A RECENT event in Barnoldswick celebrated 80 years of Rolls-Royce engines in the town. Historian Alan Roberts looks back to the early days of the jet engine and how it all started.

FRANK Whittle was not only a daring pilot, but also an extremely talented engineer and inventor who had patented his ideas for a jet engine as early as 1930.

The RAF did not see much future in Whittle’s design at the time so he set up his own company ‘Power Jets’. The advent of the Second World War stimulated renewed interest in Whittle’s design for a new kind of engine for an extremely fast fighter plane. Whittle’s firm was deemed too small for the development and production of this engine on its own.

It was agreed that the Rover Car Company would carry out this work with Whittle still responsible for the design and other technical matters. It was based in Bankfield Shed, a disused cotton mill in Barnoldswick. Difficulties soon began to arise. Rover could not provide components to the required standard and progress became very slow.

Eventually a deal was thrashed out in the ‘Swan and Royal’ hotel, in Clitheroe, between Ernest Hives, the chairman of Rolls-Royce and Spencer Wilks his opposite number at Rover: Rolls-Royce would take over the jet engine project at Barnoldswick and in return Rover would receive Rolls-Royce’s tank engine manufacturing plant in Nottingham.

The aim was to get a reliable jet engine in service as quickly as possible. The first engines were delivered late in 1943 to power the twin-engined Gloster ‘Meteor’ fighter. The engine (the W.2B/23) was later to be called the Rolls-Royce ‘Welland’.

An early success was when a ‘Meteor’ caught and destroyed a German V-1 flying bomb in August 1944. Unfortunately, Nazi Germany had already introduced its own jet fighter, the Messerschmitt Me 262, a few months earlier. It was potentially a very effective weapon due to its extremely high speed, but a shortage of raw materials to make high-temperature steel alloys and an excessively high fuel consumption limited its availability.

Nevertheless, Barnoldswick can rightly claim to be the cradle of the jet engine. It was, after all, here in Barlick that Frank Whittle’s vision of the jet engine finally became a reality.

Barnoldswick History Society has begun the work of cataloguing its own quite extensive archive. Further insights into life in our town during the 1940s have recently been uncovered.

The drill hall, home to the Barnoldswick Company of the 1/6th Battalion of the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, was closing. Cyril Dinsdale, the steward of the attached Territorial Club, would be out of work. The officers rallied to support him. Major Whittaker wrote that Dinsdale was ‘a man of temperate habits, clean, prompt and absolutely honest’. It was 1940 and Britain was again at war with Germany.

In January, Cyril became a constable with the Admiralty Civil Police and spent three years in Portsmouth. He then returned to Barnoldswick to His Majesty’s Victualling Depot at Long Ing, a surprisingly long way away from the sea! Peace came, and after short stints at the Royal Navy stores at Wellhouse Mill and an Admiralty Signals Establishment in Keighley, Cyril was no longer needed by the police.

A commemorative stone from the drill hall has been laid next to Barnoldswick’s war memorial near the Co-op car park. The memorial reminds us that more than seventy servicemen from the area lost their lives in the Second World War.

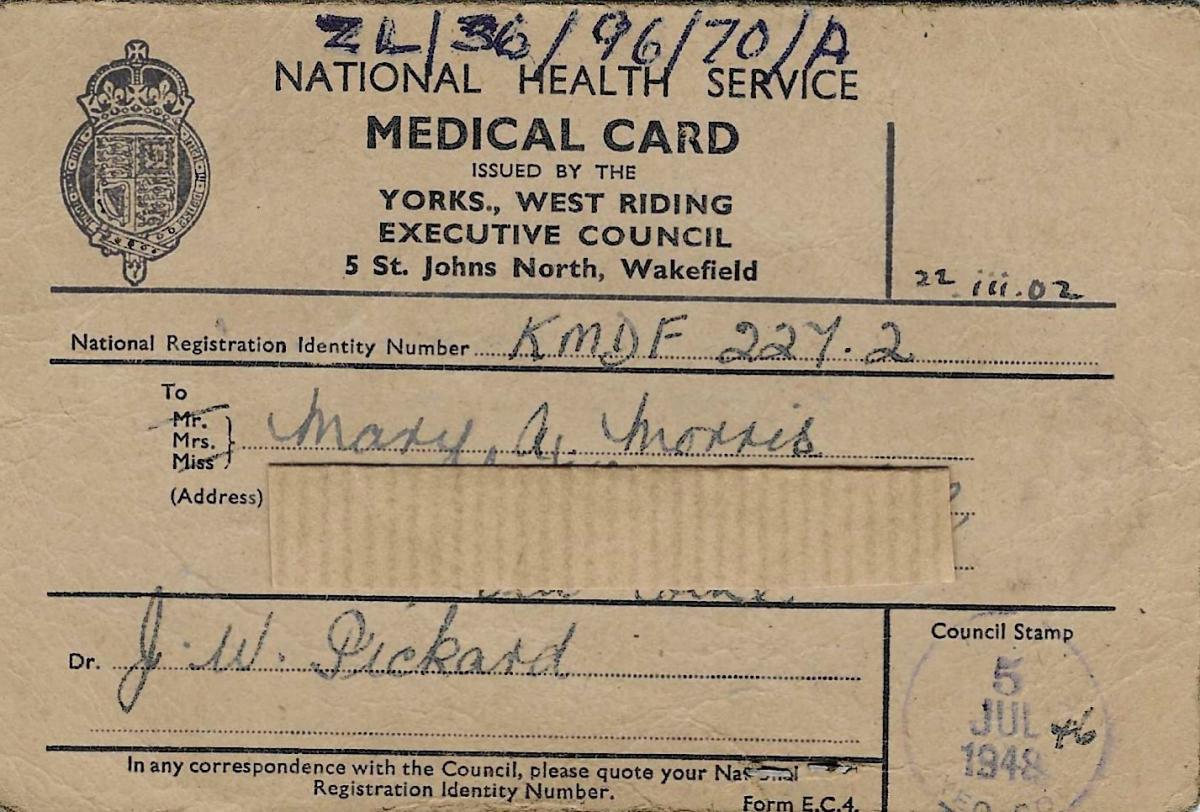

Civil liberties were restricted in wartime Britain. Everyone had to carry an identity card at all times: there might be spies everywhere. Young Mary Morris also had to have a travel card, issued by the Passport Office in Liverpool, to travel to either Northern Ireland or to Eire.

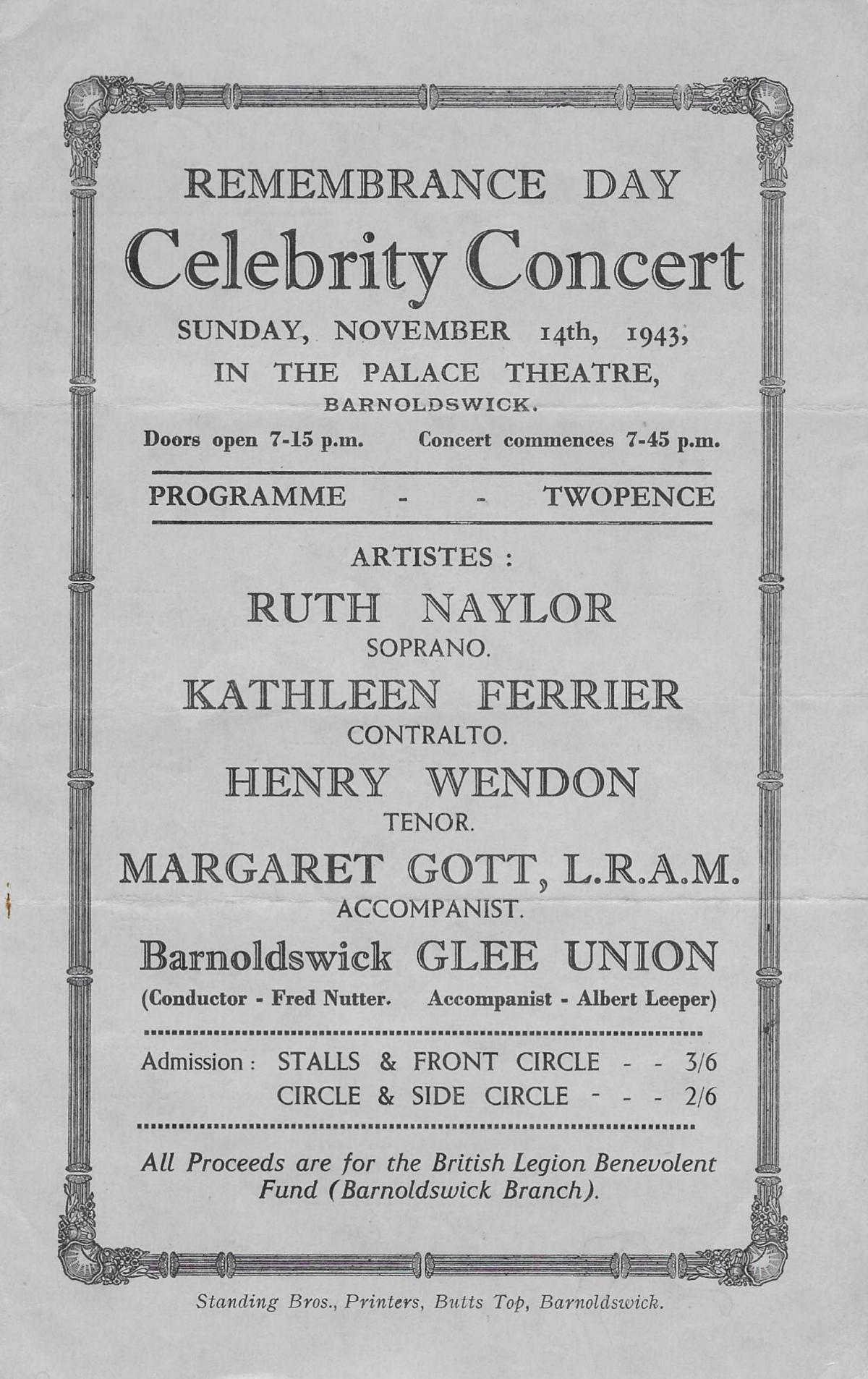

The Remembrance Day concert at the Palace Theatre in 1943 featured a young contralto called Kathleen Ferrier. She had been born at Higher Walton near Preston. Even as a young girl it was clear that she had a rich and powerful voice. At school in Blackburn, she was told to stand at the back of the choir and sing quietly.

She made her first radio broadcast as a singer in 1939 and excelled in a performance of Handel’s ‘Messiah’ at Westminster Abbey in 1943. Six months later she was in Barnoldswick. She sang two songs plus ‘It is in the merry month of May’ as a duet; the evening finished with a stirring performance of ‘Abide with me’ by the Barnoldswick Glee Union. It was no accident that Kathleen was in Barnoldswick. She had been engaged to provide music throughout the country in church halls, cinemas, schools, indeed wherever an audience could be found. This was wartime and morale had to be maintained!

Kathleen would later perform in many different countries, but her glittering career was brought to an end by cancer. She died in 1953, aged just 41.

And finally, we return to Mary Morris. The war had been won and the National Health Service was launched with free medical care for all. That was seventy-five years ago and Mary made sure she had that exact starting date ‘July 5, 1948’ stamped on her NHS medical card.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here