Robin Longbottom examines how the arrival of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal brought prosperity to a quiet village

HIGH on Farnhill Moor, on the village’s northern boundary, is a large rock called the Parting Stone.

It is significant because it's one of only two surviving boundary stones marked with the letter ‘B’ for Benson.

Robert Benson was born in Wrenthorpe, near Wakefield.

He had studied law and following the restoration of the monarchy after the English Civil War he was appointed clerk to the Assize Court in Yorkshire. He was a shrewd and unscrupulous businessman and between 1660 and his death in 1676 he took advantage of his position to buy the estates of gentry who had fallen into debt after the civil war. He acquired several manors including Bramham near Leeds, Bingley, Elslack and Farnhill.

Benson’s only son, Robert Benson junior, inherited the estates and entered Parliament in 1703. In 1711 he became Chancellor of the Exchequer and on his retirement in 1713 he was raised to the peerage and made Lord Bingley. He built himself a grand house at Bramham Park and died in 1731, leaving one daughter, who married George Fox. His estates, including Farnhill, then passed into the hands of the Lane Fox family.

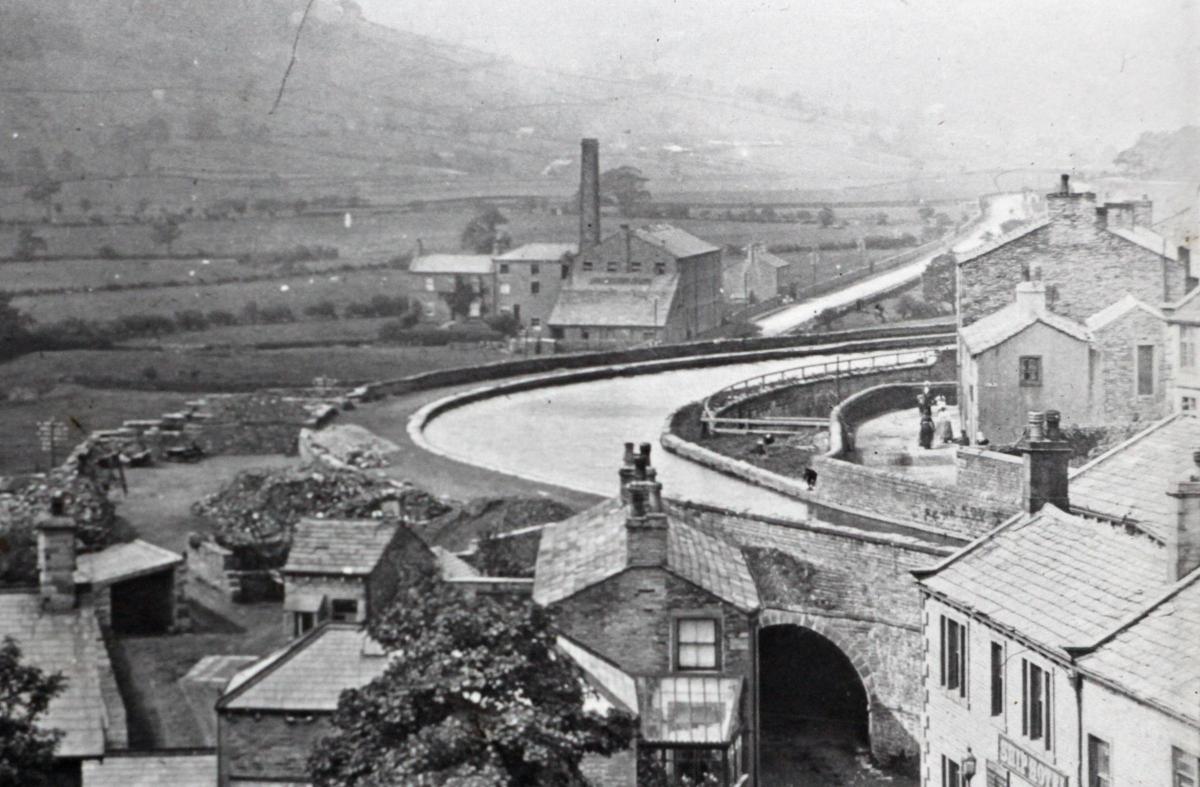

Other than draw rents from the village the lords of the manor appear to have done little, if anything, to improve it and Farnhill remained a sleepy backwater until the Bingley to Skipton section of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal opened in 1774. The canal passed through the village and brought with it commerce and opportunity. Warehouses, a malt kiln and a cotton mill were built alongside it and the canal company employed an agent nearby in Kildwick. A lime kiln was built into the canal embankment to burn lime to cater for the demand for mortar, for the construction of local mills and housing. In 1829 it was the scene of a tragic accident. Robert Hergeson, an ostler at the White Bear Inn, Cross Hills, was returning from Skipton late one night. Instead of coming along the turnpike road he rode back along the canal towpath, probably to avoid paying a toll. Unfortunately, as he approached Farnhill, his horse veered off the path and both fell into the kiln. He was found dead the next day and the horse had to be destroyed.

In 1823 the malt kiln closed, and was put up for sale and converted into a textile mill. The village now had two textile mills and needed more housing to accommodate the mill hands. Many older houses were replaced and a new row, called Middleton, was built by the Farnhill Order of Odd Fellows to provide dwellings for its members. These properties were often known as club houses as they were built using funds raised by self-help societies, the forerunners of today’s building societies.

By 1875 a third mill, Airedale Mill, had been built on land alongside the turnpike road to Skipton. There were now three mills in Farnhill. The old malt kiln, which had been extended, was in the hands of Aked Brothers, worsted spinners, and the former four-storey cotton mill was occupied by Messrs Green, worsted spinners, and Thomas Dennison, a worsted manufacturer. Airedale Mill was also spinning worsted yarn and had two occupiers, Samuel Watson and J Stephenson & Co. The village also had a small tanning industry with tan pits and sheds on land between the canal and Skipton Road.

With regard to amenities there was one public house, the Ship Inn, a methodist church and the Odd Fellows meeting room in Middleton Row. Children from the village attended the church school nearby in Kildwick.

Today the prosperity that the canal brought to the village is now long gone and the mills alongside it have been converted to dwellings. Airedale Mill burned down in 1905 and the tannery had closed by 1900.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here