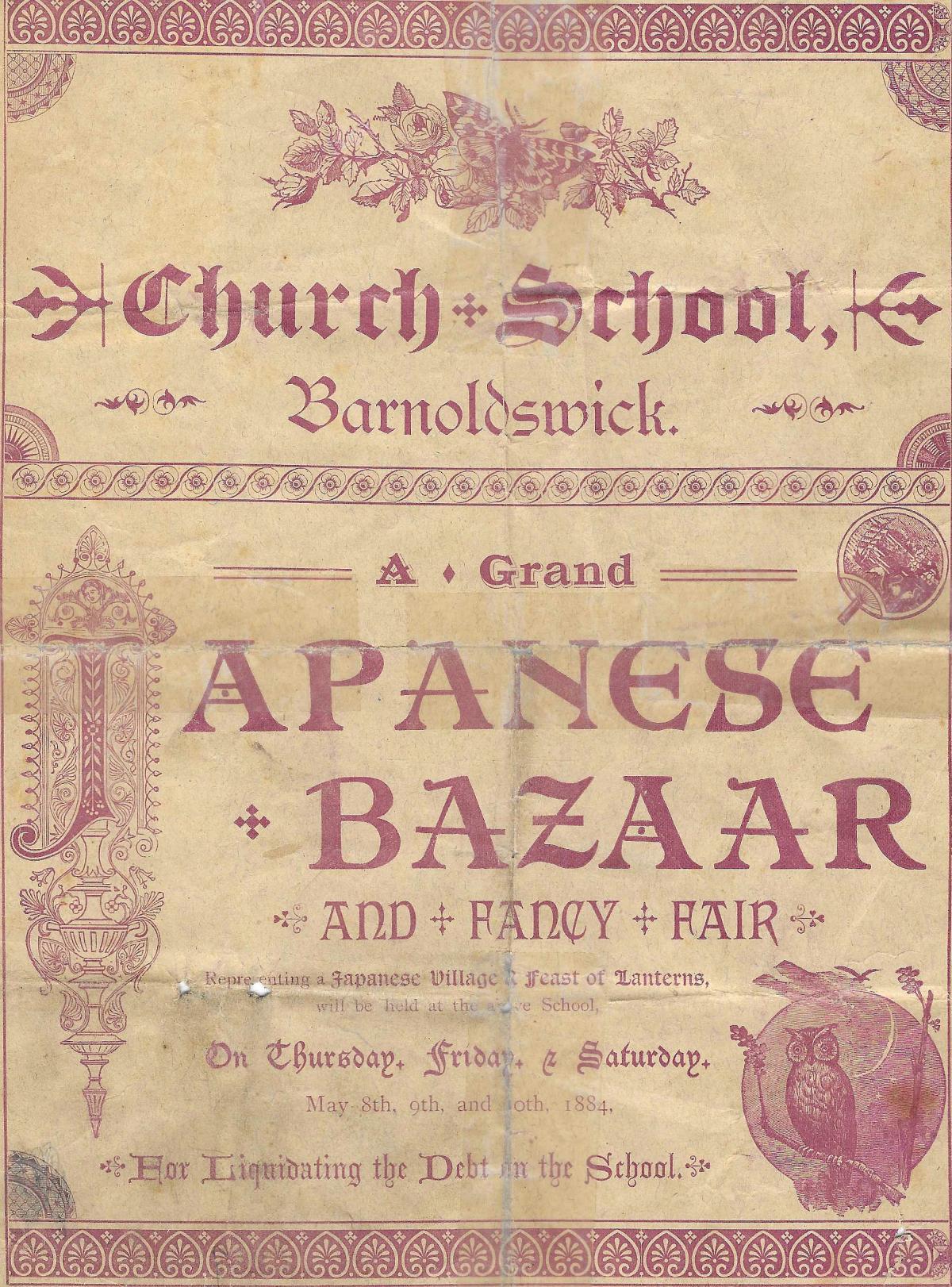

A Japanese Bazaar! What could be more exciting? It was 1884, and a late train had been provided to leave Barnoldswick at 8.15 each evening. Cheap return tickets would be issued at Colne and Skipton throughout the three days of the bazaar......writes historian Alan Roberts.

PEOPLE would surely come in droves and for such a good cause. Church School, or more formally Barnoldswick Church of England School, had been built the previous year for £1,800, yet there was a huge debt to clear.

The Japanese bazaar and ‘fancy fair’ was held in the school in York Street. Inside the school a Japanese village would be created together with a feast of lanterns. It was opened by Mrs Roundell, of Gledstone Hall, supported by Mr Roundell the local MP (if parliamentary business allowed). This was a high-profile occasion: the patrons included Countess Bective, Lord and Lady Ribblesdale, the dowager Lady Ribblesdale and a couple of bishops. A list of patrons worthy of Downton Abbey, but firmly set in West Craven.

Admission was not cheap. On the opening Thursday it was two shillings reducing to just sixpence on the Saturday. What about a season ticket at just half a crown, or make an occasion of it with a meat tea at one shilling, or even luncheon on the opening day for two shillings?

But what did you get for your money? The various stalls represented Japanese cottages, temples and pagodas with names like ‘The Golden Gate’, ‘The Celestial Moon’ and ‘The Land of Delight’. The entire circuit of the rooms was hung with 3000 feet of canvas where ‘artistic skill’ was used to recreate Dia Nipon, the ‘Land of the Rising Sun’. Japan’s ‘long and proud isolation’, we were told, ‘and recent renewal of relations with inter-civilisation… have created deep interest in England’.

Not everything was Japan-themed. There was a colossal moving panorama of Egypt and the Holy Land with ‘gorgeous moving processions’ and dioramic effects interspersed with music. That was threepence. Then there was the Living Mummy: a ‘statue of flesh’ and ‘immortal of the dead’ which was another twopence.

For a penny more you could visit the Cave of the Hermit and see a living man beheaded, or what about the marionette exhibition or the automaton ‘Jumbo’? The Edo Restaurant offered pork pies, beef sandwiches and currant buns. Then there was the fairy well, the microscopes and a galvanic battery. There was something in the bazaar for everyone. You could even sing ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ after Mrs Roundell’s opening address. No wonder there was an evening train. There was a nugget of truth behind all the showmanship and razzamatazz.

Japan had effectively isolated itself from the rest of the world for over two hundred years. No one was allowed to enter or leave the country on pain of death. The exceptions were two small ports where Dutch and Chinese merchants were permitted to conduct a limited amount of trade. The Japanese had originally welcomed western visitors and their technology. The authorities soon realised that one likely result of Portuguese missionary work would be a foreign takeover of their own country. The shogun therefore took the extreme step of expelling the missionaries and banning the Christian religion.

One effect of isolation was the blossoming of Japanese art and culture including bonsai trees, haiku poetry, wood-block printing and the traditional tea ceremony. However, during the years of isolation, Japan had fallen well behind the rest of the world. In 1853 four American warships steamed into Tokyo Bay and demanded the right to trade with Japan. The military and industrial might of the modern world was confronting a seriously underdeveloped country. Japan had no choice but to comply. Its breakneck campaign to catch up would only lead to tragedy, but that is another story.

Elsewhere dramatist WS Gilbert and composer Arthur Sullivan had hit upon a winning formula by writing a series of comic operas. In 1884 they were facing a crisis. Sullivan wanted to spend more time on his other work as a composer, and was unimpressed by Gilbert’s ideas for future collaborations. Would the partnership split up before it had realised its true potential, or would Gilbert finally come up with the goods? Gilbert’s solution was to write an opera set in Japan, which also provided ample opportunity to lampoon our British institutions and our own way of life. The opera was ‘The Mikado’. The lure of a hitherto forbidden country proved irresistible. A craze for all things Japanese had continued unabated in Britain.

Almost fifty years later ‘The Mikado’ came to West Craven. Barnoldswick Choral Society produced one major show each year. Beginning with a strict repertoire of Gibert and Sullivan, it later progressed to perform its own productions of popular musicals. It must have been great fun to take part: the camera, they say, never lies.

Thanks are due to Barnoldswick History Society for use of its own extensive archives Meetings are held in the Pensioners Centre in Frank Street each month. The next talk is by Jenny Hill on Thursday 28 September and is called ‘Behind the scenes at Craven Museum’

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here