images, documents and words from those who lived or are living in the Yorkshire Dales National Park.

Capturing the Past is managed by Friends of the Dales and was developed by the Ingleborough Dales Landscape Partnership, led by YDMT and supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. To view the archives or find out more about adding yours, visit: www.dalescommunityarchives.org.uk If you’d rather just have a conversation about contributing something, send John Cuthbert an email: dalescommunityarchives@gmail.com Edward Ayrton’s school books can be found at: dalescommunityarchives.org.uk. Once you are on the home page, type ‘Edward Ayrton’ into the search box.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here