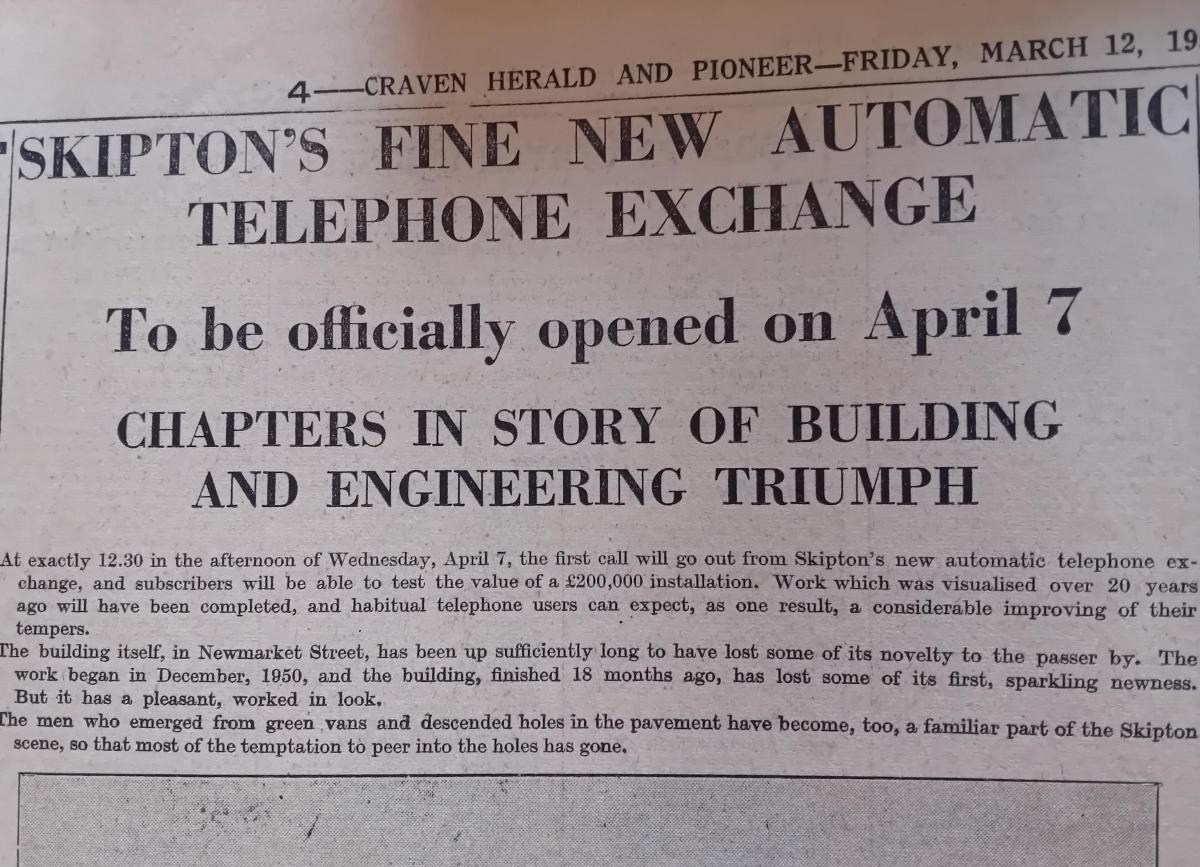

WITHIN a few weeks, on April 7, it will be the 70th anniversary of the opening of Skipton's 'fine new automatic telephone exchange'.

Described as an 'engineering triumph', the exchange, which replaced an earlier model introduced into the area in 1912, brought with it significant technological improvements, and connected numerous villages including Gargrave, Airton, and Malham.

The installation, was based in a modern building in Newmarket Street, which was built to purpose, and which cost £200,000 at the time (or more than £4.5m today), took place between 1950 and 1954.

The sight of the engineers at work constructing the exchange was such a novelty during this time that the Craven Herald of 1954 remarked on how residents suffered a ‘temptation to peer into the holes’ to see them at work.

For telephone subscribers, the new exchange brought numerous changes. Perhaps the one that seems most notable today is the introduction of 999 police emergency calls. This was somewhat behind the first implementation of the number, which was in 1937, within a limited area of London, but well ahead of the nationwide adoption, which was not to be completed until 1976.

Other outward changes enjoyed by those who used the service included the introduction of a higher pitched ringing tone, said to be ‘of great benefit to the subscriber’, and the option to dial 952, for the speaking clock. At the time this was delivered by Ethel Jane Cain, ‘the girl with the golden voice’.

The more significant aspects of the new technology were rather more behind the scenes. Though perhaps not appreciated by those outside the exchange itself, the retrofitting made the process of connecting and directing calls immediate and less labour intensive, allowing a larger audience to be better served.

This increased customer base came partly due to more comprehensive coverage of the area, with Airton, Arncliffe, Bolton Abbey, Burnsall, Cracoe, Gargrave, Grassington, Hellifield, Horton-in-Ribblesdale, Kettlewell, Long Preston, Malham, and Settle, all served by the new technology.

However, the expanded exchange was additionally planned to support the existing station in Leeds, relieving a level of pressure from the staff there with the new ‘trunk control centre.’

The new operators in Skipton - 16 day operators and seven night operators - were to enjoy ‘the best of working conditions’, with ‘a staff recreation room, dining room and kitchen.’ The new building, at 18 Newmarket Street, was decorated with a carefully planned system in which North-facing rooms were painted in warm colours, while Southern rooms were in pastels – ‘the latest idea in modern decoration.’ Supplementing this philosophy of interior design was ‘a mahogany floor and a view of the moors.’

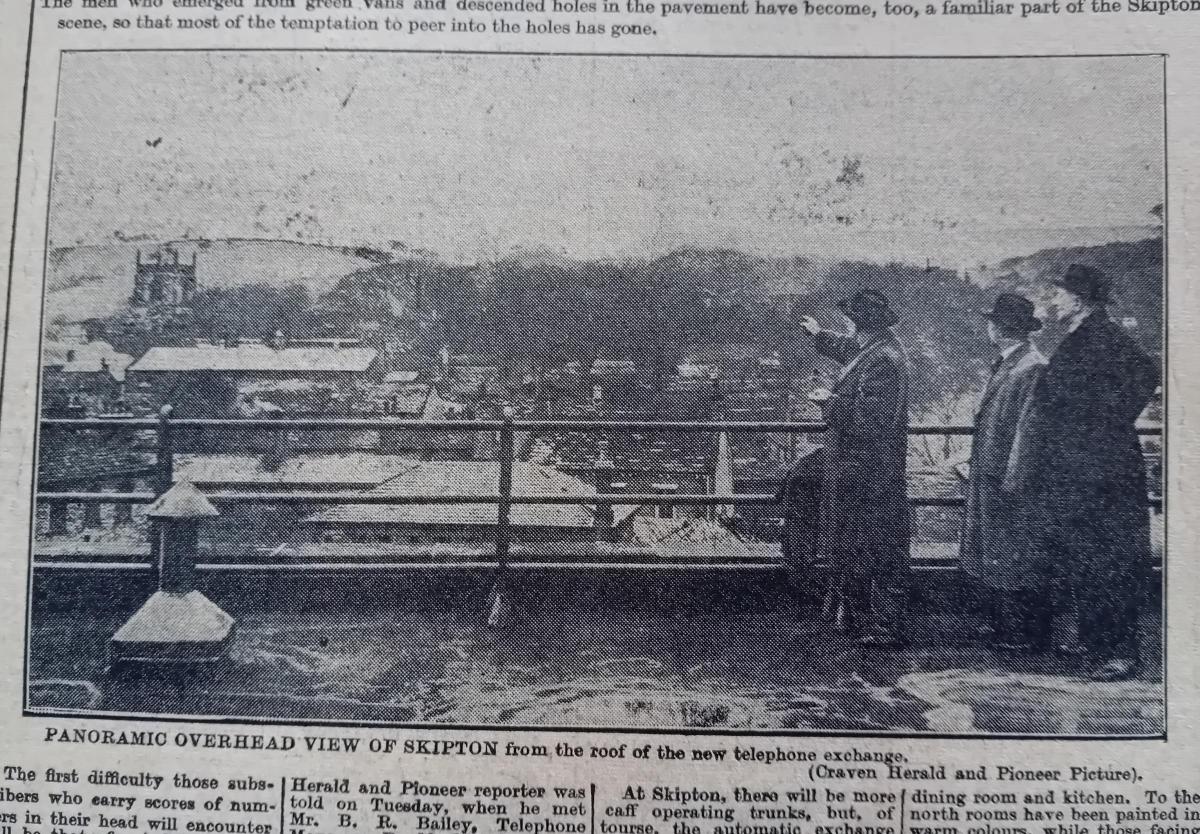

The building boasted - and presumably still does - a panoramic view of the surrounding area from its roof - the Craven Herald in celebrating its opening, included a picture of the gathered dignitaries admiring the view from the roof top.

As part of the installation, all existing telephones throughout the area were replaced or updated in order to remain compatible with the new technology. Telephone kiosks were retrofitted, and those who owned private phones had home visits from engineers, and dials fitted to their phones. In addition to these, new telephones were installed for those on a waiting list – which included a dizzying 84 people.

Unfortunately for those who received their new or improved telephones, all existing phone numbers were reset as part of the rollout, with a new directory of phone numbers issued in April of the same year. Readers were assured, however, that ‘as far as possible efforts have been made to make the new number similar to the old’, hopefully a relief to those who took pride in memorising these.

During the time of construction, the operation of national telephone infrastructure was handled by the Post Office, which dispatched ‘over 60’ engineers to oversee the implementation.

The Post Office would continue in this role until the early 1980s, when BT was introduced as a separate entity, and the telecommunications industry was privatised. In 1954, it was predicted that the town’s new automatic telephone exchange would bring benefit to the area for many years. The predicted lifespan for the technology was 30 years, after which the area ‘should be due for another type of exchange’. In fact, the pace of technology outstripped this, with a new automatic trunk dialling system introduced in 1961, which made it possible to make long distance calls without the aid of an operator.

Ultimately, Skipton was not to remain a hub of the telephone revolution. At the end of the predicted 30 years, in 1985, the telephone exchange was closed, as the introduction of digital systems meant that calls could instead be redirected through larger exchanges.

The building is still owned by British Telecom and the 'telephone exchange' sign can still be seen next to the front entrance.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel