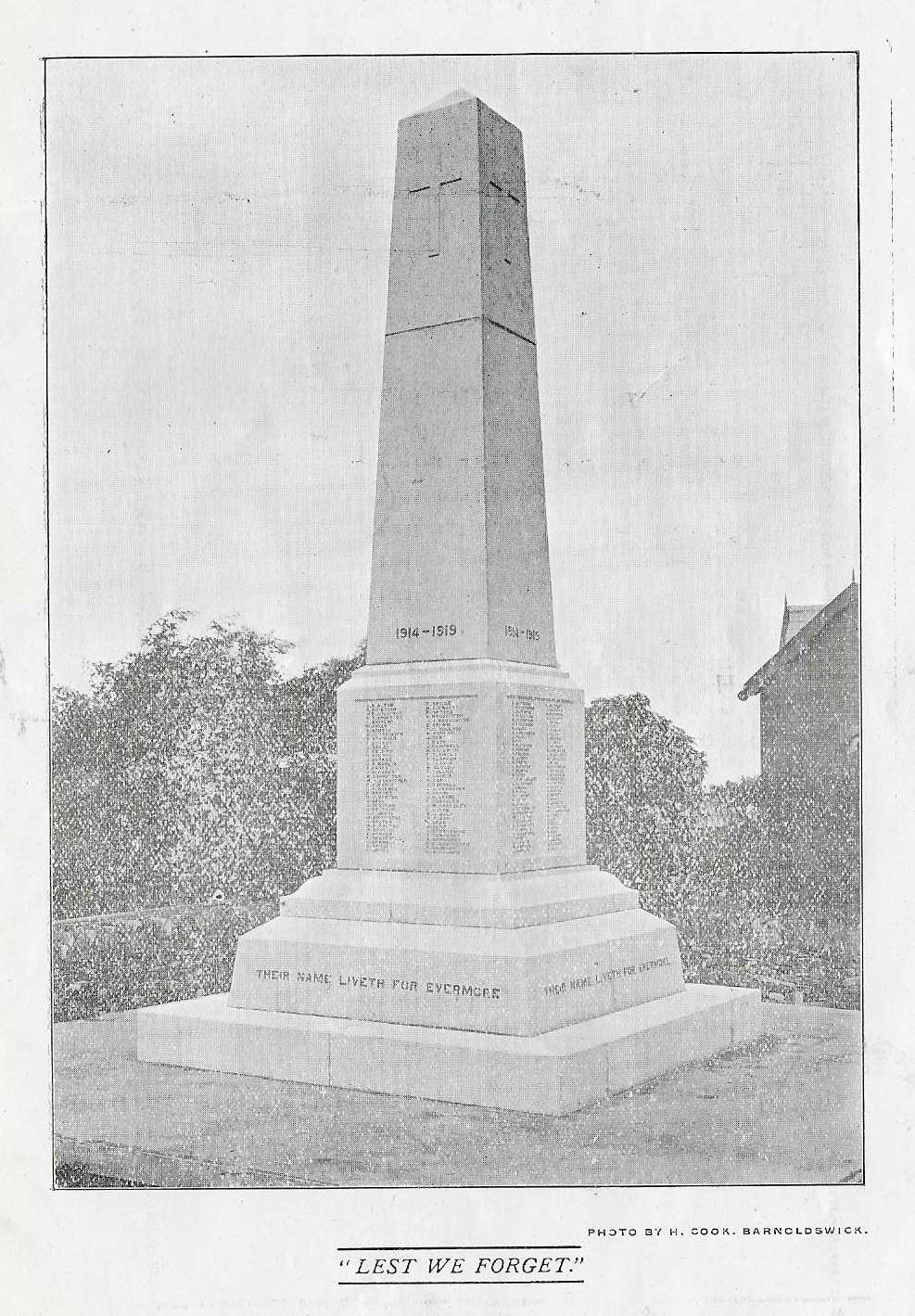

A HUNDRED years ago a small Craven town remembered those who had perished in that greatest of all conflicts the First World War. The Cenotaph, situated high above Barnoldswick, was unveiled by Mrs Elizabeth Anne Sutcliffe.

She had every right to be present as guest of honour: she had lost three of her five sons in the war. The deaths of 282 men from the town and surrounding areas were recorded there.

The programme of the events from that momentous day has been dutifully kept in the archives of Barnoldswick History Society, and yet no-one today could capture the emotion and the solemnity of the occasion.

The Craven Herald reported at the time: ‘At well nigh the highest point in the district stands the Barnoldswick War Memorial, a bold shaft of granite rising from a bed of flowers and encased within shrub-grown embankments and a sense of unusual impressiveness by Mrs Elizabeth Anne Sutcliffe…

The memorial stands in Letcliffe Park situated at an altitude from which one looks down almost sheer upon the roofs and bristling chimney stacks of the town. Nearly the whole of Upper Craven lies like an open book beneath the eye. Ingleborough pops up in the north-west, Rye-Loaf Hill, Malham Cove and Marton Scar are easily picked out, Gledstone describes a tiny crescent in the heart of a pretty woodland, the Rylstone obelisk is a clear speck on the dark Wharfedale Hills and at the other end of this loosely flung arc-line rises Skipton’s tallest factory chimney.

On Saturday one had little opportunity of exploring the park itself for the unveiling ceremony was attended by three or four thousand people who covered much of the available ground space.’ The reporter has captured the beauty and the majesty of the space, and yet he could only see a small fraction of the crowd. He had to move to one side. It was only ‘then that one caught sight of the vast concourse [or crowd] that stretched solidly backwards and upwards. The bank of faces was broken only by a war tank standing in grim irony on the hillside’.

‘The human voice sounded faint on this windswept height, and only those at the inner edge of the crowd could follow the ceremony from the announcements made within the low-lying enclosure. The few punctuations of bugle note, brass band and orchestral music were the guidance on which the rest had to rely’.

The Herald continued:, ‘the ensuing prayer, thinned in volume by the opposition of the wind which blew freshly over this high escarpment of the mid-Pennines, reached the mausoleum only at the whim of the breeze, and then but faintly’.

The formal handing over of the Cenotaph to Barnoldswick’s town council was ‘as if an alien hand’ had interrupted a service ‘charged with the twin senses of obligation and sorrowful pride’, but the journalist conceded you would need ‘an acute sense of values’ to detect the subtle change in the tone of the events. Perhaps the headline summed it up: ‘a deeply moving ceremony’, and yet there is an inescapable feeling that viewed from above we humans were dwarfed by the majesty of nature’s own spectacular display.

The Cenotaph itself was in the shape of an obelisk and had been built from light Shap granite which had been quarried in Westmorland. It had been designed by the council’s engineer and surveyor Wilkinson Ellis. The word ‘cenotaph’ is of Greek origin and means an empty tomb or monument erected to commemorate a person or group of people whose remains are buried elsewhere.

Perhaps the most well known is the Cenotaph in Whitehall in London which was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens who was one of the leading architects of his day. In a strange link with Barnoldswick, he was also the architect of Gledstone Hall at West Marton, a project which placed severe financial demands on its owner, local industrialist Sir Amos Nelson.

The First World War tank had been removed from the top of the gentle hill many years ago. In its place a metal plaque has been mounted on a circular plinth giving the distances to, and heights of, key locations in the surrounding countryside. Skipton’s tallest chimney can no longer be seen, but the view is much the same. Ingleborough is almost twenty miles away, Whernside twenty-four miles and Pen-y-Ghent just seventeen miles. Visitors to the area will not be disappointed. The original site of the Cenotaph can be viewed lower down the slope.

In 1983 it was moved to its present location on the corner of Fernlea Avenue and Wellhouse Road (by the Co-op supermarket car park). Some ten years ago there was talk of moving the Cenotaph to a new location in the memorial gardens on Kelbrook Road. The move was considered too expensive at the time. The caption to a photograph in the unveiling programme from 1923 read ‘Lest we forget’: it is harder to forget in the centre of our town. With hindsight it is best that the Cenotaph remained where it is: in the heart of our community.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here