Earlier this month, one of our history features looked at the sinking of the hospital ship HMHS Rohilla off the coast near Whitby, which resulted in the death of 12 Barnoldswick men. This week, Lesley Tate looks at how the tragedy has been remembered over the years.

IN August this year on the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War, around 100 people gathered at the Church of St Mary-le-Gill, Barnoldswick.

They included the 100-year-old niece of two men who died when the hospital ship, the HMHS Rohilla, ran aground and sank off the coast of Whitby during one of the worst storms to ever hit the Yorkshire coast.

Winifred Fairchild's uncles, Thomas and Walter Horsfield, were among 12 Barnoldswick men to lose their lives on the ship on the night of October 30, 1914.

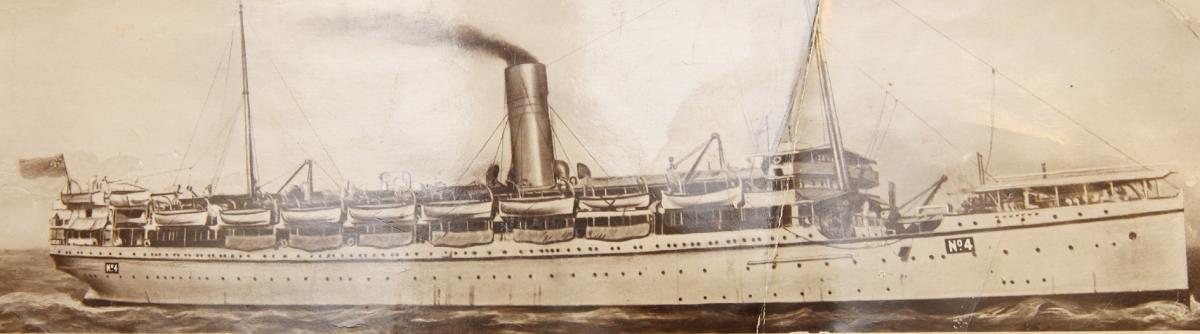

The steamer, which had been converted to a naval hospital ship at the outset of the war, was on her way to Dunkirk to bring back wounded soldiers. On route from the Firth of Forth, she hit submerged rocks and broke into two within half-a-mile of the coast. Over the next three days, some of those who attempted to swim to safety were rescued, although many were lost, and lifeboats were able to rescue others. In all, 146 of the 229 on board, survived.

A special anniversary organised by the Whitby Lifeboat Museum is to be held in the seaside town this weekend.

It will include an exhibition of Rohilla artefacts and memorabilia, a wreath-laying at the site of the wreck, the unveiling of a specially commissioned plaque on West Pier and a service of Remembrance at St Mary’s Church.

In many ways, it will mirror a commemoration held in Whitby 50 years ago on the exact date the ship went down.

In 1964, the commemoration was attended by two Barnoldswick survivors of the Rohilla - Anthony Waterworth and Fred Reddiough.

Mr Waterworth, who was then blind, had moved to Morecambe, but his colleague, who had made the event, despite having just been released from hospital, still lived in the town.

The Craven Herald reported the anniversary in great detail, via a 'special correspondent' and included pictures taken in Whitby of the gathering and the throwing of a wreath into the sea.

The Herald reported how the two men were scarcely apart for the whole day. "Linking arms, they were together at the Rohilla Memorial in Whitby Cemetery, high on the cliff top overlooking the sea; together in church, and together in memory as they relived those desperate hours on the stricken vessel knowing not whether they would live or die."

Mr Reddiough told the reporter he was "glad to be alive". "I might have died 50 years ago. I've just had a big operation and I'm lucky to be here today," he said.

Describing the events of October 30, 1914, the then chairman of Whitby Urban Council, Cllr Hubert Cummins, said it was a tragedy that had "burned itself on the hearts and minds of many".

The ceremony was also attended by two men who took to the sea in an effort to look for survivors. Brothers, Harry Richardson, 83, and John, 77, proudly wore their thick blue RNLI jumpers. The brothers recalled how one boat had become unseaworthy and how a second was lowered down a cliff - an operation that was at that time unique in lifeboat annals.

People travelled from all parts of the UK to attend the ceremony and it was thought that some relatives of every Barnoldswick man to perish in the disaster were present.

Norman Pickles, of Gisburn Road, Barnoldswick, whose father died, brought along the Rohilla wheel, which had been washed up on shore and given to him by a Whitby woman. There was also Hazel Rohilla Wilson, who had been born at the time of the disaster and who had been named after the ship in which her aunt's fiance died.

Around 120 people travelled from Barnoldswick to the ceremony, and all were received personally by the chairman of the council and treated to a three course meal in Whitby Spa. The British India Company donated £50 towards the cost and the event was supported by the Fishermen's Society, the RNLI, St John Ambulance, the British Legion and the Urban Council.

Following a ceremony at the Rohilla Memorial, there followed a service at the parish church. Around 1,000 people attended the service which included the singing of O God our help in ages past, and Eternal Father, strong to save. The Rector of Whitby told how the tragedy was an "unperishable" part of the history of the town and those who died on the ship were as much victims of war as those who had died on the Front Line.

The final ceremony was held out at sea where the Whitby lifeboat went to the exact spot where the Rohilla went down. It was surrounded by a small flotilla of boats, bearing civic heads and others, including those from Barnoldswick. On the cliff top, hundreds more gathered in respectful silence. Dozens of wreaths were thrown into the sea followed by the playing of the Last Post and Reveille.

The then chairman of the Royal British Legion told how he and his father had been first on the scene. He told how his father had spent three days trying to revive those washed up on the shore by forcing rum and whisky through their lips. Some survivors were brought home to his house. He said how all the hotels helped out in the town and how he had fitted out many of the survivors with shoes. His family had a number of candlesticks made from timber from the ship and also model lifeboats.

At the next meeting of Barnoldswick Urban Council, warm thanks were paid by the chairman, Cllr RW Hill, to the people of Whitby. He said the people of Barnoldswick would always be grateful to the people of Whitby for the kindness they had shown on the night of October 30, 1914. He added that whenever Whitby was mentioned in future, he would recall the reception he had received in the town, and how people had stood still in the streets as a mark of respect.

Cllr Hill also referred to a comment made by a member of the public that the commemoration had been nothing more than a 'spree' for a selected few. Cllr Hill said for perhaps the first time in his life, he had been deliberately rude to a member of the public in view of the spontaneous reaction of Barnoldswick and Whitby to the memory of those who lost their lives.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here