Robin Longbottom recounts how dialect was once used extensively across South Craven villages

ON September 8, the Yorkshire Dialect Society began a six-week course at Keighley Library to introduce people to the vernacular of the area.

Fifty years ago, dialect could be heard regularly throughout the villages of South Craven, particularly amongst the older generation, but you seldom hear it today.

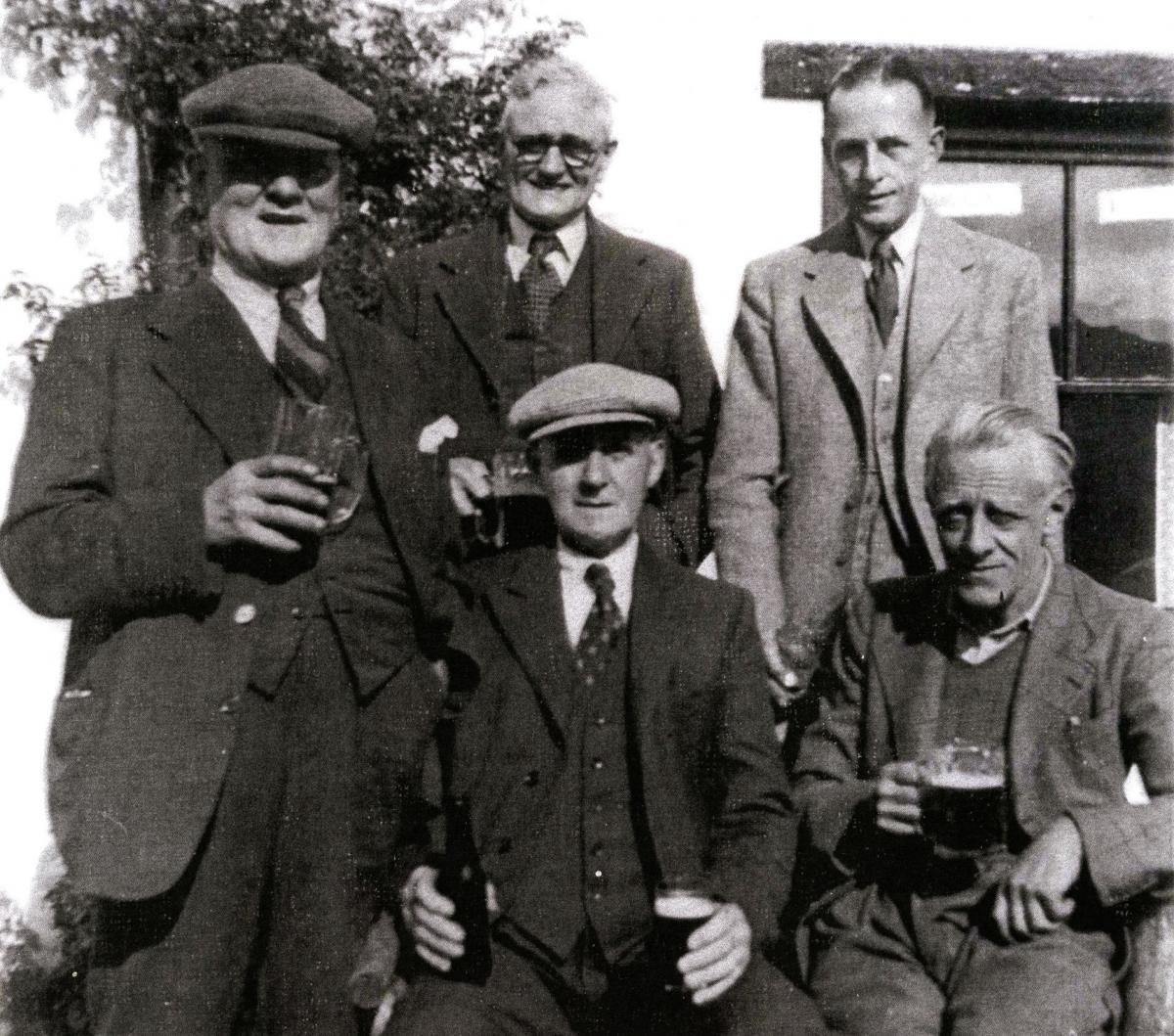

Pubs were often the best place to find dialect spoken as customers, often 'well oiled' after a pint or two, drifted back into the language of their youth. In tap rooms men sat round a table “ter cal” (talk), “laiked dominos” (played dominoes) and sometimes “got drukken as a wheel heead” (drunk as a wheel hub spinning around).

Joe Harry Haigh was the landlord of the Black Bull in Sutton-in-Craven until his death in 1983, and constantly used dialect words and phrases. If he ever heard bad news he would often respond, “aye, it’s flaysome living” (frightening living). If you were in his way when he was collecting glasses he would say, “ayup, lad! Ah nivver thowt thi muther bred a jibber” (a jibber was a horse that wouldn’t heck nor gee – go backwards or forwards). He always had a “ba’acan flitch” (side of bacon) hung up “in’t back ‘oyle” (back room) and if you were lucky he would cut you a “collop” (slice) or two for your breakfast.

Cedric Riley, who owned a baker’s shop in Cross Hills, was also a rich source of dialect. His grandparents farmed on Silsden Moor and his grandmother always called him “Cithric”, harking back to the Anglo-Saxon pronunciation of his name. He often told the tale of playing in a wet meadow and his grandmother shouting, “Cithric, come aht o’ t mow’n gerss tha’ll be witsherd” (Cedric, come out of the mown grass you’ll get your shoes wet – wet shod. Putting the ‘r’ after the vowel was common in Yorkshire dialect, so grass became gerss, great became gert and grin became girn). He often came out with almost unintelligible phrases, such as the time he asked one of the girls in the bakehouse to “tak claht aht o’t slopstone an’ put it in’t lowp ‘oyle” (take the cloth out of the sink and put it on the window ledge).

Many elderly people still used old past tenses such as “putten” and “gotten”. When a pupil is said to have written “putten” the teacher asked the class what was wrong with the sentence. A boy raised his hand and said, “please miss, he’s put putten when he should have putten put”. Lizzie Norton in Sutton used the now forgotten past tense “snew” if there had been a fall of snow and always repeated the word several times, “it snew and snew and snew”.

Nearly every small space or room was an “oyle” (hole) so you had a “coil oyle” for storing coal, a “wesh oyle” for washing in and a “muck oyle” generally full of rubbish. When a southerner is said to have asked “if you call a hole an oyle what do you call oil?” the response was “greease” (grease).

There was a host of greetings when two people met. “Nah, then” (now then) would generate a nod and “nah, then” back. “Ow’s ter doin” often resulted in the response “fair to middlin” (quite well) or comically “nay, ahm waar nah, than ah waar, when waar were on” (I’m worse now than I was when the war was on). When a lad came back after the war a villager said “Oh! Ah couldn’t own tha at furst, but I see it’s you, tha’s getten thi faather’s streeak and ’is jowills” (I didn’t recognise you, but I can see now you look like your father).

The last word must go to Joe Harry’s wife, Jean, “cahr quiet and od thi whisht” (quieten down and shut up).

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here